It was emotion in its rawest form, unmistakeable to a gymnasium packed full of teenaged basketball players, fans, officials and friends.

The Handsworth senior girls had just won the 2009 provincial AAA championship and Jamie Keast stood in front of the crowd ready to hand out one of the many awards given on that day.

“The Quinn Keast Most Complete Player award goes to, from the Handsworth Royals, Bethan Chalke!”

Before she could pick herself up off the floor where she was sitting with her teammates, Chalke was already covered in tears. By the time she reached Jamie, both young women were quivering messes that melted into each other in an embrace that caught every breath in the crowded Capilano Sportsplex.

Three years younger than Quinn Keast, Chalke had watched him from afar in the Handsworth gymnasium when she first arrived at high school. Quinn was a hard-working cornerstone on the school’s dominant senior boys basketball team as well as a humble rock star in the hallways.

“I was one of those anonymous faces in the gym at high school boys basketball games,” says Chalke. “He certainly didn’t know who I was but I definitely, definitely knew who he was. You can’t look at somebody like that and not be inspired. Still today he inspires me.”

Quinn’s life ended in the early hours of June 11, 2006, when he was hit by a transit bus while on his way to an after-grad party in downtown Vancouver. Three years later Bethan Chalke received a simple award named in Quinn’s honour. It remains one of the highlights of her life.

“It was just the most wonderful, humbling thing I could possibly think of,” she says. “To be mentioned in the same breath as Quinn was a huge honour.”

Chalke was the first female athlete to receive the Most Complete Player Award from the Quinn Keast Foundation. Many more awards have followed, as have numerous other initiatives – scholarships, courts, tournaments – as the memory of a young man has grown into a legacy that has touched thousands.

A senseless accident took away a beloved athlete, shook a tight-knit community and decimated a family. Ten years later the loss is still felt every day, but something else is there too. There’s a basketball empire that seemingly grows stronger every day, carrying with it a legion of young boys and girls who are learning what it really means to live life with no regrets.

• • •

Jamie and Quinn Keast were the “attached at the hip” kind of twins, the ones who did everything together, had the same friends, even the same thoughts. When they were young, their parents would put them into separate cribs in their shared North Vancouver bedroom only to find them in the morning mysteriously sleeping side by side. When they got older they were in separate rooms beside each other but begged their parents to knock a hole in the wall so that they could build a tunnel. When that plan was shot down, they took to slipping notes under each other’s doors, letters to keep each other updated on the happenings on the other side of the wall.

Jamie and Quinn stayed together even when it wasn’t convenient, like when Quinn joined a boys soccer club. Jamie was the only girl in the league. The Keast kids didn’t care.

They played together as long as they could, and when they couldn’t do that anymore they took their powerful sports engines onto new teams.

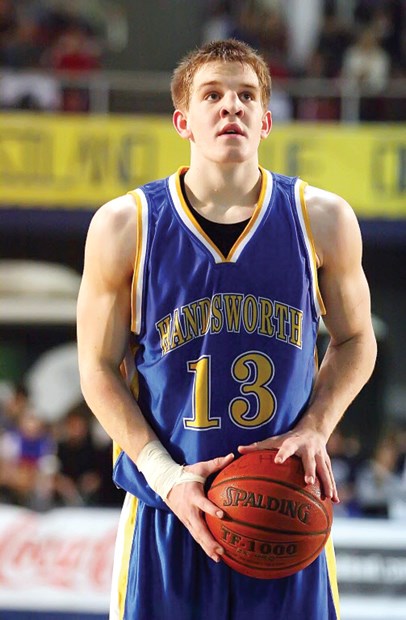

Quinn was good enough at basketball to make a provincial team. After his Handsworth senior team failed to win a provincial title in 2005, he famously vowed to take 100,000 shots over the summer so that he’d be ready to push the Royals over the top in 2006. And that’s just what he did.

Fighting through injuries and playing on a team loaded with talented players – including towering centre Rob Sacré, who is now a member of the Los Angeles Lakers – Quinn still dominated the provincial championship final, earning player of the game honours after scoring 17 points and grabbing 16 rebounds in an 82-65 win over the Kitsilano Blue Demons in front of 3,000 fans at the PNE Agrodome.

