Michael Zemcov is thinking about inflation and the pipeline – but his ruminations don’t have a thing to do with money or oil.

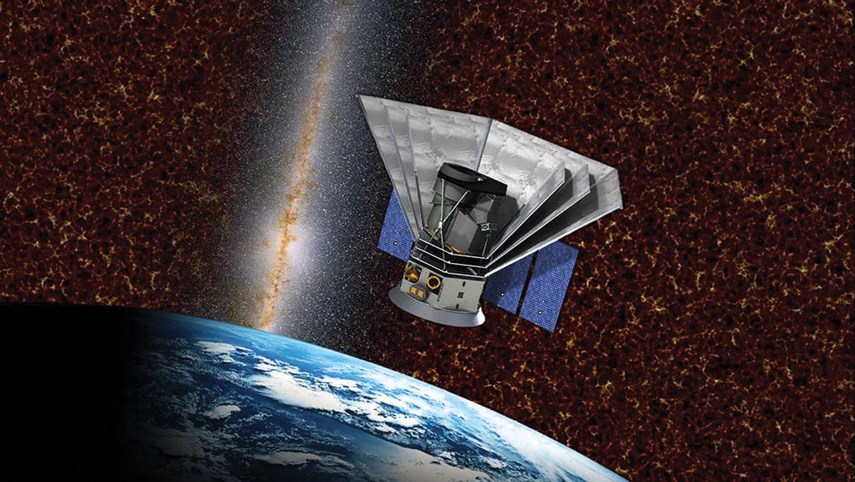

In 2023, NASA is set to shine its high beams into the cosmos. The space agency’s two-year, $242-million mission has a goal of surveying 300 million galaxies and drawing a map of the sky in 96 different colour bands, essentially bringing the world’s biggest box of crayons to an indescribably awesome canvas. The mission is called the Spectro-Photometer for the History of the Universe, Epoch of Reionization and Ices Explorer, or SPHEREx.

But before we can see those Universal pictures in hi-def, streams of galactic data will flow back to Earth. And there, an enthusiastic Handsworth grad will be waiting.

For Zemcov, the fact finding mission began when he was a kid poring over accounts of Tang and the Milky Way in National Geographic.

“I was very interested in space as a little boy,” he says.

As a student he was lazy and prone to daydreams, he recalls. Both his parents were microbiologists, which inspired his own form of youthful, scientific rebellion.

“I had this idea in my head that I would do anything that wasn’t microbiology,” he laughs.

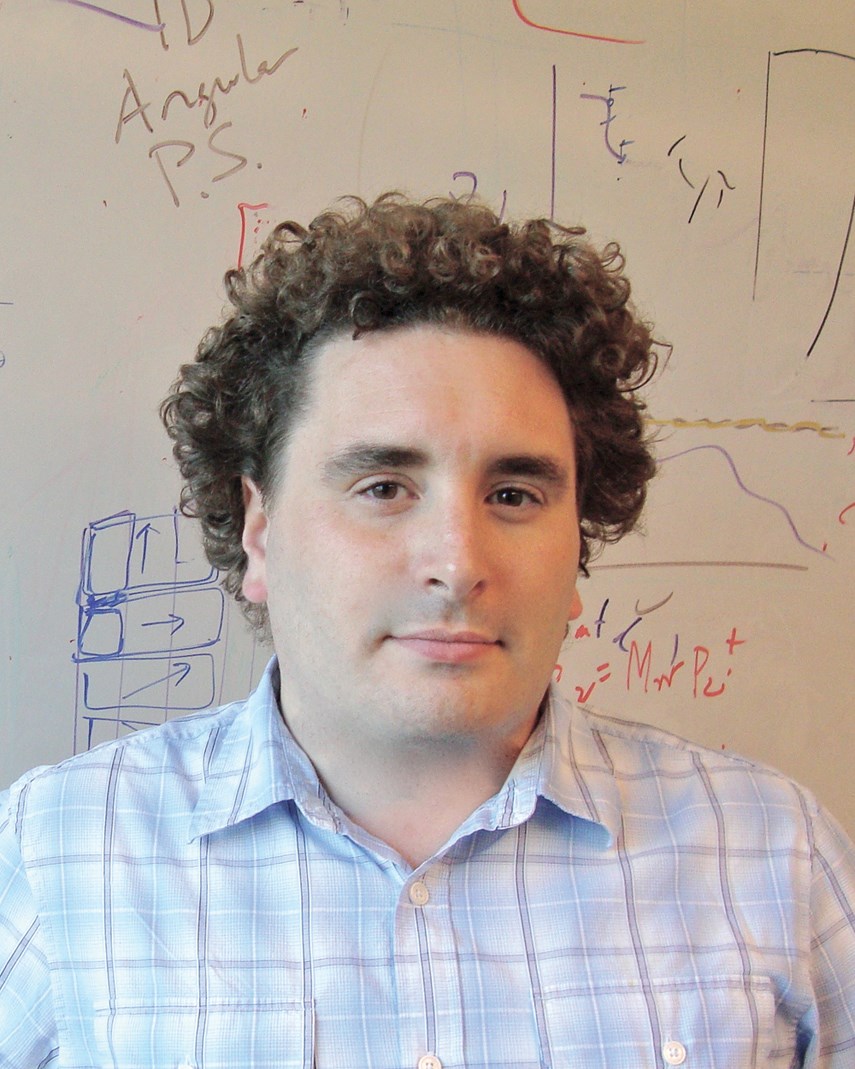

Zemcov currently works as a professor at the Rochester Institute of Technology in New York. And while Handsworth is nearly 4,500 kilometres away, the school was an essential part of his journey.

