She stands at the corner of Jefferson and 22nd Street, tall and a little stern, her red brick façade and stone steps heavy with the weight of 100 years of history.

Throughout that time, Ecole Pauline Johnson – the school known as PJ to many of its former students – has been more than a physical presence. Scout troops have met in the school, and what became the West Vancouver Youth Band was founded there in 1930. Gertrude Lawson, the daughter of community pioneer John Lawson, was one of her early teachers.

Her enrolment has ebbed and flowed over the decades. The school has also had some close calls, including a two-year closure in the mid 1980s when falling enrolment and budget cutbacks shuttered her doors and there was talk of letting the local arts council take over the building.

But the school has been resilient. Some of West Vancouver’s prominent citizens – including former West Vancouver schools superintendent Geoff Jopson and former mayor and MP Pamela Goldsmith-Jones – have been among her students.

In the case of some West Vancouver kids, “the front steps they sit on are exactly the same front steps their mothers and grandmothers sat on,” said Peter Miller, past president of the North Shore Heritage Preservation Society.

School opened in 1923

Pauline Johnson isn’t the oldest school in West Vancouver – Hollyburn Elementary, the first purpose-built school in West Van was established 10 years earlier.(Hollyburn was a significant step up from holding classes in a tent on John Lawson’s property, and from the next digs in a nearby church.)

But West Van was growing, and enrolment pressures there soon led to the need for another school.

Early concerns about school overcrowding balanced against high construction costs apparently weren’t so different in the 1920s than they are today, according to archival papers.

Originally approved as a two-room school on the current site, school trustees were soon voting to request additional money from the province that would allow them to build a slightly bigger school. The first bids on construction came in over budget.

A temporary three-room one-storey building first opened on the site in 1921, followed almost immediately by the addition of five more classrooms and a second storey in 1923, designed by local architect Hugh Hodgson. A newspaper article of the day noted the cost to build the school had been roughly $50,000.

By 1928, school trustees were grappling with enrolment in West Vancouver schools that was increasing at 15 per cent a year. Other additions followed.

At the time it was built the school would have been one of the largest – and certainly most imposing – buildings in the neighbourhood, said Miller.

The brick façade and solemn architecture carried a message, he added. “Education is important. Education is respected.”

PJ has stood through a century of change

The school took its name from the poet and performer Pauline Johnson, a woman of mixed Mohawk and Indigenous descent who was famous at the turn of the century for her depictions of Indigenous life and the author of The Legends of Vancouver from stories told to her by Squamish Nation Chief Joe Capilano.

Change has flowed around the school over the past century.

One former student Alan Turnbull wrote about listening to President Franklin Roosevelt’s ‘Day of Infamy’ speech in the Pauline Johnson gym in 1941.

He also met the girl he’d later marry at Pauline Johnson.

Newspaper accounts from the 1920s to 1960s gave accounts of the PTA meetings, Christmas concerts and staff changes at the school. The school loomed large in the community’s sense of itself.

In 1955, a newspaper noted authorities of the day had rejected a request by teachers to sell off part of the Pauline Johnson property for housing, with the thought that the land might be needed in the future.

In honour of the school’s centennial, former alumni were recently invited to share memories at an afternoon tea hosted at the school.

Several students who attended in the late 1940s and early 1950s recalled the pots of ink on their desks which they used for cursive writing.

Most of the area around the school was still bush and forest in those days, they said.

At recess and lunch, “You’d be racing through the woods the whole time,” one former student said. “In the morning I would ride my bike like mad, leaving home at 30th and Mathers so I could be pitcher when we played baseball before school started.”

School was “fairly strict,” said John Moir, who went to Pauline Johnson in the early 1950s. “They did give them the strap. It wasn’t a questioning time.”

His own parents moved from Vancouver to West Van in 1949, he said, partly because of the school. “The word was the schools were good and the taxes were low.”

“Of course you look in the classrooms now and there’s much more activity,” said another former student. “There’s much more engagement with learning. But I think we learned well.”

In the 1960s, the school experimented with what was known as “oral French” – which built 15-minute French sessions into the daily curriculum. It didn’t last, but it foreshadowed what was to come.

Dave Raglin, who went to Pauline Johnson in the early 1970s, said he and his five older siblings all attended the school. Later his nieces and nephews came to PJ. “Now I have a son here,” he said.