Quinn was injured in the semifinals and his teammates were worried he might not be able to even play in the final.

“He had a bad fall, wrist was banged up. He went to physio,” remembers Quinn’s best friend Scott Leigh, who also starred on that Royals team. “I go in and he is bandaged up like a mummy. His wrists are covered, he’s got no mobility. I’m looking at Quinn going, ‘Man, we got a game today. Are you feeling OK?’ By the time we get to the game it’s as if it never happened and he has one of the best games of his life. … It’s a classic story of Quinn – no quit, and just absolute determination. No matter what he did he was going to come through.”

Jeff McCutcheon, another close friend, watched the game from the stands with the rest of the howling Handsworth fans.

“He was a beast,” he says of Quinn. “We were in Grade 12, like 17 years old, and he had biceps the size of the basketball. He wasn’t the biggest player, he wasn’t the fastest, he wasn’t the quickest but he just had the biggest heart.”

Three months later, Quinn was gone.

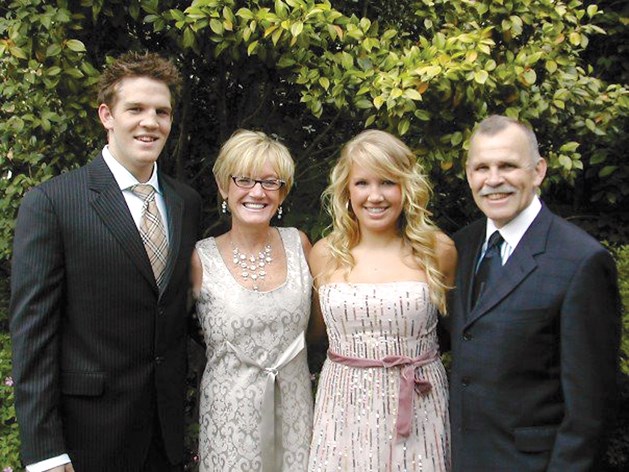

The accident occurred on grad night. The Keasts took a family photo at home in their formal wear and then headed to a ceremony in Coal Harbour. They all danced together, and Quinn told his mother it was the best night of his life.

An after-party was being held at a restaurant a few blocks away. Jamie arrived first, but she didn’t want to go in until Quinn showed up. He never did.

Both Jamie and her father, Tom, spoke at Quinn’s memorial, held in the same Capilano Sportsplex gymnasium where so many epic basketball stories have been written over the years. Neither, however, can recall much of anything about the service or what was said.

“I have a video of it that I’ve never watched,” says Tom. “I’m not sure I could.” He sang with his choir, and said a few words.

Jamie drew a laugh with a story about Quinn asking her for fashion advice about whether or not he should try out a bold new outfit. He respected her opinion enough to ask for it, but not enough to listen to it.

“It looked terrible. It was like white on white,” says Jamie. “I was like, ‘No, you cannot do that.’ And then he just wore it anyway.”

There wasn’t much laughter after that though. In an instant, Jamie had become an only child – a sensation she’d never known, even in the womb. Extended family members were assigned to Jamie, Tom, and Jan Keast, Quinn’s mother, to make sure that they made it through the following days in one piece. In the years to come, Jan – who says she had an “old-soul relationship” with Quinn – was nearly lost to grief.

“My mom was in immense shock,” says Jamie. “Her body was in physical shock.”

That summer the three remaining Keasts took a hike on Grouse Mountain where they held each other in a huge hug, committing to each other that they would all get through it together.

“I wanted to believe we were going to do it,” says Jamie. “(But) our family was never the same. … I just watched our whole family sort of fall apart.”

Jan and Tom divorced five years after Quinn’s death. Both say they dealt with grief and loss in very different ways, and that sent them in different directions.

Jan’s grief was compounded by health problems that began before Quinn’s death but grew after it, putting her into the hospital frequently and requiring a string of surgeries.

“I struggled a lot after we lost Quinn,” says Jan. “I really couldn’t come to terms with it. … I don’t think Tom thought I would ever survive it. I didn’t either, to be honest.”

Jamie often wonders what the family would look like if the accident never happened.

“It changed so many dynamics in my life and in my parents’ lives,” she says. “It’s something that I’d never considered or wanted to consider. It changed everything.”

