For 16 glorious years we were together.

From Troll’s to Honey Doughnuts to the water’s edge to the mountain’s shadows the North Shore was one big, broad, borderless municipality.

And then, not so much.

As we anticipate the collective reign of our newly elected mayoralty triumvirate of Mary-Ann Booth, Mike Little and Linda Buchanan, we wanted to look back at the diverse group of early 20th century white men – some with mustaches and a few rugged individualists without – who crafted the bylaws and scratched the zigzagging borders that continue to confine our residents and confound our tourists.

The Phibbs Exchange of Influence

Today, “Phibbs” is something we say when we’re worried the lasagna is going to get overcooked, as in: “I’m still stuck at Phibbs, could you make sure to turn off the oven?”

But in the 1800s Charles Phibbs was one of the most notorious names in Sligo, Ireland.

Phibbs – the one who didn’t become the North Shore’s first mayor – was known for his huge tracks of land and a sensitivity to the plight of others that could be measured in nanometres. Phibbs raised rents during a depression, took the good bog for himself and left his tenants to “dig for peat in a wet and useless bog,” according to historian Einion Thomas’ account: From Sligo to Wales – the Flight of Sir Charles Phibbs.

His son, yet another Charles Phibbs, was viewed as “the chief British sympathizer in the area, a situation that he seems at first to have relished,” Thomas writes.

However, some of that relish may have slipped off the hot dog in 1922 when a mock grave was dug in front of Phibbs’ house, complete with a mocking epitaph:

Here lies the remains of Charles Phibbs

who died with a ball of lead in his ribs.

His tenants are all aggrieved at as quick he went,

for he went of a sudden without lifting the rent.

In an account of his great uncle’s life, Fred Thompson writes that Charles Phibbs the mayor was born in Sligo in 1855 but that “little is known” about those early days.

Phibbs himself left Ireland while in his 20s, swayed by “propaganda that was spread all over Ireland telling of the wonderful opportunities for young men immigrating to Canada,” Thompson writes.

After arriving in Halifax in 1882, it took Phibbs four years to reach B.C.

Soldiers and fortune

With two teams of oxen and a pair of wagons, Phibbs and his longtime friend and business partner Fred Thompson were homesteading in northern Manitoba on the suggestion of retired major Charles Arkoll Boulton.

It’s where Phibbs might have stayed but rebellion was fomenting and Boulton soon came calling.

The Plains’ tribes saw their land vanishing and their food growing scarce amid the extension of the railway and the near extinction of the bison. Under those dire conditions the tribes formed an alliance with the Metis people who saw their life as fur traders disappearing. By 1884, Louis Riel rose from what one historian dubbed: “this cauldron of discontent.”

Boulton, a veteran of Gibraltar, Malta, and Montreal, recruited a militia including Phibbs and Thompson with the aim of putting down the rebellion.

Both men fought at the Battle of Fish Creek. Phibbs made it through unscathed. Thompson was shot in the shoulder, “but was able to extract it himself,” Thompson blandly writes.

If he hadn’t been shot, or perhaps if John A. Macdonald had been more averse to the starvation of the tribes, the North Shore’s history would have been altered.

There’s a gap in the history at this point, but it seems likely the friends used Thompson’s $500 grant to buy their dairy ranch on the east bank of Seymour Creek, the land that would become the Phibbs Exchange.

They settled down just as Vancouver was incorporated, in the age when real estate investors and local governments were as intertwined as the double helix in DNA.

