Like afternoon traffic on the Cut, the province is lurching forward with a redesign of the Mountain Highway interchange.

But even more substantial plans to replace the 1960 orange, steel Highway 1 bridge over Lynn Creek with a nine-lane alternative are now on the table.

The province debuted the original plan almost a year ago, as part of a $140-million overhaul of all three interchanges north of the Ironworkers Memorial Second Narrows Crossing bridgehead.

In broad strokes, the redesign includes a new four-lane Mountain Highway overpass, bicycle infrastructure, controlled intersections, a new on-ramp onto the Cut northbound and southbound off-ramp leading to Brooksbank Avenue.

But the one thing it lacked, according to several critics and armchair engineers, was a new onramp joining eastbound Highway 1. District and provincial staff looked into it and came to the conclusion that the orange bridge has got to go.

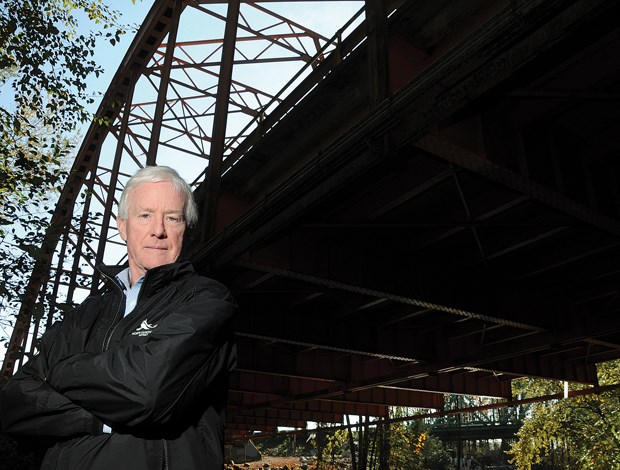

“That was not through lack of public will and engineering creativity. It simply isn’t physically possible because of land contour,” said District of North Vancouver Mayor Richard Walton. “It became apparent during the last number of months that, from an engineering point of view, you can’t do that eastbound access from Mountain Highway onto the highway without that bridge being widened.”

During his campaign, newly elected North Vancouver Liberal MP Jonathan Wilkinson promised federal money to replace the Lynn Creek bridge as the “Cure for the Cut.”

Under an update posted by the Ministry of Transportation and Infrastructure this week, the final designs should be ready by the new year and construction is due to run from summer 2016 to 2018.

Those plans, however, do not include the replacement bridge.

The estimated cost of replacing the bridge is $50 million. The province had it in its long-term plan to do after the Mountain Highway, Mount Seymour Parkway and Main Street interchanges were all revamped, but now the municipality is asking the province to fast-track the bridge replacement to get the Mountain Highway interchange project off on the right foot.

Should the province agree, the district is aiming for the replacement bridge to include another two-lane, east-west local road not connected to the highway in order to link Seymour to Mountain Highway.

“If you’re going to build a bridge of a certain capacity for the highway, why would you not piggyback on that?” Walton said.

But even if the interchange projects help untie the traffic knots and allow better east-west flow, a traffic study by the district and province found that the six-lane Ironworkers too is nearing its capacity and replacing the Ironworkers isn’t on anyone’s radar.

The appropriate response, Walton said, is stemming the number of people who choose to commute by car during rush hour.

“Certainly future investment in public transit is going to provide people an option that some people don’t have right now in deciding how to get to work,” he said. “If we can peel off even 10 or 15 per cent of the traffic, it can have huge impacts on the backups and volume at peak times.”

And Walton said the region needs to start charging for how and when people make use of the roads. “Building bridges is a multibillion dollar proposition and the entire Metro Vancouver area I think ultimately is going to have to take a look at incentivizing people to travel off-peak and travel on alternatives,” he said. “We all know the mantra in transportation engineering and design: You can’t build your way out of congestion. If you increase road capacity dramatically, you’ll simply encourage people to keep trying to go in their cars at peak time. With a growing city, that’s simply not possible. That’s a regional issue.”

The district will host a council workshop on the interchange project on Nov. 9. The public is invited; however, a separate public consultation process to refine the designs will follow soon after.