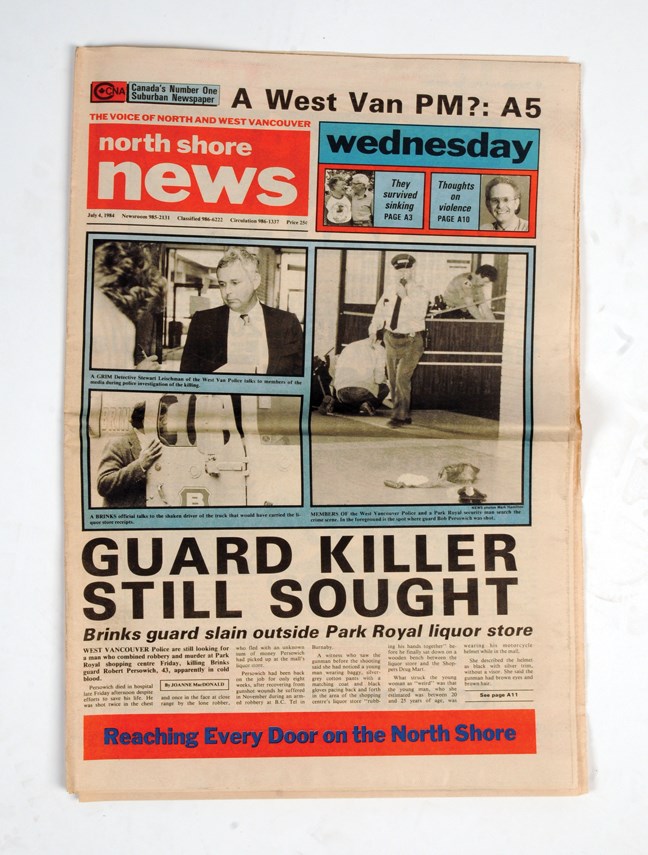

Robert Persowich had been back at work for less than two months when a man in a motorcycle helmet shot and killed him outside the liquor store in Park Royal South.

It was June 29, 1984.

Perowich was a guard for Brinks Canada. He lived in Port Moody with his wife Kay and their two children.

He’d been shot before. In November 1983 he’d been delivering cash to the B.C. Telephone Co. head office in Burnaby when he was robbed and shot in the stomach.

He spent six months recovering. He underwent two operations. And then he went back to work.

He had trouble sleeping at night, Kay told the Lethbridge Herald.

“Bob dreamed that he was being shot over and over,” she said. “They were horrible dreams.”

Brinks offered him an office job. Safe but boring. He turned it down.

And so, at about 5 p.m. on the Friday before the Canada Day long weekend, Persowich was holding the day’s take from the liquor store when a murderer hopped off the bench by Shoppers Drug Mart and shot three times with a .38.

Persowich died that day. He was 43.

Surf, turf and art of BS

West Vancouver used to be a sleepy little town, reflects retired detective Stuart Leishman.

“After one or two in the morning you could fire a cannon down Marine Drive and not hit anybody,” he says, sipping a cup of tea at a North Van coffee shop.

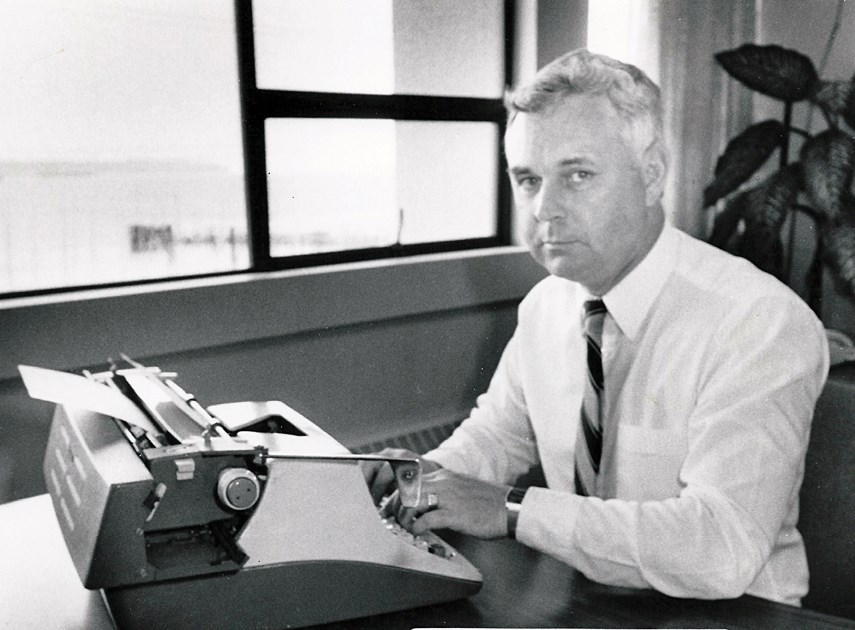

Leishman, now 72, joined the West Vancouver Police Department in 1973. And in the decade before the Park Royal murder the Yorkshire, England-born detective dealt with drug dealers and “youth problems” like drinking on the beach. But major crimes, he notes, “were quite few and far between.”