“Canada, unlike where I live now, really places a value on educating everybody.”

As a teen Zemcov had an aptitude for science and math as well as an innate fascination with the mysteries of the universe.

“I really just followed things that were interesting and I asked questions I found interesting to pursue,” he offers. While the material is complex, his rationale is disarmingly simple: “I can teach you physics but I can’t teach you enthusiasm.”

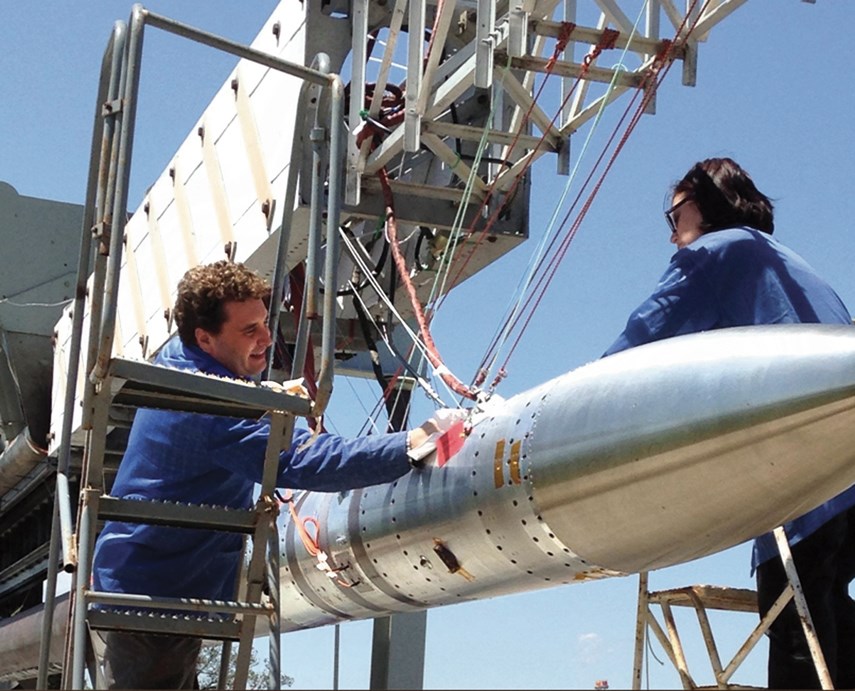

Mentored by UBC experimental cosmology professor Mark Halpern, Zemcov found a place for his passion in the riddles of the stars and the light between them.

“It’s come out that the universe we live in is really weird,” he says. “What is dark matter? Why is there so much of it?”

Fundamental physics offered ideas but not answers, Zemcov says. But SPHEREx might.

Every six months, the spacecraft will survey the entire sky. The technology is adapted from Earth satellites and Mars spacecraft but functionally it’s a bit like training your cellphone camera on the scenery outside your car window. And instead of blurring or an extreme close-up of the careless photographer’s thumb, the SPHEREx images can be marred by sensitivity to photons or less than uniform detectors.

“You kind of have to undo all that to get back and what the detector actually sees,” Zemcov says.

The information from the spacecraft creates what Zemcov calls a “firehose of data.”

In order to get scientific sense from that deluge, Zemcov is one of the planners of an information pipeline. There must be quality control at every step, he says, as well as assurance that an error can be detected at any of those steps.

“If you make a little mistake at the top of the pipeline, how does that propagate down through the whole thing?” he asks.

Once scientists can be sure that what’s coming out of the pipeline is safe to consume, they’re free to focus on inflation – the expansion of our universe in the “tiny fraction of a second” following the Big Bang.

The Big Bang is the best explanation for the reason the universe, like most shopping malls, looks the same in every direction.

“The problem is, we don’t really have any direct proof,” Zemcov says.

While we’ll never have an eyewitness account, SPHEREx can build a three-dimensional map of the universe. We can see space when it was young and study the “little seeds of galaxies” before they took root.

In some ways, the project is like looking at the tag at the back of your shirt or figuring out why your car stopped squeaking when you brought it to the mechanic.

“What is the universe made of?” Zemcov asks. “Why did it do that?”

SPHEREx is an attempt to chronicle the odysseys of light and stars in the same way anthropologists study the movement of human beings. But it may also have ramifications on the future.

They’ll be searching for water ice around young stars, Zemcov says.

“Where does water live when you have a young star that’s forming planets?” he asks. “That’s kind of an interesting question if we’re going to search for life.”