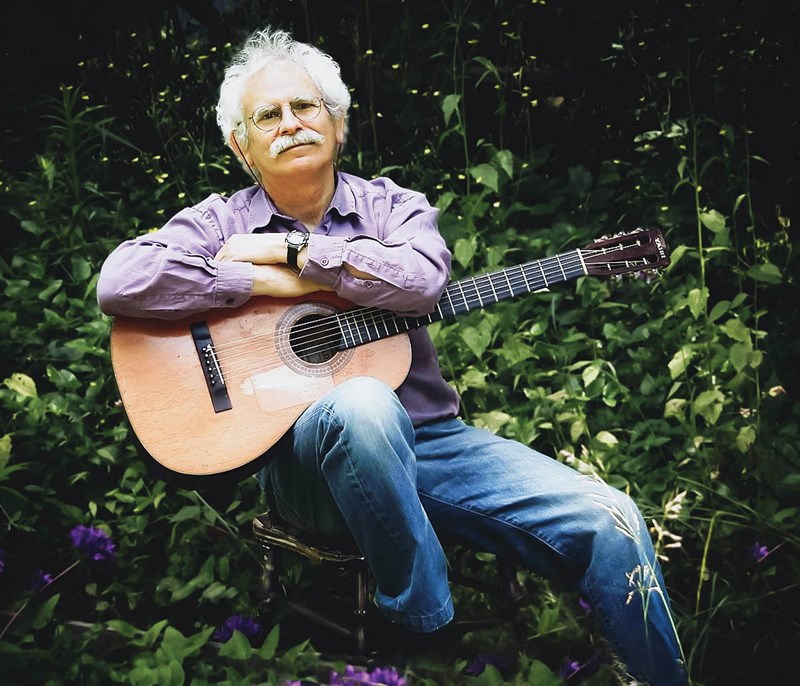

Bob Bossin, Vancouver Folk Music Festival, until July 16 in Jericho Beach Park (thefestival.bc.ca).

Bob Bossin generally avoided calling Pete Seeger.

“I’m Canadian,” Bossin explains apologetically, which explains it all.

Burdened with folk legend status, Seeger was often inundated with well-wishing-would-be Woody Guthries. He and Bossin had played music and cleaned up litter together (there was time to spare in Philadelphia) but Bossin was still reluctant to add to his friend’s burden.

But about six months before Seeger died, Bossin overcame his Canadianess.

Seeger’s granddaughter answered the phone.

“Does he know you?”

“I’m an old friend,” Bossin replied.

Recognizing how lame that sounded, he added: “He used to sing one of my songs.”

“What song was that?”

“Oh, it was a long time ago,” Bossin replied, his mind drifting to a bawdy 1975 tune in which an unrepentant high school student responds to a pitch for beauty pageant contestants by asking the recruiter to display a particular body part.

It seemed a long way from “Where Have All the Flowers Gone?” but it appealed to Seeger.

“It was a song called ‘Show Us the Length,’” Bossin told her.

“He sang that last month!” she said.

Seeger introduced Bossin’s song by saying: “It was by this guy up in Canada.”

But he couldn’t remember Bossin’s name.

Bossin’s journey to become “this guy up in Canada” began in the 1950s when he was struck by the first wave of rock ‘n’ roll – and its demise.

“It was sexy in a way that when I was nine or 10, I wouldn’t have understood, but something grabbed me.”

It was in the throes of that first rush of rock ‘n’ roll that Bossin asked his parents for a guitar.

“They gave it to me, saying ‘You’ll never stick with it.’ Which is the only reason I did.”

But then something changed.

Elvis was in the army, Chuck Berry in jail, Jerry Lee Lewis shamed into a pseudonym, and Little Richard too religious to chronicle about the mating rituals of Miss Molly.

From his home in Toronto, Bossin watched as an invisible hand dipped America’s raw-edged rhythm and blues into a sterilizing solution.

“Rock ‘n’ roll got really kind of insipid as the music industry took over,” he says, singing a couple bars of “16 Candles” to make his point.

But there is perhaps no creature so attuned to interesting frequencies as a bored child, and so Bossin was receptive when he heard a voice that sounded like it was coming from the bottom of a well.

That voice and a lonely guitar drifted out of WGR radio in Buffalo.

“They played the damnedest song I’d ever heard in my life.”

It was the Kingston Trio singing “Tom Dooley.” It wasn’t the way they played (“not particularly well, in hindsight”). It was the grisly story and all the possibility it suggested.

There was murder and retribution. There was history. The people in these songs had jobs. And it felt true.

“I could feel real people who cared about their music and weren’t doing it to make the next hit song,” he says. “I stuck with it and I’ve stuck with it my whole life.”

There’s an old quote, sometimes attributed to singer Utah Phillips, that if a folk singer is successful he can make “hundreds of dollars.”

Bossin seemed close to commercial success a time or two in his 45 years of playing, writing, recording and touring.

His winking tribute to a former prime minister, “Dief Will Be the Chief Again,” performed by Bossin’s group Stringband, was played on CBC radio.

A CBC announcer heard a hit, but the verdict from a record company was: “Too Canadian.”

And while any song that likens love to a Jehovah’s witness banging on the door should be a hit, “Shirley Ann” wasn’t.

But while Bossin has escaped the tentacles of the Top 40, his career is notable for a different kind of success.

With forestry company MacMillan Bloedel set to log a huge sweep of Clayoquot Sound’s temperate rainforest, Bossin wrote a song.

He sang “Sulphur Passage” on a logging road, “standing on a stage made of a sheet of plywood lashed to the top of a VW van.”

As arrests piled up, many protesters changed tactics, opting to target MacMillan Bloedel’s customers. They warned of major protests and – unbeknownst to Bossin – showed “Sulphur Passage” along with a video about clearcutting.

“So I figure I saved Clayoquot Sound. I had help, of course,” Bossin notes, thanking the director, editor and fellow musicians who made it all possible.

More recently, Bossin targeted the Kinder Morgan Trans Mountain pipeline expansion with a YouTube video entitled: Only One Bear in a Hundred Bites, But They Don’t Come in Order.

It could have been a song, he allows, but instead, he wanted it to be a speech, alerting people to the dangers of tank farms.

“I like to think I had a little hand – or at least a finger – involved in defeating Christy Clark,” he says, noting more than 12,000 viewers have watched the clip.

For Bossin, singing about what people are talking and thinking about is success. That’s what folk music is, he says, explaining that the designation: professional folk singer is “kind of a contradiction in terms.”

Asked why people should see his performance, Bossin laughs, sounding like he just stepped out of a Mordecai Richler book.

“I’m old, I’m gonna die soon. They should be there when they can or they’ll be sorry!”