As a defenceman delivering big hits in the Western Hockey League in his teenage years, Scott Ramsay saw concussions as little more than “getting your bell rung.”

But a string of debilitating head injuries not only ended the promising athlete’s career at the age of 19, his invisible wounds also left Ramsay with severe insomnia, chronic irritability and searing migraines that he tried to manage with a handful of different medications.

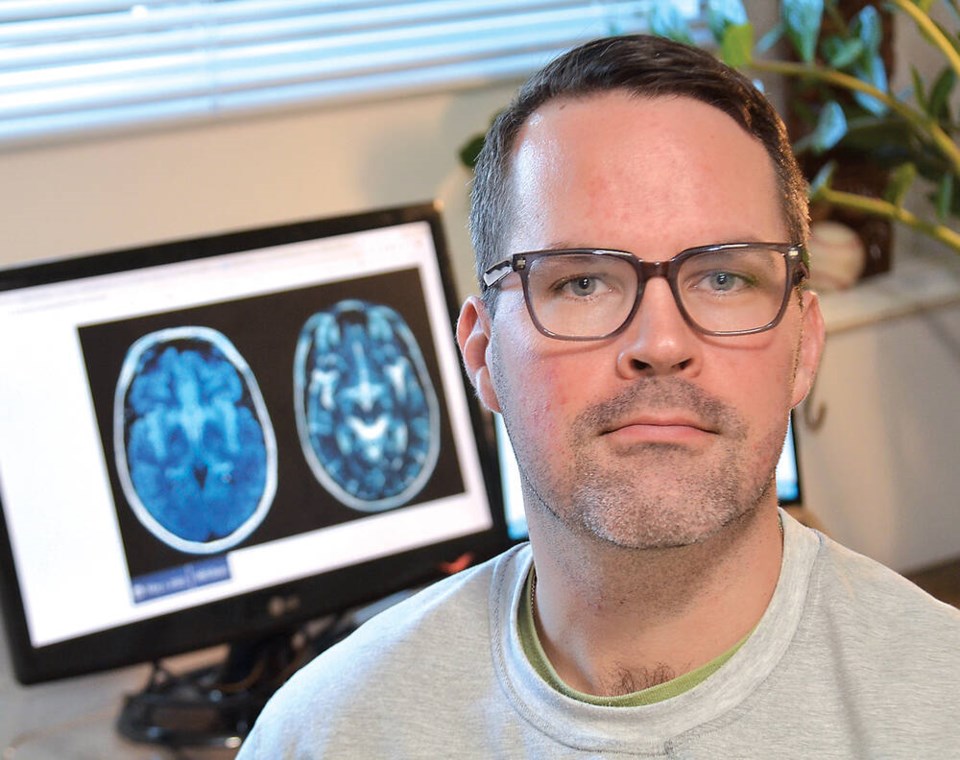

Now the recent PhD graduate is focusing his career on making sure that what happened to him doesn’t happen to other kids. Ramsay’s dissertation – the largest of its kind, with close to 23,000 young people from B.C. identified with concussions – shows a key relationship between timely follow-up visits with doctors and post-concussive symptoms that develop.

As a youth himself, Ramsay didn’t think concussions were anything more than a bump on the head. After a bump like that, you might miss a week or two here or there, he thought. “I didn’t really think that they were anything serious,” he said.

Then, getting three concussions in 13 months would turn his world upside down.

“I would sleep two hours a night. I had migraines, 10-out-of-10 pain. I was on four or five different medications to manage the pain. I was irritable. I was depressed. I was anxious,” Ramsay said.

He also experienced photophobia, which is a strong sensitivity to light. “I had to sit in my parents’ living room with sunglasses on during the day,” he said. “I was basically a skeleton of myself.”

Ramsay’s condition also put a strain on people around him. “My mom said if she didn’t know that I was her own son, she would have kicked me out of her house – that’s how bad of a human being I was,” he said.

With his hockey career at an abrupt end, and high school wrapped up, Ramsay found himself in an isolated haze, able to do little else than keep his job working at a hardware store.

But when it came to his recovery, Ramsay put the work in. After years of retraining his body and mind, he’s gotten to a place where daily life is much more manageable. He’ll still get little bouts of vertigo, and migraines every once in a while, “but the difference between then and now is that I recognize it and I have skills to offset when I know something’s happening.”

All of these experiences have led Ramsay to pursue a career as registered nurse, and to carry out research in the area of youth concussion care.

“I started out by wanting to do this to help one kid, and prevent what happened to me to happen to them,” he said.

Ramsay’s recent PhD dissertation at the University of British Columbia emerged from his clinical practice in outpatient neurology at BC Children’s Hospital.

“We kept getting these kids 6, 7, 8 months post concussion, and they were having these super debilitating symptoms, similar to what I went through with my post-concussion experience,” Ramsay explained.

That drove him to investigate what literature there is for post-concussion follow-up visits, and what resources are available in B.C. “There’s not a lot, depending on the age group, where you live, and if you don’t play sports,” he said.

By examining thousands of young people affected by concussions across the province, Ramsay was able to show that young people who had a delayed follow-up visit with a doctor were significantly more likely to develop post-concussive symptoms than those who had a more timely follow-up.

Ramsay found that more than three-quarters of patients had no follow-up at all. That’s around 20,000 young people per year in B.C. who aren’t getting proper care, he said.

By spreading the word through interviews, and educating health care professionals, Ramsay hopes his research will help improve care for people suffering from concussions.

“If people aren’t getting care out in the community, then I think we have an obligation as health-care providers to provide that appropriate level of care,” he said.

But making changes at the policy level will take time. “In terms of mandating a timely follow-up visit, it’s going to be, I don’t want to say a whole career’s work, but it’s going to be a lot of work over the next decade.”

Ramsay recognized for mentoring fellow Indigenous students

As a finalist for the University of British Columbia faculty of applied science’s Rising Star award, Ramsay was lauded for his work mentoring new Indigenous graduate students.

Ramsay, who is Métis, said he sees mentorship as a way of giving back.

“As someone who is Indigenous … I wouldn’t be in the position I am today without the mentorship that I was provided,” he said.

Ramsay also highlights ongoing inequities in the education system.

“There’s a major issue with retention and recruitment of Indigenous nursing students. And often what we find is a lot of those students end up failing or leaving nursing programs,” he said. “And we could have done something very simple to prevent it, by helping them through a class or providing debriefing on the class because there were racial undertones brought up.”

A more representative nursing population will likely lead to better health outcomes, Ramsay said.

“Maybe people will want an Indigenous nurse in their community, because there’s a large Indigenous population or [they’re] on a reserve,” he said. “So if we can break down these barriers, people could feel more comfortable accessing health care.”