She was captivated by the way he ran.

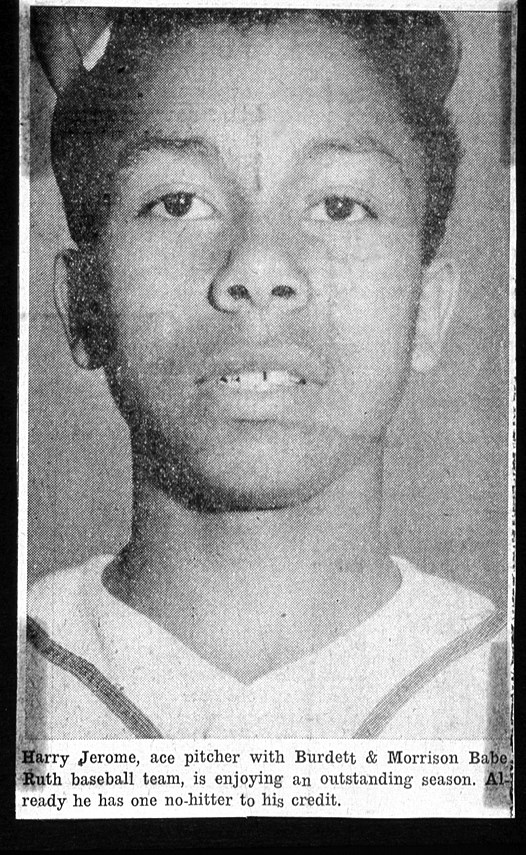

Harry Jerome had a “completely effortless stride,” author Norma Charles recalls.

He was a power runner who moved with the fluidity of a cosmonaut drifting through zero gravity – but it didn’t come easily.

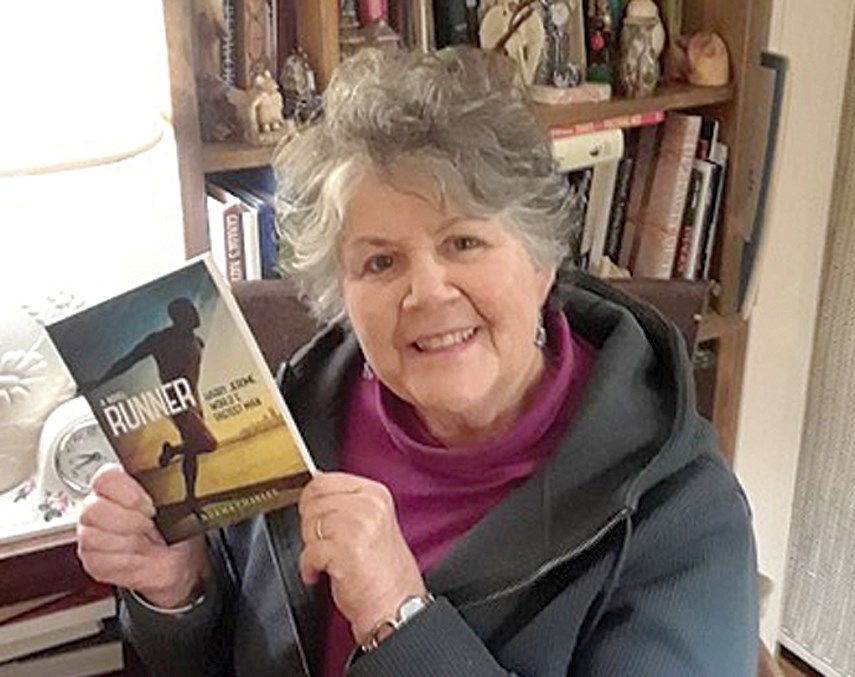

Charles’ young adult novel Runner: Harry Jerome, World’s Fastest Man dramatizes the life of North Vancouver’s greatest sprinter and chronicles the sweat, grit and unrelenting effort that went into perfecting that effortless stride.

Charles begins the action in Jerome’s childhood home in St. Boniface, Man., on the night the Red River jumped its banks and flooded the predominantly French community out of their homes.

At nine years old, Jerome is yanked from his Superman comic book and a squabble with his sisters over who should rightfully be expected to wash the dishes.

Along with his fellow cubs, Jerome drags sandbags across the road to waiting soldiers doing their best to contain the river.

Charles describes the moment the river escaped and: “rushed toward Harry like a runaway bull.”

The flood changes the course of Jerome’s life. Appraising the aftermath and unaware of the hostility awaiting them, Jerome’s father opts to move the young family to North Vancouver.

