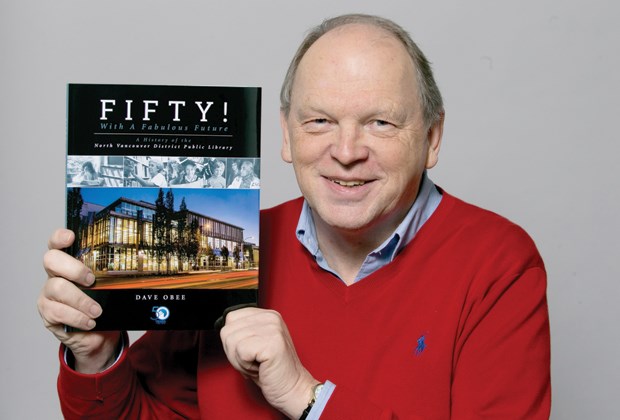

Author Dave Obee shows off a copy of his new book Fifty! With a Fabulous Future, a history of the North Vancouver District Public Library. A book launch is set for Saturday, Dec. 6, 7:30 p.m., at the Lynn Valley branch, 1277 Lynn Valley Rd., North Vancouver. Obee and cartoonist Adrian Raeside will both be in attendance. Tickets are $50, available at booklaunchsoiree.eventbrite.ca or any NVDPL branch, and include a copy of the book ($30 value), a drink and appetizers.

The following is an excerpt from the book:

“Librarian for new Municipal Public Library, North Vancouver District. A challenging opportunity for an experienced candidate having organizational ability, an outgoing personality and aptitudes in public relations.

“Qualifications: Degree from a recognized University and a degree or diploma in Library Science. At least three years responsible administrative experience.

“Salary from $7,000-$8,000/year commensurate with experience. The Librarian will be responsible to a Library Board to be appointed in January 1964, which will assume and extend the services now rendered by volunteer groups. Present population 45,000, present circulation 175,000.

“Applications addressed to C. McC. Henderson, Municipal Manager, P.O. Box 218, North Vancouver, B.C. will be received until January 31st, 1964.”

Enid Dearing saw that advertisement and submitted her application. It was a rare chance to become the first chief librarian in a growing, vibrant community – North Vancouver District. She won the job, and for the next twenty-seven years she worked hard to build the library and ensure it was connected with the public. Her vision – making service as accessible, convenient and friendly as possible – helped create the library of today.

She expressed her beliefs clearly at a library conference in May 1971 in Victoria. Libraries, she said, should “clear away the cobwebs of parochialism.” They should not see themselves as keepers of purchased material, but rather as “a supermarket dispensing world-generating ideas.”

Enid Mae Dearing was born on March 31, 1931 in Vancouver. Her parents, Ernest Mills Dearing and Lorna Matilda Bernard, had been married there in 1918, and had two daughters, Elinor and Ina, before Enid was born. At the time of her birth, her father was a life insurance agent, and later worked in the lumber industry. The family lived on Gray Avenue in Burnaby until 1942, then at 4034 West 16th Avenue in Vancouver, just east of the University of British Columbia.

Enid attended the University of British Columbia and attained a Bachelor of Arts degree in 1952. In a 1991 interview with the North Shore News, she said that when she graduated, women were supposed to be teachers, like her sisters Elinor and Ina, or nurses or social workers. “I didn’t want to do any of that, so I went to work in the University of B.C. library.”

She spent five years as a library assistant, working in the serials division among other areas. Then she decided to attend library school. As UBC did not have one yet, she attended McGill University in Montreal. She graduated in 1958, and that July was hired as the Nanaimo branch manager for the Vancouver Island Regional Library.

The Nanaimo job was not easy, since for thirty-four years, the branch had been in an old house on Wallace Street with a coal furnace and no electric outlets. “The Nanaimo library was famous, or more correctly infamous, for being the worst library building in the province,” Dearing wrote later.

In September 1960, Dearing was promoted to headquarters as assistant regional librarian, the second-in-command of the system. The posting for the job specified that it would include “considerable administrative responsibility.” The Island library had six deposit stations and two bookmobiles, but Dearing’s main assignment was to find better locations for the system’s sixteen branches.

