If you want to ask a scientist how to save the world, maybe start by asking how so many cultures have survived this long.

Wade Davis, UBC anthropologist, author and National Geographic Society explorer-in-residence, is bringing that message to West Vancouver in a public lecture at Mulgrave School, Sept. 15.

“The thrust of my work as an anthropologist is really trying to make the world safe for human differences and for diversity. My mission at the (National) Geographic for 15 years was to really kind of change the way the world views and values culture,” he said. “We have a strong conviction storytellers can change the world.”

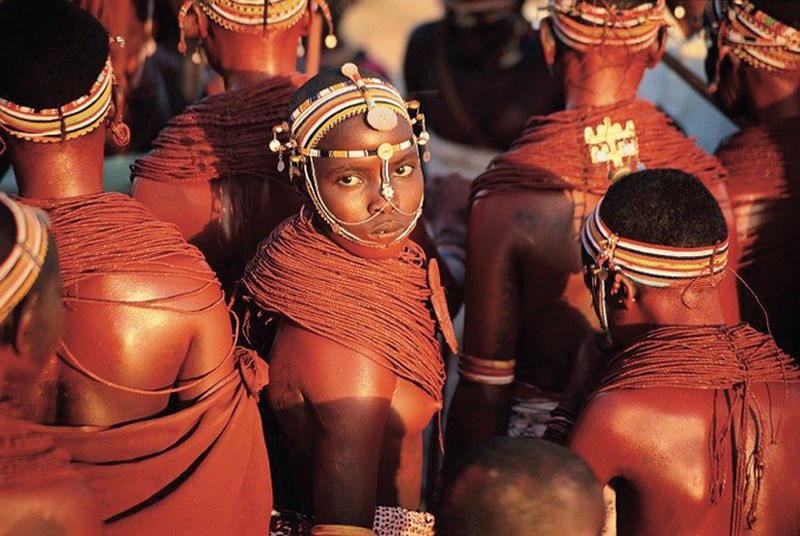

And so Davis will be telling some of the stories he’s collected living and doing ethnographic research among the indigenous people of more than 80 nations.

Among the stories most frequently recalled in his lectures: studying survival in the high Arctic; learning the origins of Voodoo in West Africa; sailing with the descendants of the Polynesian navigators who, without any navigational aids, colonized the most remote islands of the Pacific 1,000 years BCE; visiting an 800-year-old salt mine in the middle of the Sahara Desert to better understand Islam; and seeing how spiritual beliefs of the Amazon tribe known as the People of the Anaconda contribute directly to the way they manage their land and thrive.

The takeaway from these stories is an abiding respect and understanding of the “dazzling” ways indigenous people have formed their beliefs and adapted to the world around them.

“The other peoples of the world aren’t failed attempts at being modern or failed attempts at being new. Every culture is a unique answer to a fundamental question – what does it mean to be human and alive?” Davis said.

The subject of the Mulgrave talk dovetails nicely with the International Baccalaureate school’s Theory of Knowledge class, which challenges students to reflect on the nature of knowledge, and on “how we know what we claim to know.” Those students will be getting a private lecture from Davis earlier in the day.

“The great revelation of anthropology was that the world that you’re born into is just one model of reality, the consequence of one set of choices your cultural lineage made, however successfully,” Davis said. “The other peoples of the world remind us there are other ways of thinking, other ways of being, other ways of orienting yourself in social, physical, even spiritual space.”

But those ways of thinking, speaking and being, and the tremendous intrinsic value they hold are under critical threat, arguably more so than any particular ecosystem or branch of flora or fauna. To illustrate, Davis points to the “haunting statistic” that of the 7,000 languages spoken on Earth today, half aren’t being taught to children. Less than a third of one per cent of the population is still actively speaking these dying languages.

“As these languages disappear we are literally losing half of all humanity’s intellectual, spiritual, social, ecological knowledge, and this doesn’t have to happen,” he said. “We hear so much about the threat to endangered species but no biologist would dare suggest that half the species of the world were on the brink of extinction. And yet that most apocalyptic scenario in the realm of biological diversity scarcely approaches what we know to be the most optimistic scenario in the realm of cultural diversity.”

Some like to retort that a world where everyone speaks a common tongue would be a better place, but Davis isn’t having it.

