It is a cold, drizzly Thursday afternoon, and Sḵwx̱wú7mesh (Squamish) Elder Sam George is reclined in his favourite armchair, taking refuge from the rain in his home on the Eslhá7an (Mission 1) Reserve on the shores of Mosquito Creek.

His demeanour is calm and composed. His manner of speaking is polite and friendly, his voice soft. In conversation, he is quick-witted and playful, offering brief glimmers of humour despite the sombre subject matter.

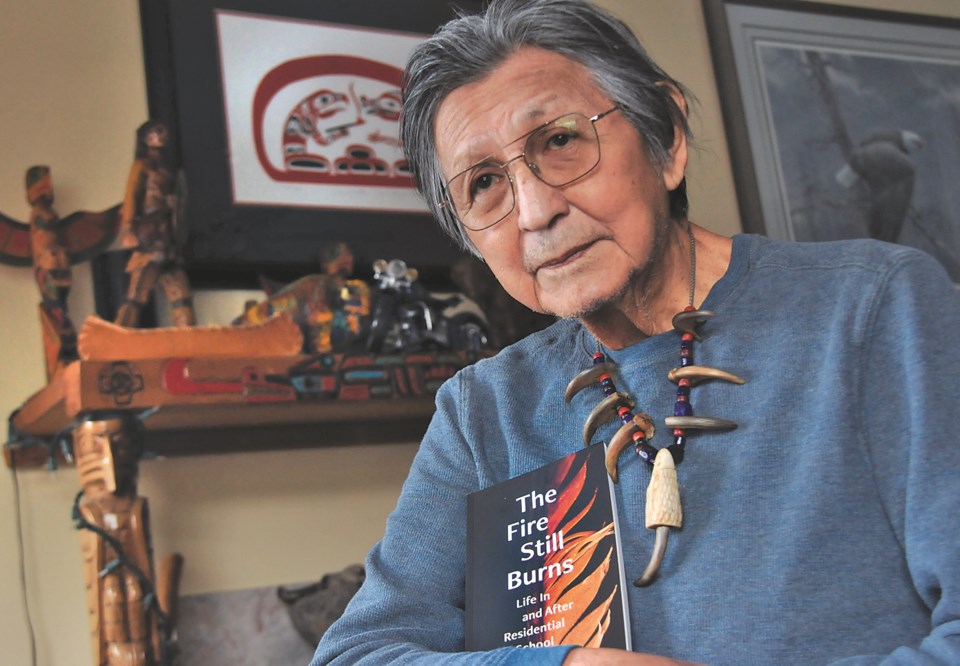

George, who also goes by the Coast Salish name Tseatsultux, is discussing his memoir, The Fire Still Burns: Life In and After Residential School, an unflinchingly honest account of his time at St. Paul’s Indian Residential School in North Vancouver.

The book, due to be released in May, details a childhood fraught with emotional, physical and sexual abuse, and a life after, marred by addiction, family violence and imprisonment.

“I want people to understand why my generation is the way that it is,” says George, bringing his hands across his lap and putting them together in a gentle clasp.

“Like a lot of people from my generation, I had eight years of residential school, four and a half years in prison, and I never learned a thing. Right after prison there was drinking and drugs. I’ve been married five times. I’ve been abusive. But I’ve turned my life around, and others can too.”

George’s quietude might seem incongruous in the context of such heavy conversation, but the Elder says he has become accustomed to recounting his story to strangers.

Besides, the bulk of this book was typed long ago, he adds, a byproduct of an act of catharsis that had been sitting on his dresser in his home for years.

It hadn't been until George came into contact with Jill Yonit Goldberg, a writer and college instructor, that he considered it might be worthy of being published.

Goldberg teaches a class at Langara College that pairs students with members of the Residential School Survivors Society to write their memoirs. George’s already written pages struck a chord with Goldberg and the three students he was paired with, Liam Belson, Dylan MacPhee and Tanis Wilson. The idea was floated of expanding his self-written words into a fully fledged book.

Thus began a year of in depth interviews to secure the finer details of his life story – and no stone was left unturned. George describes thoroughly his idyllic childhood growing up on the Mission 1 Reserve: Days dedicated to smoking salmon and collecting berries, pears and plums, and weekends spent celebrating and drumming with hundreds of community members in the Longhouse.

The school years

He recollects the first day of his school experience with ease, fragments of that memory as vivid now as when they were first imprinted on his mind. A tall, white, “strange man” knocking at the door, the tear-filled eyes of his mother, the solemn, silent walk four blocks from his old home to his new.

From here George enters a place where arcane rules govern every aspect of his life, from the clothes on his back to the food in his mouth. His hair is shaved and his ancestral name forbidden. Enduring the strap, a foot long piece of leather or rubber, becomes a quotidian event, as does sexual abuse, when a particularly malevolent nun forces him to become her “plaything” for two, long years.