It was a different time.

It was a time when, if a skunk inexplicably crawled inside your clothes dryer, not only would the police take the call – they’d head to the British Properties armed with a plank of wood and a strip of bacon in order to protect you, the skunk, and your next load of whites.

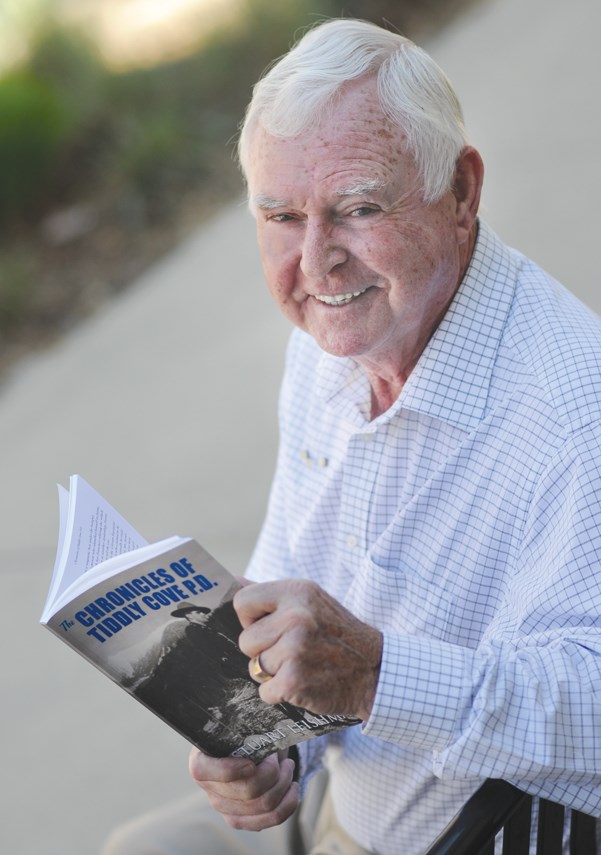

Leishman describes that largely vanished West Vancouver in his self-published book The Chronicles of Tiddly Cove P.D.

The book starts with Leishman heading to Ambleside Beach to wrestle runaway steer after a succession of cattle hopped off a barge bound for Vancouver in 1976.

“After the first one ‘jumped ship,’ the rest thought this was a good idea and all the cattle followed!” he writes.

The beach filled with the curious and pyjama clad as the young constable walked along the sand, soothing with his new cow friend. It was fairly calm until a North Shore News shutterbug took a flash photograph.

“When the flash went off, so did the steer,” he writes.

Leishman threw his arms around the cow’s neck and dug his heels into the sand.

“I managed to wrestle it to the ground but it was fighting to get back up.”

Eventually, the sedated animal collapsed on the beach. That’s when the tide started coming in.

With the fire department on the scene, the amateur cowboys wedged a sheet of plywood under the steer and dragged the animal to the high tide mark.

It was 5 a.m. and Leishman, soaked with saltwater, waited by the cattle until the owner arrived.

Writing for the Vancouver Courier, Grant Lawrence recalls his father, Garth, getting the following message from West Van police at 2 a.m. “We have two of your cows down on West Bay Beach and we’re going to have to shoot them to avoid further potential property damage.”

Not wanting dead cows or property damage, Lawrence picked up the cows that morning.

For his part, Leishman was moved, but not changed.

“It was difficult not to think of my new friend for the next little while when I ordered a cheeseburger,” he writes before adding: “I got over it!”

Some of the most important tutelage of Leishman’s career came from Jack Ross.

Ross, a sergeant at the time, took the 140-pound rookie on a call to Horseshoe Bay to deal with motorcycle gang the 101 Knights, Leishman writes.

They got to the terminal and found: “20 hairy leather clad goons gathered around their Harley Davidsons” and another half-dozen racing motorcycles in the parking lot, he recalls.

Ross confronted the leader of the pack. At the time, Horseshoe Bay was a dead spot in terms of radio contact with the police office, Leishman writes. Leishman also notes that every other officer on duty at the time was tied up executing a search warrant at a Marine Drive hotel.

The two cops were on their lonesome.

Ross, nonetheless, told the bikers they had a group of officers waiting at the top of the hill and that if the bikers didn’t settle down: “We would kick some ass!”

It worked.

“They settled down and meekly waited in line until the ferry left,” Leishman writes.

Driving back to the station, Ross explained his take on psychological warfare, (slightly edited for the newspaper): BS baffles brains.

It was a credo Leishman took to heart.

June 29, 1984

Leishman was looking forward to a weekend with his family when the phone rang.

A guard had been shot and robbed.