• • •

While the family was immediately shattered by the accident, a powerful force soon began to build the net that would eventually help lift the Keasts back up. It was Quinn – or rather, the memory of Quinn, who had generated an enormous amount of goodwill in his short time on earth. Coaches, friends, classmates, even opponents – everyone raved about the young man who competed with honour and passion.

“All I could think about was making sure that his legacy lived on as long as possible,” says Scott Leigh.

The message quickly spread, and money started coming in. In the first while there wasn’t an official charity, no tax receipts were issued, but donors didn’t care. The amount donated in a very short time period was staggering: more than $100,000.

That summer Digby Leigh (Scott’s dad), Leslie Sacré and Blair Shier, three family friends who were all deeply involved with Handsworth basketball, established, along with the family, the Quinn Keast Foundation.

Scholarships are the backbone of the foundation – thousands of dollars every year given to players at local, regional and provincial tournaments, athletes chosen not just for being the most talented but also the hardest-working, the most coachable, the best teammate.

There have been numerous events as well, starting just six months after Quinn’s death with a pair of exhibition high school basketball games held at Capilano University. More than 1,500 fans and friends attended the games, raising more than $10,000 for the foundation.

An army of shooters young and old mobilized across several locations to attempt, in one day, to shoot the famous 100,000 shots Quinn had vowed to shoot. They shot 169,000, and on the same day collected more than 1,000 pairs of shoes that were shipped to South Africa.

Memorials were built, including full, high-quality outdoor basketball courts placed at three elementary schools and emblazoned with a giant Q. Wristbands, murals, a stained glass window – tributes continued to pop up across North Vancouver and beyond. It was all very touching for the family, although Jamie admits that the constant reminders got to be overwhelming at times.

“For me there were times when I wanted to take a step back. It was like, ‘Oh this is a lot,’” she says. “It was a very public situation. That was super hard because I couldn’t go anywhere without having questions, or someone coming up to me. That was one of the hardest things for me – I just wanted to go somewhere and have my own identity and not just be Quinn’s sister. As much as that’s what I’m most proud of in my life, I needed to form my own identity outside of that if I was going to continue on in a healthy environment.”

Jamie has done that now. She’s on the board of the Quinn Keast Foundation and still heavily involved in its operations, but just this month she graduated from the University of the Fraser Valley with a teaching degree. She’s already grabbed a position as a substitute teacher in Langley and would love to come back to North Vancouver as a full-time teacher.

Jamie and Tom Keast get set to host dozens of friends and family members at a barbecue celebrating the life and mantra of Quinn Keast. photo by Paul McGrath, North Shore News

Jamie and Tom Keast get set to host dozens of friends and family members at a barbecue celebrating the life and mantra of Quinn Keast. photo by Paul McGrath, North Shore News

In the last few years the foundation has pivoted away from Quinn the man and started focusing on his message.

In popular culture the term “no regrets” has become somewhat of a cliché, another YOLO call to justify thrill seeking. But for Quinn Keast it was a very real, thoughtful, tangible mantra. He kept a diary the last years of his life, and before his Grade 12 year vowed to live life to the fullest, work hard at everything he did and love lots. If you do everything in your power to prepare yourself for life’s challenges – and make sure those around you know they are loved – then you will have no regrets, not matter what the outcome.

Those who loved Quinn, and were loved by him, have taken up his call. On the 10th anniversary of his death more than 60 family and friends gathered for a barbecue at John Lawson Park, all still drawn together by bonds forged by Quinn. It was a chilly evening so there were a lot of sweaters and long pants – not shorts and tank tops – so it wasn’t readily apparent that a good number of those in attendance had the words “No Regrets” tattooed somewhere on their bodies.

“It’s how I live my life and will continue to live my life every day,” says Scott Leigh. “I feel lucky that I was able to actually appreciate the message that Quinn was trying to deliver.”

Bethan Chalke says that it’s rare for a day to go by without her thinking about Quinn. As she recalls the night she won an award named after Quinn, she’s wearing her own No Regrets wrist band.

“It gives me goosebumps!” she says. “(No Regrets) has got such a warm meaning for me and I think for a lot of people that knew Quinn. It really makes you stop and think. You don’t think, Oh, No Regrets, that old saying. You stop and you think, No, hold on. I’ve got to do this now! I don’t know if I have a tomorrow. It’s definitely really powerful for me.”