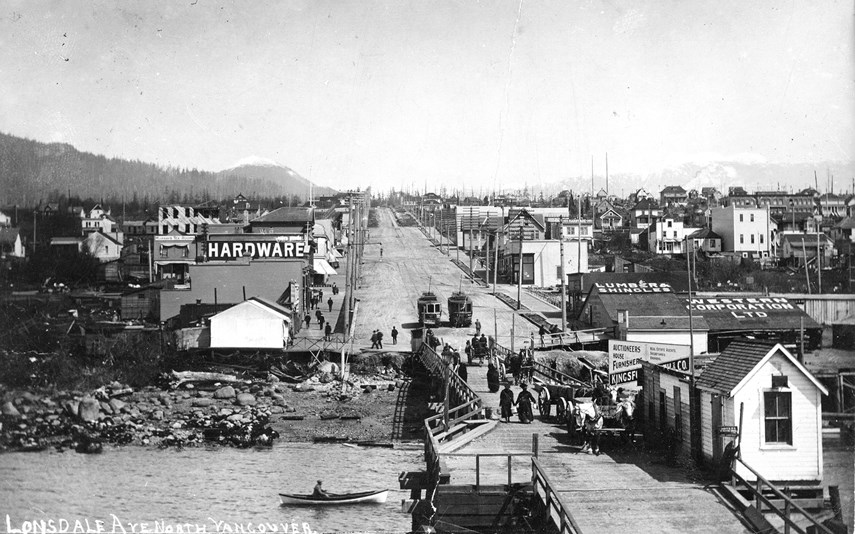

“Property owners, most of whom had invested in land but did not actually live on the North Shore, had decided the previous winter that the time had come to form a municipality,” Daniel Francis writes in his book Where Mountains Meet the Sea. “They were encouraged by the creation of Vancouver in 1886 and the spurt of growth that the city subsequently experienced. Property values soared amid a frenzy of building and speculation. Why could not the same expansion occur on the north side of the inlet?”

The house always wins in early elections

“ . . . she threw up her job sooner than teach immoral geography.”

– Rudyard Kipling, The Village That Voted The Earth Was Flat

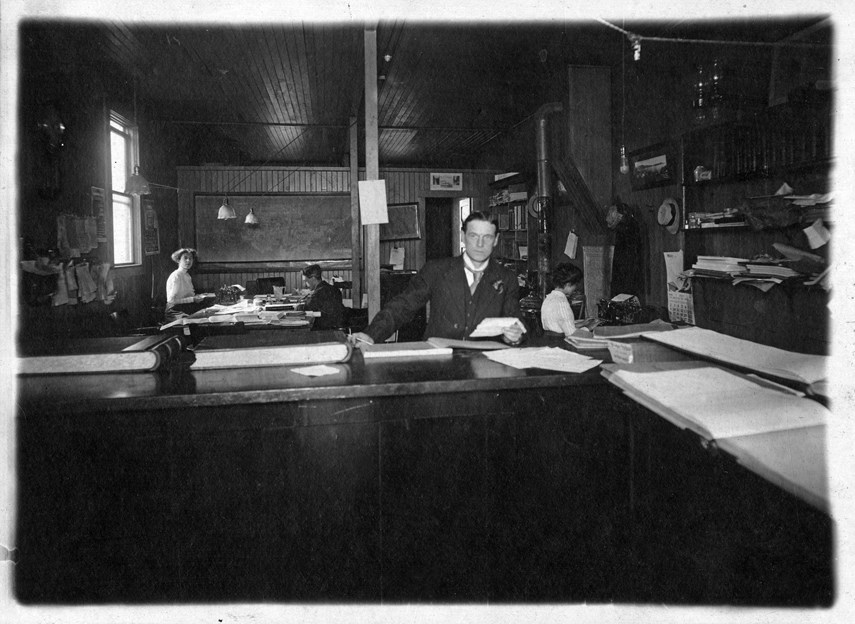

On Aug. 22, 1891, North Vancouver’s first election was held at a converted saloon on what is now Chesterfield Avenue. Tom Turner’s house, Francis writes, is: “the birthplace of North Vancouver.”

And from the moment of birth, voter turnout was something of a problem.

While eligible, Rudyard Kipling, perhaps because his suspicions about the merits of democracy or simply because he was out of town, didn’t cast a ballot.

Phibbs began his service as mayor with Thompson and Tom Turner – conceivably because it was Turner’s house and no one wanted to seem rude – as councillors.

With the exception of Moodyville and Indigenous reserves which belonged to the federal government, Phibbs essentially had the run of the place as reeve, and he made it worth his while.

By December of 1891, a newspaper report notes, Phibbs “had $30 per acre knocked off his assessment,” bringing the assessment on the ranch down to a more comfortable $100 an acre.

The big question facing council, then and now, was transportation.

Land promoter James Cooper Keith underwrote a loan to build Keith Road, although Francis notes, “progress was slow.”

However, overall progress was likely accelerated by John Mahon’s North Vancouver Land and Improvement Company. Mahon, in the fashion of bossy big brothers since time immemorial, sent his younger brother on an errand.

Charged with guarding his brother’s investment, Edward Mahon donated the land that became Central Lonsdale’s first church and devised the notion of a single boulevard circling the city ringed by parks and gardens. While the trail looks decidedly different today, the Green Necklace cycling trail is an extension of Mahon’s idea.

Phibbs was re-elected in 1892, and one senses he probably enjoyed an advantage due to his experience and the fact the election was held at his house.

A News-Advertiser article, dutifully transcribed by the late, local historian Dick Lazenby, recalls Phibbs along with Keith, who would become the district’s next mayor, and several councillors looking at the North Shore from a steamer, thinking about what their planned road would look like.