The killer ran to the rooftop parking lot, took off on a motorcycle and left behind a description as as frustrating as it was vague. He was 5-10, 160 pounds, and wearing a full face motorcycle helmet.

Leishman called his wife and told her to expect him when she saw him.

“This stage of a major investigation is an exercise in organized confusion,” he writes.

With personal computers still in their infancy (Apple had unveiled their first Macintosh in January) Leishman logged every bit of evidence into a ledger book and crammed boxes full of documents.

After working through the night, his partner, detective Colin McKay, grabbed a couple hours sleep in an empty cell before starting the day shift at 7 a.m.

They found the motorcycle. The killer ripped off the plates and chiseled off the VIN. But there was something he missed, something the police almost missed, too.

A constable was dusting the bike for prints when he removed the seat and found the vehicle registration.

“He had unwittingly given us another link in our evidentiary chain,” Leishman writes.

That was enough to get the police to Burnaby where they found Roy Ocol. About one month earlier, Ocol put his motorcycle for sale. A guy showed up, asked to take the bike for a test drive, and, as a sign of good faith, handed him a set of car keys while gesturing to a car parked across the street.

“He rode off, never to be seen again and obviously, the keys he had given were not connected to the car.”

Ocol didn’t get a thing for his bike. But he remembered what the guy looked like.

Being a detective is a bit like being a sushi chef, where knowing what to get rid of is almost as important as knowing what to keep.

One of the most bizarre links in the case involved a heretofore unknown band of revolutionaries dubbed Direct Action. According to their typewritten missive sent to The Province newspaper, Direct Action was devoted to live up to “label of terrorists and urban guerillas” while fighting “against the Capatilists (sic) and their projects.”

It wasn’t necessarily something to keep, but Leishman wasn’t going to throw it away, either.

Leishman had at times a trying relationship with the media but perhaps the biggest break in the case came from a noon hour news broadcast of Persowich’s memorial.

Someone who knew the killer saw the broadcast and was “moved by the pictures of the grief stricken Kay Persowich and her family.”

Now the police had a description, an MO, and a name: Ladysmith resident Evan Clifford Evans.

Police immediately started surveillance.

According to Leishman: Evans was a rarity: a paranoiac who really was being followed. He walked into a dead-end alley to blow the cover of a trailing officer and shook a van with blacked out windows, shouting: “I know you are in there,” as the surveillance officers hugged the floor.

On Friday, July 13, Leishman and McKay arrested Evans.

Evans asked for the date, Leishman recalls.

“It is Friday the 13th, do you feel lucky?” Leishman told him.

Evans didn’t go gently. Police found the stolen cash in his possession. Evans told them he was a drug dealer and got the money from one of is buyers.

“It was his contention that the ‘mystery man’ must have robbed the Brinks guard and passed the money along to him for drugs,” Leishman writes.

It might have held up if not for the testimony of a teenage girl who’d been working at Purdy’s Chocolates on the day of the murder.

“She was taking boxes to the garbage and as she walked past the square wooden bench, outside the liquor store, she noticed the young man with the motorcycle helmet sitting on the bench.”

The girl picked Evans out of a police lineup.

Also helping to seal the case was a typewriter seized from Evans’ Ladysmith home. A close inspection revealed that was the typewriter used for the Direct Action manifesto.

“It seemed fairly obvious that he intended to murder the Brinks guard and had taken extraordinary steps to hide his identity,” Leishman writes.

The detective charged Evans with first degree murder and 28 counts of armed robberies for which he would eventually serve 25 years.

Before the trial, Leishman had to fingerprint Evans again.

“He stepped back into a corner, clenching his fists and said there was no way he was going to let us print him,” he recalls.

Leishman told him they could do it the hard way. He took off his jacket, unloaded his gun and handed it to another officer.

“Evans was mesmerized, not knowing what was going on.”

That was when Leishman sprang at him and got his prints “without incident,” he writes.

B.S. still baffled brains.

After the badge

Leishman has been retired for 22 or 23 years.

“You lose count,” he says cheerfully.

He travels with his wife. He writes. He talks shop with his son who’s been a police officer for about 20 years in Vancouver.

“I’d be lost today,” he says, marvelling at the implications of DNA evidence.

Being a police officer was the right job for him. In the early 1970s he had a job driving a truck for union wages, he says. But he wanted to be a police officer, even if it meant a pay cut (and it did).

“I enjoyed the freedom of being a policeman,” he says. “I think it was a lot freer in those days.”

Much like the officers who were on their way out when he was on his way in, Leishman says he wouldn’t want to do the job now.

“The courts are really tough,” he says. “Paperwork is horrendous.”

He also knows there was a way of doing things back then that might not work anymore.

In his book, he writes about a constable ripping wires out of a car to silence a honking driver’s horn.

“Some people would say, ‘That was abuse of authority’” he says. “Perhaps it was. But it worked.”