Born Wearing Crampons: John Clarke: Explorer of the Coast Mountains, Centennial Theatre, Saturday, Nov. 17, 7: 30 p.m. (doors 6: 30 p.m.). For more details vimff.org.

MOUNTAINS were "absolute unity in the midst of eternal change" for Thomas Wolfe; for Anatoli Boukreev, they were the cathedrals where he practised his religion, but for B.C.'s greatest and most prolific mountaineer, mountains were also the place where, sometimes, wolverines ate your food.

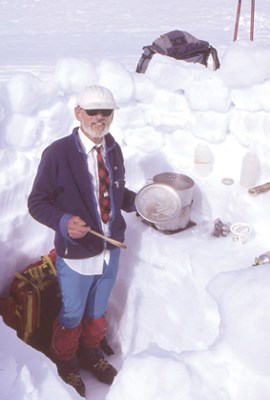

John Clarke's astonishing number of first ascents, his contributions to conservation, and his tangles with wolverine slobber are chronicled in the new book John Clarke: Explorer of the Coast Mountains, by Lisa Baile.

Baile, a medical researcher from England and a friend of Clarke's, seems an unlikely candidate for a mountain climber.

"I grew up in the flatlands of Lincolnshire on a farm. Actually it's even below sea level," she notes. "I had absolutely no idea that one day my passion would be mountain climbing."

Baile was briefly introduced to mountain climbing when she strayed from her group of Quebec bird watchers, but upon moving to British Columbia she was powerless to resist the rocky terrain.

"The mountains are inescapable. They're right at your doorstep," she says. "I got smitten by the mountains and never looked back. . . . Then of course, once you're in the mountains there's no escaping John Clarke. He was legendary even in his own time among the mountaineering community."

Born in 1945, Clarke devoted himself to mountain climbing when he was still in his teens.

"Most people go on single trips, for John it was a lifestyle. He did seasons in the mountains, he spent five or six months a year in the mountains. He lived there. He was on the mountains on their own terms," Baile says. "He spent the next 40 years out there."

Much like winter winds blow migratory birds south, the first snows of the season would send Clarke down the mountain to eager friends and the relative drudgery of employment.

"He had a huge variety of jobs," Baile says. "The main criteria was it would finish in mid-April."

Clarke worked at a sawmill, a glass company, and an auction house, but with each spring thaw he headed back to his mountains.

"He'd always start from tideline and then make his way up to the alpine, and then traverse the ridges, try not to go down into the valley, and do these long, long traverses," Baile says.

Many of those traverses were done alone.

"He was extremely, extremely careful. He did go on his own, which is a no-no in the mountaineering community, you're never supposed to go on your own, but for him it was a question of, 'Well, I go on my own or I don't go,'" Clarke says. "He would always say, 'If there has to be an injury, please, please make it from the waist up.'"

Making that long trek into the cold, thin air while shouldering an enormous backpack and eating food dropped from helicopters and floatplanes would seem to have a limited appeal, but for climbers like Baile, it's the re-awakening of something both primal and pure.

"For me, it's extraordinarily beautiful. It's a re-connection with nature. It's like nothing else I've ever experienced. You're out there, you're alone, and the longer you're out there the closer you get to what it used to be like for people," she says. "It's not just about getting to the peak. It's the journey."

While many mountaineers hunt for those select peaks that tear jagged holes in the substratosphere, Clarke explored entire mountain ranges, adding texture and context to B.C. geography.

"John was very different from a lot of the mainstream mountaineers in that he wasn't interested in trophy climbs or big peaks. What he wanted to do was fill the gaps in the mountains that hadn't been climbed in the coast range," Baile says

Clarke and Baile bonded when the duo co-founded the Wilderness Education Program, a project designed to help young people connect with nature.

The two became friends and it wasn't long before Clarke's equipment filled Baile's home and his stories came alive in her kitchen.

"He became one of the family very soon. In fact he would often stay over at night and in the evening he would show up for supper and of course there were these fantastic conversations at the dinner table and he would regale us with stories," Baile says. "It was magic. I remember saying, 'John, you should write a book.' And of course he'd say, 'Oh no, John Baldwin writes books, I don't write books.'"

Clarke became a father in 2002. That same year, he was diagnosed with a malignant brain tumour.

After Clarke's death in 2003, Baile was steadfast that her friend should be remembered, not just for what he did, but for who he was.

"I think his most amazing thing was how he could connect with people. Almost to me, more amazing than all those 600 first ascents he made. Didn't matter what age somebody was, whether they were two years old, 90 years old, he had that ability to connect with people, and he made them feel special," she says.

Recording Clarke's days of avoiding avalanches, threading through crevasses and subsisting on porridge and tea ultimately fell to Baile.

"It wasn't till after John died I had this idea in the back of my head that somebody would write a book but hell, I didn't write books. I did science," she says. "But gradually I realized I know John's family, I know the mountaineering community. I have connections with a lot of his friends, conservationists, environmentalists and so on. So, maybe."

Writing the book was accompanied with tinges of regret, according to Baile.

"I realized, 'Why didn't I ask him more questions? Why didn't I put a microphone under the dinner table?'" she says.

Besides serving as a monument to an explorer, Baile says the book is also a letter to Clarke's son. "John has a son, Nicholas, who is now 10 years old. And a lot of these stories I know John would want to be passed on to his son. . . . I hope this book will circulate John Clarke to the world, because he's a pretty special person and it's not just for his mountaineering endeavours. He taught enduring truths about life, and everybody will find something in this book to take away. And mainly it's realizing your own dreams."