“What a fine idea,” he said, sardonically. “But let’s make that language Haida. Let’s make it Inuktitut. Let’s make it Lakota… You suddenly begin to feel as a native speaker of English what it would be like to be enveloped in silence with no means to pass on the wisdom of your ancestry or anticipate the promise of your descendants.”

But as Davis points out, the disappearance of language and culture isn’t a naturally occurring phenomenon. It’s man-made. The eradication of indigenous cultures was fed, in part, by the wrong-headed thinking of 19th century anthropologists who tended to view other cultures on a hierarchy, always with their own culture at the top and varying degrees of savagery below.

Davis points to Europeans clashing with Australia’s aborigines as one of the worst examples.

Because they looked strange, had simple technology and – most offensive to the Victorian British – showed little interest in acquiring material goods, the British concluded they must be something less than human.

“As recently as the 1950s, ranchers had quotas on how many ‘Abbos’ they could shoot who trespassed upon their land,” Davis said.

What the colonists failed to understand was that the entire ethos of the people they so dehumanized was dedicated to continuing the rituals deemed necessary to keep the world exactly as it was at the time of creation.

In other cases, it’s forced assimilation by a dominant political or religious force, much like Canada instigated with Indian residential schools.

Here on the North Shore, the Squamish language has only seven fluent speakers left, a legacy of St. Paul’s Indian Residential School, which stood where St. Thomas Aquinas secondary now welcomes students.

Lastly, industrialization and resource extraction on traditional indigenous lands has forced people to abandon their traditional ways of living to scrape by in a cash economy, typically with a lower quality of life, Davis said.

“Too often, indigenous peoples are given a false choice of either poverty or industrial activity that compromises the thing they love most – their homelands,” Davis said.

But the good news is things are turning around, albeit slowly. Canada has mostly parted ways with the old pedagogy, learning to celebrate and encourage First Nations people fostering their own culture, Davis said. Recognizing Aboriginal land title and granting self-governance, as has been done in the case of Nunavut, have also been steps in the right direction.

And there is a movement afoot to revive Squamish language, including an immersion academy set up by local activist Khelsilem. It would be naïve to assume the Squamish people will give up speaking English and readopt their mother tongue as their main form of communication, Davis said, but there is great value in keeping the language alive.

“There’s an incredible moral and political and psychological power in even the efforts to maintain the language,” he said. “It’s not about isolating the Squamish people with their language and no access to modernity. It’s about how can they as a group of individuals embrace this realm of modernity, but critically.”

Much as other cultures change and adapt, so too must ours, and sooner rather than later if climate change has anything to do with it, Davis said. In many ways, we have the wind at our backs when it comes to progress.

“When I was a kid, just getting people to stop throwing garbage out of their car was a victory. Words like biodiversity and biosphere hadn’t been invented yet, and now they’re part of the vocabulary of schoolchildren,” he said. “In my lifetime, women have gone from the kitchen to the boardroom. People of colour from the slave ship to the White House, gay people from the closet to the altar. The information age has put the knowledge of the world literally at the fingertips of everybody with a device. We’re moving absolutely into a post-carbon energy economy.”

The two most important scientific achievements of humanity, in Davis’s mind, are the first images of the Earth taken from the Apollo spacecraft and the decoding of the human genome. Taken together, they underscore the message that we are one people sharing one habitat.

Despite the bleak misfortune being foisted on indigenous people in so many places, Davis still beams with optimism. Perhaps a bit like Scrooge waking up on Christmas Day to realize he still has time to mend his ways, we too have an opportunity. And the anthropologist’s best advice: listen to the voices of the thousands of other cultures while they’re still here and speaking.

“None of this is to be pessimistic or apocalyptic. On the contrary,” Davis said. “Every culture has something to say and each deserves to be heard.”

Wade Davis will speak on Sept. 15, 7-9 p.m. at Mulgrave’s Linda Hamer Theatre, 2330 Cypress Bowl Lane. Admission is free but attendees are asked to RSVP at info.mulgrave.com/wade-davis. Davis is also publishing two books this fall including Wade Davis Photography, a collection of his favourite photos from the last 15 years, and Cowboys of the Americas, a reflection on the relationship between humans and horses in traditional farming.