A Vancouver city council meeting Tuesday on a proposed overdose prevention site near upscale condos and apartments in the Yaletown neighbourhood highlighted deep divides over the response to the deadly overdose crisis.

More than 100 people signed up to speak to council about the proposed indoor overdose prevention site.

Some, like Overdose Prevention Society founder Sarah Blyth, said overdose prevention sites, where substance users are observed and supported, would save lives and reduce problems like discarded needles.

Others, like Jon Malach of the Downtown Community Safety Watch, said the site would harm the neighbourhood and likened harm reduction services to making “taxpayers fund the terror they experience every day.”

City staff, Vancouver Coastal Health and other advocates say the transition to an indoor site is essential to save lives in the area and will actually reduce the kinds of issues opponents raised at the meeting.

So far in 2020, 259 people in Vancouver have died of an overdose. Across the province, 1,068 people have died this year.

About one in seven of Vancouver’s more than 2,000 911 overdose calls so far this year happened in the area served by the proposed site in a building two blocks from the city’s busy Granville strip.

“An overdose prevention site in this facility would be life-changing,” said Guy Felicella, a peer advisor with Vancouver Coastal Health and former substance user. A similar facility “gave me that relationship with people and the confidence and the ability for me to improve the quality of my life,” he told council.

Many housed residents raised concerns ranging from issues with the 1101 Seymour St. site’s proximity to Emery Barnes Park to a perceived lack of consultation.

These speakers included organizers Michael Geldert and Dallas Brodie of Safer Vancouver, which has links to homeowner groups in the expensive Shaughnessy neighbourhood and has been raising concerns about safety downtown.

Safer Vancouver is critical of harm-reduction services and is calling for an audit of how money is spent on services in the Downtown Eastside.

As a health service, there are no limits on how close an overdose prevention site can be to a playground or school as there are for liquor and cannabis stores.

And because it is an emergency measure to curb overdose deaths under the Public Health Act, Vancouver Coastal and the city do not have a formal duty to consult the community before proposing the location.

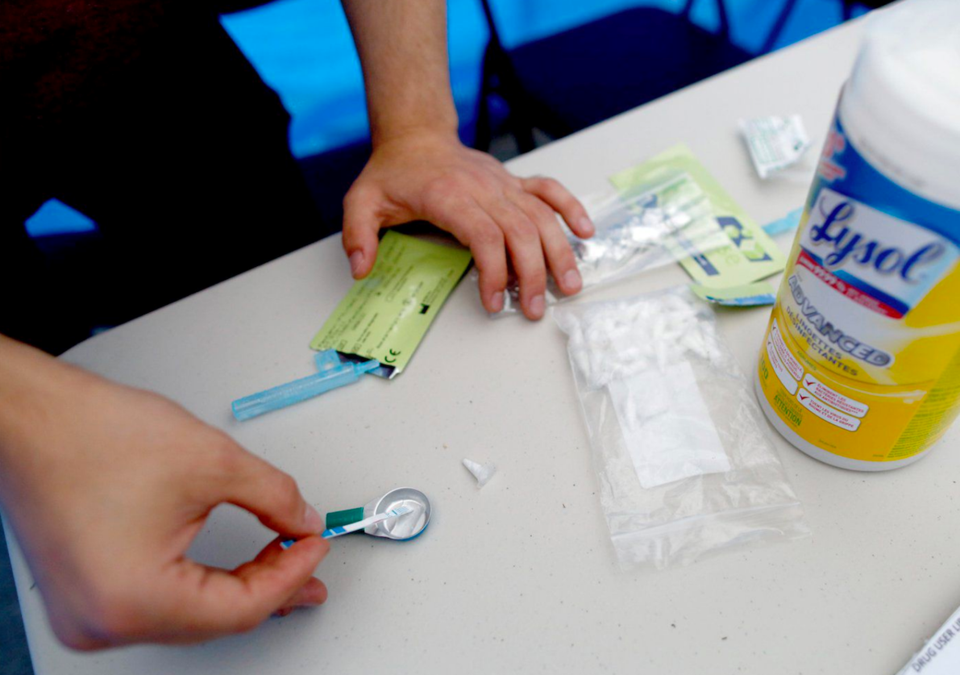

There is currently a mobile site operating eight hours per day in a van outside the proposed permanent site. It would move to another area once an indoor site is established, which could be as early as November.

