The Royal Air Force’s 214 Squadron only flew bombing missions in the dark. But the cover of night didn’t make them totally invisible as they zeroed in on German cities and industrial targets during the Second World War.

Anti-aircraft guns lit up the blackness with explosive orange bursts and the Luftwaffe’s “night fighters,” equipped with sophisticated radar and weaponry, hunted for Allied aircraft in the dark.

Despite the danger lurking during the nighttime sorties, Canadian pilot Jack Henderson never second guessed his decision to sign up for the Royal Canadian Air Force.

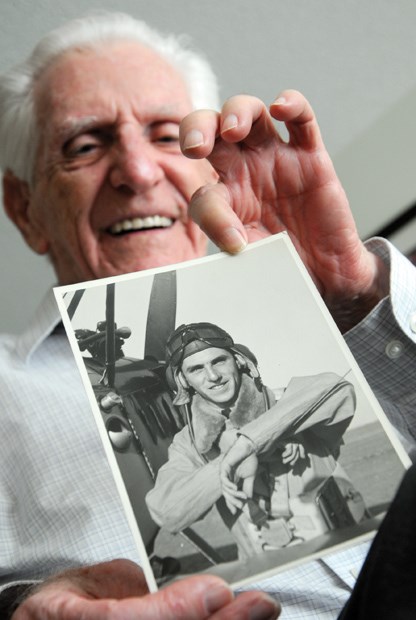

“I refused to join the army and the navy,” explained the 96-year-old veteran, sitting inside his North Vancouver apartment, flipping through his wartime photo album. “I knew too much about the ocean and had too many uncles who were in the First World War in the army! That made up my mind.”

So when war broke out in Europe, Henderson marched to the local recruiting office and signed up for the air force. He was 20.

“But I had a problem. I had no flying experience,” he said. “I thought, bang, I’d be in airplanes. ... They wouldn’t even talk to me.”

Instead, recruiters coveted the thousands of Canadian pilots who’d already earned airtime as bush pilots or commercial captains. Henderson waited two years before he landed at a Canadian training base to earn his wings. After learning about flying, bombing and gunnery, he was sent to Liverpool, England, in 1944.

It took another six months of training aboard an assortment of planes and bombers before he was assigned to an RAF crew.

“The 214 Squadron was where I became very active,” he recalled.

Henderson piloted a Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress, an American-built high-altitude airplane.

“We were the only squadron flying an American four-engine bomber,” he explained. “I loved it. They were an amazing aircraft. Huge, 1,400-horsepower each engine, power, power, power… as a matter of fact, we came home once on two engines.”

Henderson has a few photos of his crew and the plane in his album – the only wartime mementos he has left after a flood destroyed a trove of keepsakes he’d stored in cardboard boxes.

“We weren’t allowed to carry a camera,” he said, with a mischievous grin.

But inside the front pocket of his uniform he kept a small, folding camera that looked like a cigarette case.

“Every once in a while I could sneak a picture, as you can tell ... but everything else was forbidden, particularly of the aircraft and things like that.”

During the bombing raids, Henderson’s plane flew 2,000 feet above the “stream” of bombers, which ranged in number according to the mission from 250 to 1,000 planes, and used electronic countermeasures to jam German radio signals, among other things.

“Special work to protect the other pilots. We carried no bombs, only special equipment.”

Despite being at a higher altitude, they still encountered mortars and night stalkers.

“We flew at night only,” he explained. “What you do have is some exhaust that once in a while gives you trouble. You get near the target, you have all the flames from the town burning and you become background — they can see you coming in. We were attacked a few times but seldom.”

German night fighters posed the greatest danger.

“They travelled at night looking for us. With radar, they can catch you at a distance. (The Germans built) special planes for night flying with guns on them to shoot us down.”

The night fighters were fast and manoeuvrable so RAF pilots had to rely on cunning flying skills and evasive measures to give the enemy the slip.

“Somebody would spot something. We avoided a few night fighters that way. Corkscrew starboard or port – we’d drop 500 to 1,000 feet,” he said, using his hands to demonstrate.

Those abrupt altitude changes managed to thwart enemy attacks but they came at a price.

“Why do you think I’m wearing these?” he said pointing to his hearing aids. “That’s one of the impacts you have … you’re diving. We’ve got to change altitude fast.”

Remarkably, after participating in numerous missions in hostile territory, Henderson and his crew remained unscathed.

“No one in my crew was touched; I was the most popular pilot in the whole squadron,” he said, laughing. “We never got hit once. We were chased by night fighters, we were flying through flak over bomb sites and our airplane was not touched. They figured that Berlin that last year of the war had at least 1,000 anti-aircraft guns that you were flying through.”

He recalls with a tight smile that one of his crewmen did suffer an injury but it didn’t come at the hands of the enemy. “Getting out of the airplane … he fell down the steps and broke his arm. That was the most serious wound we had.”

After the war ended, Henderson kept in close contact with his crew, who hailed from England, Australia, New Zealand and Canada, and made overseas trips to reconnect with them.

The shared experience of the war connected them forever.

“It’s huge. Especially with … there was no blood on our ship because of the work of every guy that was on there.”

One member of his original crew is still living in England, said Henderson, who still lives on his own and drives and exercises regularly.

After the war it wasn’t easy for Henderson to get a job as a commercial pilot because there was a flood of ex-bomber pilots in the market and most of them had three times the number of flying hours that he’d accumulated.

Despite grounding his flight career, the trajectory of Henderson’s life was just taking off after he returned from the war. He fell in love with a beautiful woman named Irene, got married, and moved to the Okanagan to raise a family and start a successful career in wholesale electronics.

Each year, when the calendar turns to Nov. 11, he remembers his crew and his experiences overseas.

“It’s a strange feeling. It was a terrible situation – the world war – of course, but the ability of mankind to work together to achieve things was incredible. What we could do and did do. What we put up with was huge even at its best,” he said. “It makes me proud of a lot of people.”