“All present expressed satisfaction at the location of the road and the great boon it will be to settlers when completed,” the reporter concluded.

In his last meeting as Reeve, Phibbs collected $63 for expenses for having endured 21 council meetings.

Even Kealy and the business of government

While some complain commerce invaded municipal politics, history suggests it may have been the other way around because before there was any government on the North Shore, there was business. Unfettered by bylaw or bureaucracy, Moody’s Mill paid $1.50 a day (or 75 cents plus room and board) to an international work force who shipped timber all over the world.

As early as 1865 church services were led by a clergyman with a name escaped from a Dickens novel: Reverend Ebeneezer Robson. A library and museum followed and a school opened in 1870 (although classes sometimes let out early on days when sawmill smoke snuck under the door.) There was also the region’s first local newspaper: The Moodyville Tickler.

“The more you paid for your obituary, the more glowing it became,” historian Chuck Davis notes in his History of Metropolitan Vancouver.

Lit by dogfish oil lamps, Moodyville was almost – almost – the epicentre of Burrard Inlet. But Francis cites 1885 as a watershed year when Canadian Pacific Railroad’s general manager chose the townsite of Granville over Moodyville as the railway’s terminus.

Back then, the region was carved into neighbourhoods with great, evocative names like The Rookeries, Kanaka Row, Maiden Lane, Knob Hill, and – in the sawdust landing where the road dipped into the water – The Spit.

“There was nothing much to do in those days, so for something to amuse ourselves we used to watch the logs come down a long runway where Lonsdale Avenue is now,” recalls John Henry Scales, who lived in Moodyville in the early 1870s.

The best entertainment was when two logs collided, Scales recounts: “both split into pieces, and huge splinters flew in all directions. It was a wonderful sight; not likely to happen again. ...”

Although if you were entertained by sudden, impactful fractures, the best was yet to come.

Splitsville

The de-amalgamation process began in 1907 as the most lucrative bit of District of North Vancouver real estate rechristened itself, creatively enough, the City of North Vancouver.

“(Ratepayers in the commercial core) thought it would be advantageous to create a smaller, more concentrated municipality with less responsibility for providing services to the large, but as yet sparsely populated, outlying area,” Francis writes. “There was really no one to speak for the interests of the fewer residents who lived beyond the central core.”

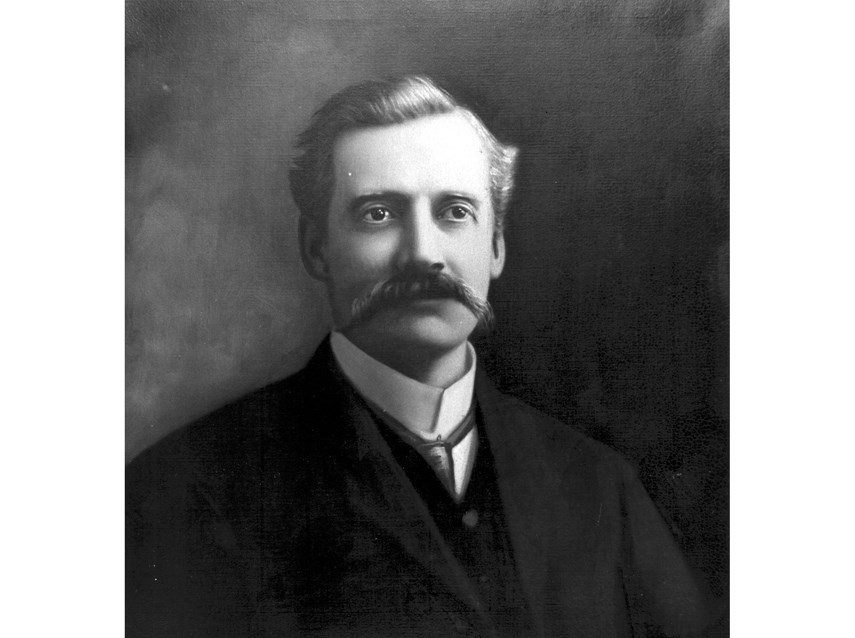

Serving from 1905 to 1907, Arnold Kealy was the last true mayor of the North Shore. He was also the first mayor of the City of North Vancouver.

Kealy couldn’t continue as district mayor, he said, explaining the “financial remunerations are not sufficient to recompense me for the work that I must do.”

With a pleasing bass voice that earned him “amateur choral and stag opportunities,” and an old-growth mustache big enough to smuggle a derringer, Kealy took over as city mayor and quickly bumped his salary from $600 to $1,000. (This was at a time when future mayor George Washington Vance was selling “almost cleared” lots for $350, advertising them with the phrase: “The Bridge Is Coming Sure.”)