In Nanaimo, Dearing worked with two of the province’s library greats, who had taken jobs in the regional system after retiring from bigger jobs. C.K. Morison was the former superintendent of the Public Library Commission, and Margaret Clay had succeeded Stewart as head librarian in Victoria. Morison and Clay were more than just Dearing’s co-workers; they were critical influences in her career, providing inspiration, knowledge, and later, job references to help her advance to the head librarian’s position in North Vancouver.

Just thirty-two years old when she was hired in North Vancouver, but with solid experience in library administration, Dearing attacked the job with energy and enthusiasm. She was a hands-on manager, and in the beginning, did much of the work herself.

During her first summer, she read stories to children on the lawn of the Capilano branch. She also moved books between the branches, using her own car for the first two years in order to keep costs down. As well, she raised the profile of the library, speaking to local organizations and conducting tours of the facilities. Kindergarten groups were welcome, because Dearing believed in teaching the value of the library at an early age.

She worked quickly to ensure the independent volunteer libraries worked together, and hired staff members. She said in a 1971 interview that she spent most of her time dealing with the staff in headquarters and the branch libraries. “I try to keep the paperwork to a minimum,” she said. “My special interest is in the book selection for the three libraries, which I handle personally whenever possible.”

In May 1971, Dearing took part in the B.C. Centennial Citizens’ Conference on Libraries in Victoria, which encouraged more development and more sharing. She pushed her fellow librarians, reminding them that they needed to look beyond their walls, and reach out to the people who did not use their services.

“Priorities must be established to concentrate efforts to reach the great unserved,” she said. “Libraries will be required to inject resources and staff skills into many types of programs designed to reduce functional illiteracy, to contact those individuals in the lower socio-economic brackets, and to reach sections of the population who, through indifference or lack of education, do not know of library services.”

Dearing devoted herself to improving libraries and library service well beyond the North Shore. In 1973, she worked with the Cariboo Thompson Nicola Library System to set up a demonstration bookmobile. Two years later, she gave a week of lectures at the library school at the University of Alberta in Edmonton. In 1981, she gave a workshop on library buildings at a conference in Prince George.

She was also involved in provincial and national organizations. She joined the British Columbia Library Association in 1958, then volunteered for committees and worked on annual conferences. In May 1966, she was elected to a one-year term as association president. She was key to the creation of the Greater Vancouver Library Federation in 1975, a development that led member libraries sharing their resources at an unprecedented level.

Late in her career, Dearing researched and planned an automated circulation system for the library. It went into operation on May 29, 1991, a month before she retired.

Throughout her career, Dearing witnessed dramatic changes in technology – from pen and paper to computers. She gave an example from her time at McGill University in Montreal. “When I was in library school, as a class we went down to the CPR station and looked through the window and watched men in white shirts working on computers,” she said years later. “Computers had just started to come on the scene and that was our computer training, peering through the window.”

She said as she retired in June 1991 that her only regret was that in the later years of her career, most of her time had been taken up with administrative responsibilities. That meant that she did not have day-to-day contact with library users. “In the early days I worked with the public,” she said. “I miss that.”

June Soper, who chaired the library board for two years in the 1970s, described Dearing as the most dedicated person she has ever known. “The library was her passion and her enthusiasm was contagious,” Soper recalled. “Everyone that she came in contact with would become just as passionate about the library and what was going to be its future.

Today, the District’s first librarian is remembered with the Enid Dearing Room in the Parkgate branch, which opened later in the year she died. There is also the annual Enid Dearing/Alan Woodland Book Prize, established by the Greater Vancouver Library Federation in 1991, awarded to a student at the School of Library, Archival and Information Studies at the University of British Columbia for outstanding work in courses related to public librarianship.

Dearing had a lasting impact on the District library. As the first head librarian, she set the stage for the development of the system, and for more than a quarter of a century turned her vision into a reality. By the time she left, the library had three strong branches – two in dedicated buildings, and a plan in place for the third.