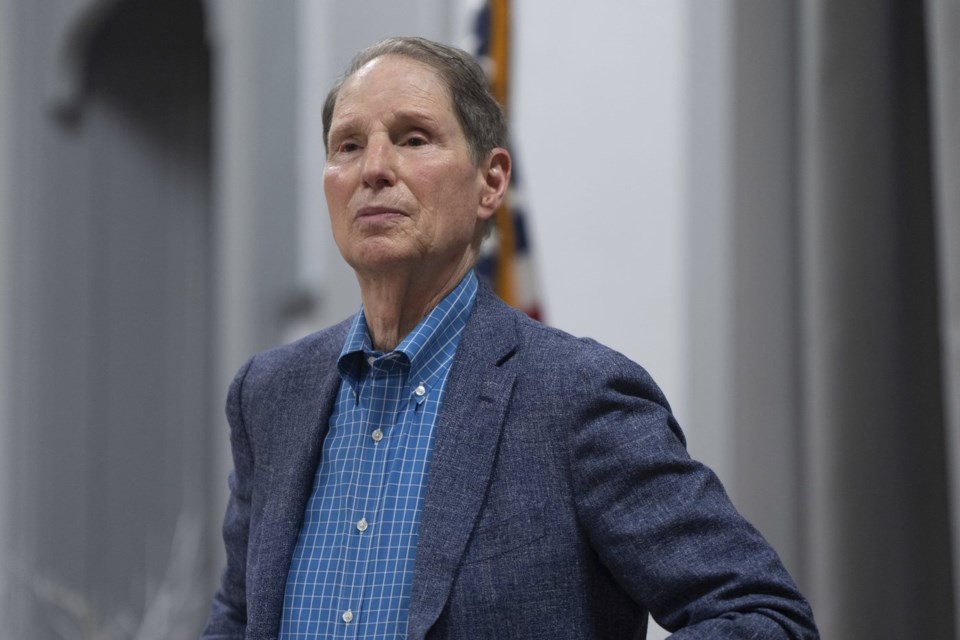

WASHINGTON (AP) — The Trump administration is planning to remove nearly 700 Guatemalan children who had come to the U.S. without their parents, according to a letter sent Friday by Sen. Ron Wyden of Oregon.

The removals would violate the Office of Refugee Resettlement's “child welfare mandate and this country’s long-established obligation to these children,” Wyden told Angie Salazar, acting director of the office within the Department of Health and Human Services that is responsible for migrant children who arrive in the U.S. alone.

“Unaccompanied children are some of the most vulnerable children entrusted to the government’s care,” the Democratic senator wrote, asking for the deportation plans to be terminated. “In many cases, these children and their families have had to make the unthinkable choice to face danger and separation in search of safety.”

Quoting unidentified whistleblowers, Wyden’s letter said children who do not have a parent or legal guardian as a sponsor or who don’t have an asylum case already underway, “will be forcibly removed from the country.”

It is another step in the Trump administration's sweeping immigration enforcement efforts, which include plans to surge officers to Chicago for an immigration crackdown, ramping up deportations and ending protections for people who have had permission to live and work in the United States.

The White House and the Department of Health and Human Services did not immediately respond to requests for comment on the latest move, which was first reported by CNN. The Guatemalan government declined to comment.

“This move threatens to separate children from their families, lawyers, and support systems, to thrust them back into the very conditions they are seeking refuge from, and to disappear vulnerable children beyond the reach of American law and oversight,” Wyden's letter says.

Due to their young age and the trauma unaccompanied immigrant children have often experienced getting to the U.S., their treatment is one of the most sensitive issues in immigration. Advocacy groups already have sued to ask courts to halt new Trump administration vetting procedures for unaccompanied children, saying the changes are keeping families separated longer and are inhumane.

In July, the head of Guatemala’s immigration service said the government was looking to repatriate 341 unaccompanied minors who were being held in U.S. facilities.

“The idea is to bring them back before they reach 18 years old so that they are not taken to an adult detention center,” Guatemala Immigration Institute Director Danilo Rivera said at the time. He said it would be done at Guatemala’s expense and would be a form of voluntary return.

The plan was announced by President Bernardo Arévalo, who said then that the government had a moral and legal obligation to advocate for the children. His comments came days after U.S. Homeland Security Secretary Kristi Noem visited Guatemala.

Migrant children traveling without their parents or guardians are handed over to the Office of Refugee Resettlement when they are encountered by officials along the U.S.-Mexico border. Once in the U.S., they often live in government-supervised shelters or with foster care families until they can be released to a sponsor — usually a family member — living in the country.

They can request asylum, juvenile immigration status or visas for victims of sexual exploitation.

The idea of repatriating such a large number of children to their home country raised concerns with activists who work with children navigating the immigration process.

“We are outraged by the Trump administration’s renewed assault on the rights of immigrant children,” said Lindsay Toczylowski, president and CEO of Immigrant Defenders Law Center. “We are not fooled by their attempt to mask these efforts as mere ‘repatriations.’ This is yet another calculated attempt to sever what little due process remains in the immigration system.”

___

Gonzalez reported from McAllen, Texas. AP writers Sonia Pérez D. in Guatemala City and Tim Sullivan in Minneapolis contributed to this report.

Rebecca Santana, Amanda Seitz And Valerie Gonzalez, The Associated Press