North Vancouver conservationists say they’re upset that local municipalities are continuing to spray a toxic herbicide to control invasive species like Japanese knotweed and hogweed.

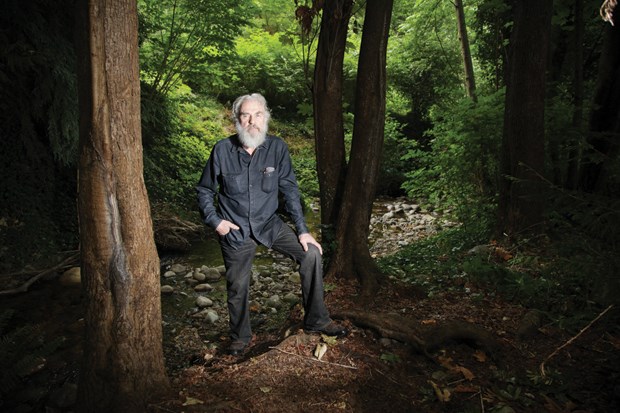

Kevin Bell, a local naturalist who worked at the Lynn Canyon Ecology Centre for many years, said he’s upset with a plan by the District of North Vancouver to spray the herbicide glyphosate (also known by the trade name Round Up) near local stream banks, wildlife areas and near parks where children play and pick berries this summer.

Bell said he’s especially concerned about plans to spray the chemical near areas like MacKay, Hastings and McCartney creeks as it can be harmful to aquatic life.

“It shouldn’t be used,” he said.

Approximately 200 knotweed sites in the District’s parks and boulevards will be treated this year, according to DNV spokesperson Jeanine Bratina.

“We will be treating the knotweed with glyphosate mostly by injecting the larger stems and spraying the smaller stems under one centimetre with a hand sprayer,” explained Bratina, adding the district follows provincial pest control regulations and does not treat knotweed located within one metre of the high watermark of streams.

The debate about using the herbicide is a perennial one on the North Shore. Under the Provincial Weed Control Act landowners are legally required to manage invasive species on their property.

Local governments that generally eschew use of toxic herbicides have in recent years returned to spraying the chemical in attempts to control invasive weeds like Japanese knotweed and giant hogweed, non-native plants that the district says wreak ecological chaos on the native flora and crowd out more beneficial plants.

One of the reasons the plant is difficult to eradicate is that it spreads underground through thick root rhizomes. According to the district’s invasive plant management strategy, for this reason, digging out the plants hasn’t been effective in controlling them.

But Bell said he doesn’t believe that. “It costs more money to do it manually,” he said. “Using herbicide is cheap and dirty and that’s what they like. It’s a lot of ecological spin.”

West Vancouver has banned glyphosate spraying, instead opting for repeated doses of herbicide done by stem injection — a method the municipality says is successful at controlling the spread of the tenacious weeds. But despite using 500 times more herbicide than spraying, stem injection is far less effective because knotweed needs “a slow death” and the product needs a chance to make it down to the root of the plant, according to the Invasive Species Council of Metro Vancouver.

The City of North Vancouver, meanwhile, uses a combination of treatments to kill knotweed. In some cases, small stems are treated with glyphosate and another herbicide called Milestone, using a hand sprayer within 10 centimetres of the stem.

The city says while it complies with the provincial regulations for protecting ecological habitats, the no-spray zones along the creeks have become infested with knotweed.

In areas that have been treated with herbicide, the city appears to be winning the invasive species war in that it’s been able to reduce the number of sites being treated by 81 and 86 per cent for knotweed and hogweed respectively, with Mosquito Creek Park being its model success story.

One special concern that crops up annually is the spraying of glyphosate in parks where children play and near blackberry bushes where people pick fruit.

While manufacturers say the chemical is safe, not everyone is convinced. Some studies have pointed to the herbicide as relatively benign. But some of those studies were funded by the chemical companies that make glyphosate, said Bell.

The World Health Organization recently designated the chemical “probably carcinogenic” to humans. Long-term effects of the chemical aren’t well known, said Bell.

Additionally, signs the municipality puts up to warn people that areas have been sprayed with the chemical are usually small and inadequate. “The signage is pathetic,” he said.

During one session of spraying at Deep Cove, “they put up one sign facing away from people…so the kids were playing in this stuff.”

North Vancouver resident Janice Wilson said the signage was poor in Panorama Park where pesticide spraying for knotweed was conducted on June 30, and not visible from the beach.

“Children were seen playing on the sprayed rocks later in the day,” said Wilson in a letter to the editor.

Another district resident, Elise Roberts, agrees that herbicide spraying should not be done during blackberry season. “What 10-year-old is going to read and understand a sign where berries are going to be sprayed?” asked Roberts.

The district said it relies on Health Canada’s Pest Management Regulatory Agency and the province’s Integrated Pest Management Act to determine which pesticides are safe for use in public areas.

Between now and September the district will be actively exterminating knotweed and hogweed and has provided a map of the treatment sites on its website. All of the parks where invasive species are being treated have signs at major entrances, while all patches have signage adjacent to them, said the district.