To hear Kealy tell it, the city was getting a bargain.

“I believe that if I am elected to the office of mayor that I will put our little city upon such a solid financial basis that for all times to come we need never to fear a financial crisis,” he claims in a 1907 Province article reproduced by Lazenby.

Kealy so loved North Vancouver he gave his son the middle name Norvan. He saw the city’s destiny as not just as big as its neighbour across the inlet, but bigger.

“At present North Vancouver is one-third the size of Vancouver, but it will be five times the size. Its natural wealth cannot be got over. There are wonderful possibilities in the valleys. ... After a city has reached a population of fifty thousand it grows by leaps and bounds.”

But while the city got Kealy, the district didn’t seem to get much.

While the city paid “some of the district’s outstanding liabilities,” the district lost its ferry terminal, road making equipment, “even the cemetery,” Davis notes.

The city even took the district’s municipal hall at 333 Chesterfield Ave. as their own, Davis notes.

But while the city was concentrated and business oriented, by at least one account the District of North Vancouver residents were free to carve out a Huckleberry Finn-like existence.

“You fished without a licence and none was needed to hunt, light a fire or pan for gold. In fact, no ‘Don’ts,’” Lynn Valley pioneer Walter Draycott wrote in his diary. Truly, the ‘Good Old Days!’”

In contrast, the city took several steps to alleviate the spread of fun through North Vancouver by the 1920s. Mayor G.H. Morden was the first official with the courage to bring the hammer down on hucksters and hippodromes, signing off on a bylaw that demanded a $1,000 bond with the city to guard against circus damage. Morden also signed a bylaw that authorized the city to fine parents a maximum of $5 in the event their child (which included anyone “actually or apparently” under the age of 16) was on the street after 9 p.m. Incidentally, the fines were some 20 times heftier for any farmer who failed to provide adequate ventilation and natural daylight for their goats.

While Kealy’s mustache can be overlooked as something expected for the times, his racism seemed excessive, even by early 20th century white guy standards.

In articles published only one month after racist rioters swept through Vancouver’s Chinatown, Kealy celebrated his role in the Asiatic Exclusion League.

“There is no question,” Kealy is quoted as saying in a 1907 Province article reproduced by Lazenby, “but that this should be kept a white man’s country, and only a white man’s country.”

Kealy was also known as a central figure in a performance by the Royal Norvan Minstrels, which is every bit as stomach churning as it sounds, described in The World newspaper as: “familiar features behind black physiognomies.”

Kealy did show a strong moral backbone on other issues, however, such as when it was suggested Vancouver baseball teams might play nine innings in North Vancouver on a Sunday.

“What do they take us for? Do they think that North Vancouver is to be made a dumping ground for what Vancouver will not stand for? There will be no Sunday baseball in North Vancouver. You can rest assured of that,” he declared.

On municipal issues, Kealy suggested there were three great questions facing the city: the ferry, the railway, and “the bridge question.”

One bridge, gently used. Motivated seller

In 1907, to celebrate the incorporation of the City of North Vancouver, the new municipality held an essay contest.

The winner, R. McLean, dubbed the city, “a county of sunshine and mellowness.”

Noting a bridge that will form a “permanent binding” with Vancouver, McLean underscored the opportunity inherent in the municipality.

“Land values, while increasing steadily and yielding good returns, are moderate and within reach of people of small means,” McLean wrote. “Brisk building operations are in progress everywhere, and a vacant house is a thing unknown.”

“This is only the beginning,” McLean concludes. “The tide has not nearly reached its height.”

The original Second Narrows crossing opened on Nov. 7, 1925. In less than five years, McLean’s words took on a terrible irony.

To save money, the engineers placed the bridge too close to the shallow side of the Narrows. “Vessels routinely struck the piers, putting the crossing out of commission,” Francis writes.

Ultimately, a log barge got caught between a high tide and a low bridge and stuck.

The crossing wheezed, wobbled and collapsed. And with it went North Vancouver.

The bridge had been financed by bond sales, which, Francis notes, placed an “onerous burden,” on local governments.

In successive years, the district collected less than 40 per cent of outstanding property taxes while cutting back municipal services by 68 per cent, Francis notes.

After having one mayor, then two mayors, the two North Vancouvers were about to have no mayors at all.

In Part 2 we examine the aftermath of the bridge collapse and a few of the political machinations that led to the creation of West Vancouver. Tune in next week for more mayors and more mustaches.