It didn’t used to be this way.

Unless there was a stall or accident, cars used to zip down the Cut each afternoon, hit the Ironworkers Memorial Second Narrows Crossing and disappear to all points south of the Burrard Inlet.

Then, sometime in late 2012, the Cut started becoming routinely backed up to Westview Avenue, and other feeder routes to the highway along Keith Road, Third Street and Low Level Road became equally clogged.

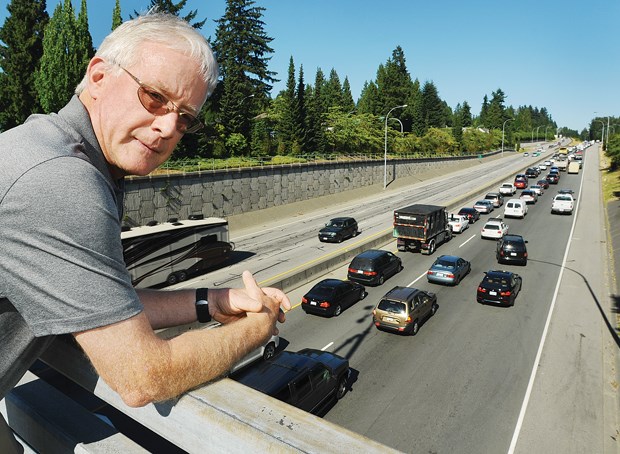

“You talk to anybody on the streets of the North Shore and ask them, ‘What’s the major issue here?’ They’ll say it’s the traffic that emanates from the bridgehead,” says District of North Vancouver Mayor Richard Walton.

The Ministry of Transportation and Infrastructure hired a consultant more than a year ago to help figure out why the daily traffic flow between the top of the Cut in North Vancouver and Willingdon Avenue in Burnaby has gotten so bad in recent years — and what can be done about it.

It’s a question of numbers and a theoretical tipping point where a busy highway turns into a parking lot.

Traffic engineer Jason Jardine presented an update on the study to District of North Vancouver council members on June 22 and its conclusions so far aren’t what most people would expect.

The increasing traffic woes on the North Shore aren’t caused so much by more people living here as they are by more people working here, the study suggests. And they’re coming to work in one industry in greater numbers than ever before — residential construction.

Though that may conjure up images of work crews on highrises, the building boom is mostly being felt in single-family neighbourhoods.

“Quite often, the situation is a lot more complex,” Walton said. “We know a lot more information than we did a year ago and we have to understand that information before we can make meaningful solutions because they can take 10 or 15 years of shifting investment and policy to address.”

According to the last 10 years of data, the North Shore’s population has been growing by about half a per cent per year while the total number of daily trips over the Ironworkers Memorial Second Narrows Crossing grew at a slightly slower rate.

But, along with changing demographics and ballooning land prices, there’s been a shift in commuting patterns.

The percentage of North Shore residents who also work on the North Shore has risen from 46 per cent to 50 per cent, but the number of people commuting from south of the Burrard Inlet has gone up by 14 per cent from 17,260 to 19,660 according to the census data.

Jardine compared that number with the volume of building and demolition permits granted by the North Shore’s three municipalities and found similar growth, suggesting much of the new traffic is building contractors coming to work on North Vancouver and West Vancouver homes.

“I would say there’s a strong pattern that tends to support that observation,” Jardine said.

The census numbers likely don’t capture many of the subcontractors who are only here working on a job site for a couple weeks at a time, Walton said.

The situation is likely to get worse before it gets better as many older single-family homes and apartments are considered tear-downs now. Walton estimated two-thirds to three-quarters of those permits and workers are related to rebuilding older homes, rather than highrise construction.

“The North Shore is now entering into a period where for the next decade, we’re very, very heavily building out old, wooden, family housing stock, which means we’re going to have significant numbers of trades folks working in neighbourhoods where they had no presence 20 years ago,” Walton said.

Those extra workers, combined with employment growth happening on the North Shore’s expanding industrial waterfront, have pushed the stressed highway beyond its tipping point — somewhere between 4,000 and 4,500 vehicles per hour.

In the two years since the new Port Mann Bridge opened in 2012, there have been disproportionate jumps of .6 per cent and 1.7 per cent in daily traffic over the Second Narrows bridge.

When a road hits its maximum capacity, the queues of idling vehicles and the amount of time rush hour lasts both just get longer. “Rush hour” with near-to or over-capacity traffic on roads leading to the Second Narrows bridgehead now extends from 2 until 6 p.m., according to the study, and that’s assuming there are no accidents or stalls.