These fragments of childhood trauma are seen through the lens of George's mind as it is now, quiet and accepting. He relays the harrowing events that shaped his childhood with straight-forward precision, and without a trace of self-pity or request of condolence from readers.

His adult years are written with the same unvarnished truth, not seeking sympathy, respect or even condemnation, simply laying out the facts as they happened.

He describes a knife attack carried out on his own brother, a violent outburst that would land him in Oakalla Prison for attempted manslaughter. He talks of the family violence he inflicted at home on his partners and his children. During one chapter he explains how he once had thoughts of killing his own wife when in a state of drug-fuelled psychosis.

It is easy to wonder whether George had always intended on being so brutally honest, on both his own wrongdoings and the wrongs that had been done to him. Had there ever been a point, during the book’s preliminary interviews or its writing, where he had considered withholding certain aspects of his story? Not least to protect his own image?

“Never. You know what, I just thought I had to get it out, as honestly as possible ... this is how it is – this is what happened,” he says.

“From my generation, a lot of the people I knew were very dysfunctional. Alcoholism. Drug addiction. A lot of us were in jail. If we had been married, we were then separated. So many are still pulling themselves together, climbing out of that.”

George says he hopes his searing honesty will help others who might have endured similar experiences, had the same thoughts, made the same mistakes.

“Somewhere, somehow, I hope they can pick up the book and say ‘I remember him’, and ‘if he can do it I can do it.’ Because I do feel as though I’ve come a long way.”

At least 4,000 children's lives claimed

George’s story is like that of so many others who attended St. Paul’s Residential School during its years of operation between 1899 and 1958, and the other 130 or so schools that operated across Canada between the 1880s and the 1990s.

While the schools offered some cursory education, their real incentive was to remove and isolate children from their culture, ancestry and traditions, and to assimilate them into Western society. Children were forcibly removed from their family homes, their hair was cut short, their traditional clothes stripped, and their names replaced by a number.

Physical and sexual abuse was rampant, disease and malnourishment common.

According to the National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation, over 4,000 children died at residential schools, although unmarked graves and lack of records make it difficult to pinpoint the true number of children who never made it home.

Over 2,000 children were institutionalized at St. Paul’s, one of 18 schools in B.C. and the only one in Metro Vancouver. According to public records, 12 unidentified students died while in attendance, while others were relocated to Kamloops Indian Residential School – where the remains of as many as 215 children were confirmed in 2021.

George still thinks about the friends who disappeared during his time at St. Paul’s, the questions left unanswered.

There was Pearl, a girl no older than fourteen who disappeared without a trace. There was Charlie, a little boy of three years old who lost his life at the hands of the nuns. He still thinks about the four foot long, three foot deep hole he and his brother, Andy, were instructed to dig in the school’s garden. Had it been a grave for a classmate?

The healing process

For a long time George says he “couldn’t stand” the priests and the nuns associated with the school, the Catholic Church at all. In recent years, however, he says his anger has subsided.

"Now I look at nuns and priests who are around and just say, 'OK, these weren’t even around then. They probably weren’t even born,'" he says with a laugh.

“You know what I had to learn? I had to let it go. It happened. That’s the past. Don’t pack it around any more, although I didn’t know I was doing that at the time. I was letting the past control me. There was a lot of anger and resentment, a lot of pain, a lot of feeling sorry for myself. Once I looked at it all and realized it all, then I realized I could change it.”

Now George is focusing his energy on rebuilding relationships with his family. He smiles when he talks of his sons, aged 55 and 50, and how they now see each other regularly, often bonding over breakfast outings. He radiates pride when conversation pans to his granddaughter, a Squamish language teacher fluent in their native tongue.

As the rain continues to patter on the window of George's home, he takes a moment of quiet to ponder the Truth and Reconciliation Act and the annual date dedicated to residential school survivors. Reconciliation, he says, is a word that is tough to put meaning to.

He is dubious of the movement, because for reconciliation to occur, “Canadians should know that the residential school system happened” and education isn't yet where it should be.

It's why he is pushing for books like his own to be included in curricula the country over, and why both he and Goldberg ensured there was a reader's guide in its final pages, with questions that encourage students to understand his writing in a cultural, social, psychological and historical context.

For now George, now almost 80, will continue to plow on with his own way of enforcing education. He continues to work as a drug and alcohol counsellor, using his own tale of addiction and sobriety to show others they can turn their lives around too.

In his role as an Elder he travels across the city retelling his story in schools and at public events, so communities outside of his own can better understand the pervasive impacts colonization and the residential school system continue to have on Indigenous people.

"I'm able to tell my story" he says with a faint smile, "and not many people have been lucky enough to say that."

Mina Kerr-Lazenby is the North Shore News’ Indigenous and civic affairs reporter. This reporting beat is made possible by the Local Journalism Initiative.