New Forms 13: Contemporary Art and Music until Sept. 15. Visit 2013.newformsfestival. com for information.

Synthetic sounds spread across the tranquil California commune.

The bloops, bleeps, and metallic hums had one meaning for the tie-dyed denizens of the late 1960s.

"All these hippies started crawling out of the bushes with these amazed looks, convinced that martians had landed," recalls Ramon Sender in the forthcoming documentary Buchla: California Maverick on a New Frontier.

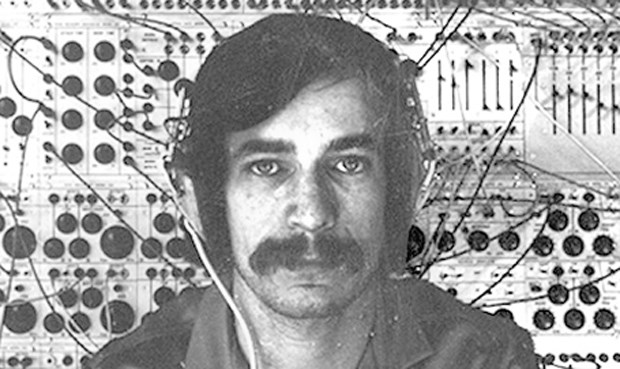

Perhaps the preeminent pioneer of electronic music, Donald Buchla has spent more than 50 years creating otherworldly music.

Responding to three questions over the phone, Buchla utters five words and offers one "uh huh."

It's not rudeness, and it certainly isn't a lack of things to say, it's simply that the inventor of the Buchla box doesn't primarily communicate by talking.

Born in South Gate, California, Buchla's family was constantly on the move.

"I flew around all over the country. I was never in one place for more than a year," he says. "My father was a test pilot and he flew around to all the air force bases."

It was "a bit rough" for the family, Buchla says.

Attending Berkeley in the early 1960s, Buchla encountered a likeminded spirit in clarinetist and composer Morton Subotnick.

Subotnick had won musical acclaim, but he was striving to find sounds that would befuddle eardrums and transgress musical boundaries. He sensed electronics were the right path but he didn't know a transistor from an egg.

Buchla did.

As two musical revolutionaries with a $500 grant, Buchla built his first instrument.

"It was a turning point in that I finally had support for building instruments I was into building," he says.

The Buchla Box vaguely resembled the computers NASA used to launch the first monkey into space.

A Gordian knot of wires carry voltage from one outlet to another, covering the massive façade.

Thirty years later, Buchla created Lightning.

The hand-held MIDI cylinder - similar to the control used for Nintendo's Wii - senses gestures and responds with sounds. In a mid-1990s performance, Buchla's Lightning sounds like mice behind an attic wall, melancholy birds, an engine's unpleasant grumbling, a sensuous hum that defies description, and then everything at once.

Best known for penetrating documentaries dealing with racism and apartheid, Connie Field may seem like an unlikely choice to make a documentary about the notoriously loquacious Buchla.

"He can sometimes be shy, and then he can tell absolutely wonderful stories," Field says.

Field and her frequent editor Greg Sharpen took a break from shopping for an executive producer to discuss Buchla's often overlooked work.

"There's not very much written about Don or talked about Don anyways, but even that doesn't begin to cover all the other stuff which has never been talked about," Sharpen says, discussing Buchla's jobs as a firefighter and a NASA employee.

For Sharpen, Buchla's sense of whimsy sets him apart from other electronic composers.

Buchla's "Cicada Music," was a score for "around 2,500 six-legged performers," Sharpen recalls.

"We come at this from two different angles," Field explains. "Greg is very much into the whole musical genre of all of this, and I know Don."

Rather than simply pointing a camera at Buchla, Field says she's been filming him in social situations.

"Part of our technique is we were doing a lot of shooting of Don in conversation with other people that he knows really well," she says.

Buchla's career is often viewed in parallel with Robert Moog, the famed inventor of the synthesizer.

"As a person and as a performer he's somebody who I think has just never gotten his due," Sharpen says.

Buchla may be unable to look anywhere but ahead.

"That's just the way I'm wired," he says.

"My instruments are created mainly for my own use, so I know what I want. Turns out that there are quite a few people out there that more or less want the same thing. But I designed them for myself," he says. "I get satisfaction out of designing, and even more satisfaction out of playing the instruments."

Asked if his musical ideas come to him, Buchla responds: "No, they don't come to me, I have to go get 'em."

Now 76, Buchla remains committed to the future.

"I always felt that things were changing, or about to. I still do think that way."