“I think we’ve been close to that tipping point for many years now,” Jardine said. “You can get a certain amount of traffic through a bottleneck and when things fail, they fail very badly. . . ”

Making matters worse is the 50-year-old highway interchange system that doesn’t reflect modern best practices, Jardine said. The worst choke point when leaving the North Shore in both the morning and evening: the weave between the Fern Street on-ramp and Main Street off-ramp as well as the Dollarton Highway entrance to the bridge. The commute spoilers for driving on to the North Shore: The Hastings on-ramp, Dollarton/Main street exits, the weave between Dollarton and Seymour and the merge from Fern Street before the Mountain Highway off-ramp.

The study also looked into heavy trucks and found they only account for about two per cent of the crossings. Truckers prefer to avoid rush hours, with peak truck traffic happening during the middle of the day. Though traffic coming from B.C. Ferries vessels at Horseshoe Bay has been going down, one full ferry can put up to 370 more vehicles on the road.

The study, which the City of North Vancouver and the District of West Vancouver are also keeping a close eye on, should help focus the municipalities on how to resolve the problem.

“‘Traffic’s a nightmare. Growth is out of control.’ That’s the standard mantra that we hear. Well, growth is not out of control but traffic is obviously getting worse so let’s get at the traffic and understand the issues and make sure any response we have on the North Shore from any of our local governments is based on a very cogent analysis of the facts, rather than the perceptions,” Walton said.

Taking a scolding tone against commuters won’t help, Coun. Roger Bassam warned. “Those are jobs. Those are people who work here. . .” he said.

He suggested North Shore residents also look at their own habits before pointing fingers.

“A lot of it is local traffic. We could maybe make better choices around not driving six trips in a day.”

The study’s results come as massive dollars are about to be spent on bridgehead infrastructure.

The province, district and federal government have already announced plans to build a new $50-million interchange at Mountain Highway, scheduled to open in 2018.

The district is currently widening the Keith Road bridge to five lanes and connecting it to the Fern Street overpass at a cost of $12.7-million. That project is intended to create a new east-west route over the highway so commuters headed home to Seymour or Deep Cove aren’t sharing limited lanes of traffic with bridge commuters.

All three governments are also looking to share in the $100-million cost to update the remaining interchanges leading to the bridgehead.

The North Shore has long been overlooked by the province when it comes to transportation infrastructure spending, Walton said.

“The one place in the entire TransCanada Highway between Squamish and now Chilliwack that has not had virtually a nickel put into it is our community — Lynn Valley to the Ironworkers Bridge,” he said.

But, even if we untie all the traffic knots before the bridge, the Ironworkers itself will be unable to handle much more capacity, Jardine said. In theory, the bridge could handle 1,800 vehicles per lane, per hour heading eastbound. With the bridge already accommodating more than 5,000 vehicles per hour in its three eastbound lanes during peak periods, it’s only a matter of time before the bridge starts to look like the Cut.

The province and the consultant are now taking a detailed look at what mitigation measures could be taken, including re-evaluating the ones already being proposed “to make sure we’re actually going to get the kind of performance improvements that we want,” said David Stuart, the District of North Vancouver’s chief administrative officer.

When it came to looking for ways to mitigate the current mess, Coun. Mathew Bond suggested the district focus on not just increasing the supply of road space, but also managing demand.

“Looking at these charts, if we took 400 vehicles off the road during the peak hour, that would solve our problem. We’d go back to where we were three or five years ago and we wouldn’t have these issues,” he said. “How much does it cost to take 400 vehicles off the road compared to expanding all the infrastructure to supply another 400 vehicles?”

That question became especially relevant Thursday when Lower Mainland residents learned the results of the failed TransLink funding plebiscite. Had it passed, the North Shore would have got three new B-line bus routes, as well as 50 per cent more SeaBus service, and more regular buses.

The loss is being deeply lamented by Walton. “There’s no doubt. If you’ve got a bus with 50 people on it, that replaces 50 cars. That’s a huge shift,” he said.

The Lower Mainland’s mayors estimated the .5 per cent sales tax would have cost the average Lower Mainland household between $150 and $250 per year. By comparison, if North Shore residents were asked to pick up one third of the cost of building a new wider Ironworkers Bridge, Walton estimated that would cost local taxpayers about $400 million.

“That’s an awful, awful lot of money for the North Shore tax base,” he said. “Big concrete things and heavily engineered things are very expensive and it may be the champagne solution but there’s not even a guarantee that would suffice for more than five or 10 years before it reached capacity.”

One other way to manage demand is to introduce road pricing. Stockholm’s traffic congestion was remarkably similar to our own right up to the point its residents approved road pricing in a referendum.

“The next day, literally, the cars were back to . . . 100 kilometres per hour at a time when they were congested the day before. The impact of taking that much traffic out is profound,” Walton said.

Though our own plebiscite loss was deeply disappointing to Walton, he said the issue of transit improvement is far from dead.

“I’m not backing down for a second. I’m going to keep talking and pushing transit as a critical issue. This is a set-back but it’s not a permanent set-back,” he said.

The final report on Highway 1 traffic gridlock is due this fall.

Follow Brent on Twitter: @BrentRicter