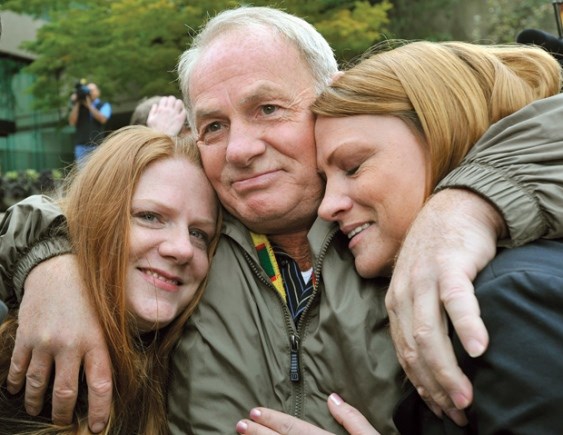

When her father was arrested, Tanya Olivares’s world “kind of crashed down” on her and her sister, the beginning of an ordeal that played out for them for nearly three decades.

Olivares, 42, the oldest daughter of Ivan Henry, was testifying Tuesday about the impact of her father’s 27 years of wrongful imprisonment on her life.

The North Vancouver child-care provider described a chaotic childhood in which her mother was a drug addict, creating “a lot of anxiety and constant worry” for her.

Her father would constantly get into fights with her mom, trying to make her sober, and was “very supportive” in a difficult family situation, she told B.C. Supreme Court Chief Justice Christopher Hinkson.

“My dad was just really there for us, I felt comfortable and stable with him there for us.”

All that changed in 1982, when she was nine years old. Henry was arrested and charged with sex offences against eight Vancouver women.

“From the moment we learned he was arrested, our world kind of crashed down on us,” said Olivares.

In 1983, a jury convicted Henry and he was declared a dangerous offender and jailed indefinitely. In 2009, he was released on bail after his case was reviewed and in 2010 acquitted after spending 27 years behind bars.

Olivares, a mother of two, told the judge that after Henry’s arrest, the neighbourhood kids would not talk to her and her sister Kari.

“So we basically were kind of hiding out inside our house. We couldn’t do too much.”

Then her mom went into rehab and she and Kari were taken away and put in foster care and the two sisters battled with sadness at not having a mom and dad around.

A year later their mother was reunited with them, but their chaotic childhood continued, with the family moving several dozen times.

Olivares said she has “very few” positive memories of life with her mother, who died in 1990.

“I probably had to save her life five or six times, from overdosing. I’d never know what I was coming home to.”

She periodically wrote to her father but did not see him for 12 years after his arrest and conviction.

“He wrote lots but my mom wouldn’t always give us his correspondence. After my mom died, I lost contact with my dad for several years.”

She did not share with her friends the fact that her father was in prison and she had no idea where he was actually incarcerated. To stop the questions, she told friends her dad was dead.

“I quickly realized if I said he was dead, that would end the questions. It was very easy that way.”

She knew that the charges against her father were “horrific” but she said she never believed them for a moment and started doing research and reading on her own.

She and her sister Kari started to really fight for their dad and wanted to get him out of prison, and they arranged for him to be transferred to a prison in B.C., where they could visit him.

“We felt he was innocent. It was so hard to watch him be there and ourselves be treated as criminals, to be searched.”

They would leave the prison visits in tears, she told the judge.

“It would take us a long time to recover from each visit. I couldn’t do it very often, I just couldn’t.”

After the criminal justice branch appointed a special prosecutor in 2006, Henry’s case was reviewed to determine whether there had been a miscarriage of justice. Evidence pointed to another suspect as being responsible for at least some of the attacks.

When her dad was released on bail in June 2009, Olivares and her family moved to a larger home so that they could accommodate Henry.

But it was to be a difficult transition for the man who’d spent much of his adult life behind bars.

When they picked him up from prison, he didn’t know how to get into the car or put on his seat belt.

“He was just on edge all the time. It was a really hard transition for him. It was hard for all of us.”

Henry was guarded and very insecure, constantly worrying that police were going to come and take him away again. He ate quickly and overate a lot. He’d get nightmares and tell his daughters he wanted to be returned to prison.

“We all tried to help make him feel comfortable and babystep him back to life. I feel I’m still helping him adjust to life.”

A family pet chihuahua became his saving grace and helped Henry through his difficulties.

At first some of the neighbours tried to get the family out of the neighbourhood but things improved over time.

Henry’s health became an issue.

“My sister and I were so scared he was going to have a heart attack.”

A visit from then-Attorney-General Mike de Jong, who came bearing a gift shot glass from France and apologies on behalf of the government, was welcome, said Olivares.

The whole ordeal — arrest, lengthy incarceration and now acquittal — has taken a toll on the family, she told the judge.

“I have to reassure my dad all the time that it’s going to come to an end. I’m constantly trying to reassure him. He’s tired, we all are.”

In January, tragedy struck as Kari overdosed on drugs. She’d always struggled with the loss of their father, said Olivares.

“She never recovered from the day he left. That’s the best way to describe it. My sister couldn’t get over it. She started battling alcohol and drug addiction herself.”

Henry is seeking compensation after alleging that the police were negligent in their investigation and the Crown had violated his rights by failing to provide proper disclosure prior to his trial. He is also alleging the federal government failed to provide a proper appeal for him.