The woodworking shop at the West Vancouver Seniors Centre is a busy place on a Tuesday morning.

Here, amid the wood dust and the sound of saws and sanders, Audrey Viken, 81, is making delicate jewelry boxes out of pieces of driftwood.

Derrick Leeson, 91, is also a regular volunteer at the seniors’ woodworking shop. “I used to teach five classes a week” at the centre, he says. Leeson still puts in long hours in the spring, getting electronics ready for sale in the centre’s fundraising flea market.

Both are among about 4,000 active members at the centre, who range in age from 55 to 102 and are redefining the nature of getting older.

“We’re certainly more active and more interested in keeping ourselves healthy” than past generations of seniors, says Viken.

One biking group, including many members in their mid-70s, went for a bike ride to Steveston and back earlier in the week.

“They are living fitter and more active lives than many people in their 20s,” says Jill Lawlor, seniors services manager with the District of West Vancouver.

The seniors are also part of a grey wave that is forming an increasing segment of the North Shore’s population.

To perhaps nobody’s surprise, the latest statistics from the 2016 census show the North Shore is getting older, along with the rest of B.C.’s population.

Statistics on population age groups, released May 3 by Statistics Canada, showed the population aged 65 and older grew more rapidly than younger generations throughout the North Shore.

In West Vancouver, the “oldest” of the North Shore communities, people 65 and over now make up almost 28 per cent of the total population.

That’s significant, although it pales in comparison to some B.C. communities.

In Qualicum Beach, for instance, 52 per cent of the population is now 65 or older. In B.C. as a whole, 18 per cent of the population is in their “golden years.”

According to the 2016 census, the number of people 65 and older in West Vancouver is up more than eight per cent since the last census in 2011.

Numbers of those over 85, like Leeson, are up even more – by 14 per cent. That’s at a time when West Vancouver’s overall population is actually shrinking.

The story is similar in North Vancouver, where the numbers of those aged 65 and older grew by more than 14 per cent in the district in the five years between 2011 and 2016, and numbers of those over 85 grew by 20 per cent. That’s at a time when the number of working-age people 15 to 64 was contracting.

Even in the City of North Vancouver, where the number of children under 14 increased by eight per cent between 2011 and 2016, the number of seniors grew at twice that rate – increasing by almost 27 per cent.

Even numbers of the very oldest citizens are impressive. According to the census figures, in 2016, the North Shore was home to no fewer than 60 people aged 100 or older. Five out of six of those centenarians were women.

While the number of seniors is up – a statistic created both by longer lifespans and by the fact the baby boomers have now reached retirement – other segments of the population on the North Shore are noticeably smaller.

Those aged 25 to 35 make up one of the smallest parts of the population in the districts of both North Vancouver and West Vancouver, clocking in at under six per cent of the total in West Vancouver and under nine per cent in the District of North Vancouver (they are slightly better represented in the City of North Vancouver.)

“I think that continues to be quite a pronounced gap,” said District of North Vancouver Mayor Richard Walton.

The key to getting that “missing generation” back on the North Shore is affordable housing that meets the needs of young people, said Walton.

Walton said increasingly, people who commute from other areas of the Lower Mainland are filling jobs on the North Shore.

He said statistics show it isn’t untrammelled growth on the North Shore that is contributing to traffic gridlock, as some people believe – because the number of working people aged 15 to 64 living in both districts of North Vancouver and West Vancouver shrank between 2011 and 2016.

“It’s really about regional growth,” he said.

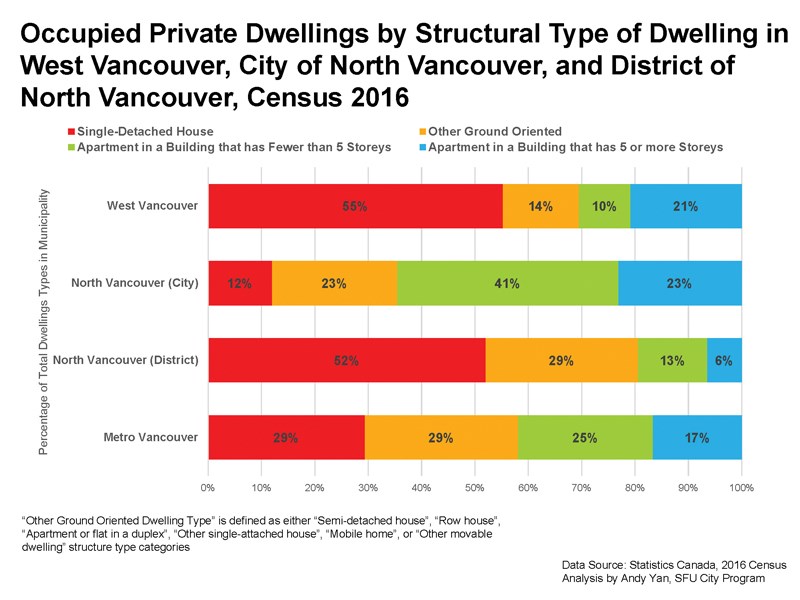

The other statistic released from the census – on dwelling type – showed some significant differences between the two more suburban North Shore districts and the more densely populated City of North Vancouver.

Single-family homes are still the dominant type of housing in West Vancouver – accounting for 55 per cent of all dwellings there – and the District of North Vancouver – where 52 per cent of homes are single-family houses.

In the City of North Vancouver, however, single-family homes make up only 12 per cent of dwellings, while 64 per cent of residents live in apartments.

“I was actually quite surprised,” said Andy Yan, a professor of urban studies and regional planning at Simon Fraser University, who studies housing trends in the Lower Mainland.

The City of North Vancouver, in fact, has one of the lowest percentages of single-family homes in the region, second only to the University of British Columbia endowment lands, said Yan.

“There is a larger diversity and complexity in terms of how people live than you might expect.”

While the number of single-family homes in the District of North Vancouver is still high, that percentage of the total is gradually falling, said Walton, adding when he first took office as mayor, about 57 per cent of dwellings in the district were single-family homes.

The goal of the district is to lower that figure further – by adding additional types of housing – so single-family homes only make up about 44 per cent of the total by 2030.