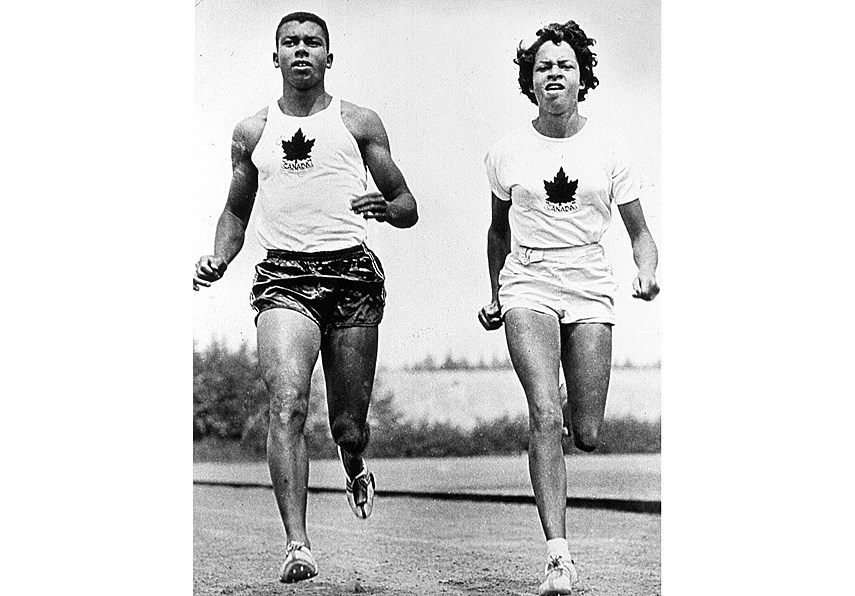

It’s on the North Shore that Jerome begins a sprinting career that sees him set a national record as an 18-year-old high school kid and win gold at the Pan Am and Commonwealth Games.

But watching from the stands, Charles writes that Jerome seemed: “quiet, shy, reserved. Not ‘one of the guys ... .’”

That perceived standoffishness may stem from the bigotry of Jerome’s North Vancouver neighbours. Charles describes a joyless woman handing the child an envelope with an instruction to pass it on to his parents. It was a petition, signed by many of the neighbours, asking the Jerome family to move away from the “whites only” neighbourhood.

Charles imagines what Jerome might have thought as he listened to his father blast the ignorance that co-signed the petition.

Jerome agrees with his father, mainly.

“But deep, deep down inside himself, so deep down that no one would ever suspect it was there, was a tiny voice that whispered: Maybe they’re right . . . Maybe they really weren’t good enough to live in such a nice house ... .”

The reader tags along with Jerome and his sisters on what was to be their first day at their new elementary school.

The children greet the new kids with taunts and racial epithets. One throws a rock. Jerome throws one back. A gang forms, chasing the siblings and: “pelting them with rocks, calling them names, yelling at them to go home.”

Much of the narrative stems from conversations with Jerome’s sister, Valerie Jerome.

“I spent the day with her and peppered her with all kinds of questions,” Charles says. “She told me lots and lots of things that I hadn’t read about.”

Charles toyed with the idea of writing a non-fiction account of Harry Jerome’s life, but the words didn’t quite “fly off the page,” she says.

But the notion of writing a young adult novel about the legendary sprinter appealed to her. “In a novel you can really get into a person’s self, into his head, into his heart,” she says.

Charles also recognized a dearth of stories for black Canadian children.

“There were no books for children about this great Canadian hero. None,” Charles writes in the book’s introduction. “In fact, there are very few books for children about any Afro-Canadians.”

Charles saw Jerome’s story as a powerful example for her own grandchildren.

“I was really, really astounded at his determination,” she says. “His sheer stick-to-itiveness.”

Jerome tore his quadriceps while competing for Canada at the 1962 British Empire and Commonwealth Games. Friend and distance runner Bruce Kidd later said the hole in Jerome’s leg was as big as his fist.

But to critics in the media, his last-place finish was evidence that he was a mentally fragile quitter.

“Anybody else I think would’ve just said, ‘I’ve had my day, thank you very much.’ But not Harry,” Charles reflects.

After undergoing the rigours of rehab, Jerome competed and earned an Olympic bronze medal at the 1964 Tokyo Olympics.

“I think it had a lot to do with his earlier experiences of feeling that people didn’t respect him and his family very much and so he was going to show the world,” Charles says. “The real story was how this kid, with very little encouragement from home or elsewhere, just put his head down and did what he had to do.”

Jerome died in 1982.