Raglin has fond memories of his time at the school. Half the teachers “scared the hell out of us,” he said, while most were “wonderful.”

Outside of the school building itself, playgrounds in his day contained many thrilling pieces of play equipment that would now be considered dangerous, he said. One involved running around on the end of a chain until you were airborne. There was also a high metal slide that would burn your rear end in summer and “if you fell off you fell on to pavement.”

Back then, “everyone seemed to live within walking distance,” he said. “There was no getting a ride to school, ever.”

Pauline Johnson’s enrolment continued to swell in the post-war years when families settled in West Vancouver, reaching over 600 in the early 1960s.

Re-invention as French Immersion school

But in the 1970s and '80s the pattern reversed. By the early 1980s the number of students had dropped to 200. Pauline Johnson was closed, along with four other West Vancouver schools, amid declining enrolment and provincial budget cutbacks.

PJ was down, but not out, though. Two years later, in 1985, the school re-opened as a French Immersion school. The school’s popularity has grown ever since, attracting students from all over the Lower Mainland. Enrolment today sits at 423, making it one of the largest elementary schools in West Van, and it offers both early and late French Immersion.

The school uses a lottery system to decide which families get to enrol their kids in kindergarten, said Tara Zielinski, the current principal. “We generally have well over 100 applicants” for 40 to 60 spots, she said. Those who live in West Vancouver and have siblings at the school get first dibs.

Not surprisingly, there have been changes to the school over the years.

A major renovation that preserved the school’s exterior façade and other heritage features was completed in the 1990s. Further upgrades to exterior walls and windows were completed about 10 years ago. These days, two portables also provide overflow classroom space, while another two provide space for childcare.

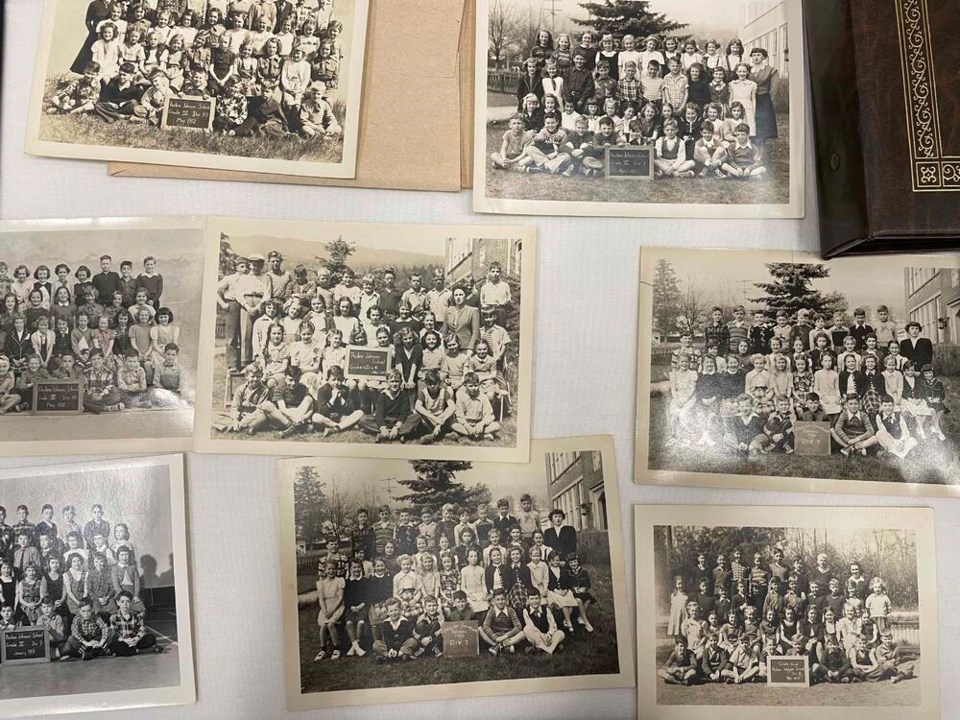

Inside, the tall windows spill bright light into the classrooms and a glimpse of leafy trees outside. Tucked away on one wall, former school photos march back through the decades.

Zielinski says one of her joys as principal is seeing what the school meant to past generations. Former students still sometimes drop by to visit.

Said Raglin, “It was a really warm community feeling here.”