If you searched a baby name registry for the North Shore, you’d likely find a bump in the use of the name Quinn in recent years. A basketball coach, an NBA player, a baseball coach, even the police officer who had never met the Keasts until he showed up on their doorstep to tell them that their son was gone – these are a few of the people who now have children named Quinn, or some similar sounding variation.

“He made an impact,” says Larry Donohoe, a staple on the North Shore sports scene who coached Quinn on the U16 provincial basketball team. Donohoe has handed out many Quinn Keast awards over the years, and his voice always catches when he begins to read the short bio telling the young players who Quinn was and what the award means.

“He stood for something and he worked hard,” he says. “When you coach, there’s kids that you remember. I don’t remember Quinn because he died. I remember him because he was such a great kid and I thoroughly enjoyed coaching him. You really felt like you had an impact with him.”

As he spoke, Donohoe was wearing a jacket emblazoned with the words No Regrets. For 21 years he was the director of the North Shore Invitational Tournament, a high-profile annual high school event. Last year it was renamed the No Regrets Basketball Tournament, with the Keast family and foundation throwing their full weight behind the event. The switch was a no-brainer, says Donohoe, and after just one year it’s evident it’s breathed new life into the tournament.

“It now stands for more,” he says. “It’s a work in progress, the No Regrets, but it’s turning into something special.”

That’s what the Keast family wants to hear.

“It’s the philosophy that’s going to carry on with us, not so much the mourning of a person,” says Tom. “Even though it’s my son.”

• • •

In North Vancouver’s Victoria Park there is a little sculpture tucked away in a quiet area. Named Enduring Love, the piece is the “creative outcome of a collaborative community art process inviting bereaved parents to express the love felt for children, lost from our sight but not from our hearts.”

It’s a calm, comforting, moving piece of work, but there’s no mistaking one distinctive feature – a hole right in the middle of it.

The Keast family is one of the many that knows what that hole feels like.

“I remember people saying it’s going to get easier,” says Jamie. “It doesn’t. Ever. … I think when I’m a parent one day I’ll understand more of what it’s like to be a parent and just face the fear of having a child that might not be around forever. We all want to think that we’re invincible and that’s not going to happen. … Our family knows that that’s not the case.”

The hole will never be filled, but the Keasts have found new joy in the foundation and the way that it is supported by the community.

“It was a saviour for me,” says Jamie of the work she did with the foundation. “It was sort of for me a light at the end of a tunnel that I didn’t know I was ever going to get to. … I think being able to spread his message, or joy, or love of the game – being able to do that, as opposed to doing nothing, helped me and I know it helped my parents. It was definitely a saving grace in a time that was terrible.”

Tom marvels at the number of people who have picked up Quinn’s cause in some small or large way – thousands of them.

“The community and the people in it have been fantastic for our family,” he says. “I can’t say enough about that. It’s selfless. It’s not that they’re doing it for any personal gain or anything else. I think that they believe that Quinn was a good kid and a kid that stood for something.”

Jan was just out of hospital on the night of the 10th anniversary and wasn’t able to make it to the barbecue. She still had a spiritual moment, however, sitting in the garden outside the recovery house she was staying at on the Sunshine Coast. Just as dusk was approaching she felt a presence, and turned to see a massive buck sitting on a nearby rock. It was a sign, she says, a message from Quinn.

“I’m ready now to carry on and to start back up my life,” she says. “Ten years is a long time. It just blows my mind that it’s been 10 years. It feels like yesterday. I grieved a lot and I’m willing to let it go. I feel like it’s time to start again.”

A huge part of that healing process has been watching the foundation grow.

“It gives me great pleasure to watch this, and start a new group of kids that are willing to do those things that took the extra work,” she says. “I think Quinn left a nice, lasting legacy for our community.”

She often drives by the memorial courts and sees young children playing. They never would have met Quinn, but some day they’ll learn why there’s a Q in the middle of the basketball court where they first picked up a ball and shot it through a hoop.

“It means a lot,” she says. “It means that his message carried on through the years. He was not the best at everything he did – I would never blow him up to that – but he had a sensitivity to him that made people really connect to him. … He played well, and I don’t mean expertly. He was a fair guy.”