City staff said they had been searching for a place to move the current overdose prevention site operating out of a trailer outside St. Paul’s Hospital on Thurlow Street.

Capacity would remain the same, they said. Services would merely move indoors into a larger and more appropriate space.

Chris Van Veen, Vancouver Coastal Health’s director of strategic initiatives and public health planning, said the authority and city have engaged housed residents and business owners through a community engagement committee, and will continue a dialogue if the proposal is passed and operational planning begins.

“The backlash to this one has been unique,” Van Veen told council. “But delaying the site for months to undertake a giant community consult process would lead to more deaths.”

“The important thing is to prove to communities that [overdose prevention sites] can operate with little impacts or positive impacts.”

Many residents raised concerns about discarded needles and outdoor drug use in the neighbourhood, which they said increased rapidly in the last six months since the city cleared the Oppenheimer Park tent city and rehoused many people in the newly purchased Howard Johnson hotel near the proposed site.

Some expressed fear for their children or elderly neighbours, who they say are anxious about walking around the neighbourhood alone.

Blyth said overdose prevention sites work at being good neighbours and that having indoor services would mean people could use drugs safely and lessen discarded needles and supplies.

“[The sites] alleviate some of the issues the community members were talking about,” said Blyth. “I’m at wits’ end with all the people dying.”

While a number of residents who opposed the sited stressed that they want these services to exist where people need them but perhaps not near a park, several others were hostile towards people who use drugs and those who offer life-saving services.

Nearby strata president Nadia Iadisernia, also associated with Safer Vancouver, said drug users “have no respect for society or themselves” and she didn’t want “this in her neighbourhood.”

When asked by a councillor whether she believed the evidence that more services would reduce the issues she’s concerned about, Iadisernia said that was “rewarding everyone for their bad behaviour.”

Several speakers opposed the site compared the neighbourhood to a “war zone,” language that speakers in favour of the motion said further stigmatizes people who use drugs, putting their lives at greater risk.

Acting chair Christine Boyle and Mayor Kennedy Stewart intervened several times to keep speakers respectful.

Speakers in support of the new site focused on the importance of saving lives as COVID-19 pandemic measures contribute to an increasingly toxic drug supply and rising overdoses.

Trey Helten, a manager at Overdose Prevention Society who has experienced homelessness and entrenched drug use, says he lost three friends to overdoses one night years ago, just blocks from the site.

“They didn’t have a choice to use safely,” said Helten. “It seems many of these Yaletown folks think we are just bums... it’s insulting.”

Garth Mullins, a board member of the Vancouver Area Network of Drug Users and the BC/Yukon Association of Drug War Survivors, spoke of his own experience using drugs in the area as a teen, before it began to gentrify.

“People who use drugs were here before developers came,” said Mullins. He used to use inside his apartment or a washroom and quickly pack up his things and get outside in the hopes someone would see him if he overdosed and call for help.

“The people opposing this, they want us to go back... and we can’t go back,” said Mullins. By opposing this proposal, he said, “they’re basically saying their whole neighbourhood will continue to be an unsafe injection site.”

A number of councillors asked city staff and speakers if the limitations of the site were reasons not to move forward with the proposal. For example, the small space does not have a space for inhalation of substances like crystal meth, which contribute to an increasing number of fatal overdoses in B.C.

But advocates said that concerns about getting something perfect the first time should not eclipse the need to save lives.

“It’s not all or nothing. You build the safe injection site, and you fight like hell for the safe supply to go with it,” said Mullins. “A vote against today’s motion would just be pushing back against drug users.”

Council had heard 56 of 115 slated speakers by Tuesday afternoon as the meeting continued into the evening. Debate and a vote is scheduled to take place Oct. 20.

Moira Wyton is a Local Journalism Initiative reporter with The Tyee, where this story first appeared.