When Vancouver architect Michael Green looks up, he sees a world full of wooden skyscrapers.

What’s in a name? If you’re architect and environmental advocate Michael Green, your name is, somewhat serendipitously, your personal and professional credo.

“Design isn’t about being pretty, it’s about meaning—and every project has the ability to tell a bigger story,” Green says, settling into a leather boardroom chair at his Gastown office.

Indeed, Green’s advocacy for wood construction, in particularly wooden highrises, is what has catapulted him from well-respected Vancouver sustainable designer into international “starchitect.”

A Cornell University architecture grad raised in the Ottawa area, it was a stint with internationally acclaimed architect César Pelli in New Haven, Connecticut, that started his career. In 1998, Michael moved to Vancouver where he established a firm with two partners, but it wasn’t until 2012, that he struck out on his own with Michael Green Architecture (MGA) and wrote the book that would help define his career: The Case for Tall Wood Buildings.

The book created such buzz that in 2013 TED Talks founder Chris Anderson invited Michael to discuss his passion: building wood-framed skyscrapers that would help slash construction-related carbon-emissions worldwide. Just over three years and millions of YouTube views later (the talk was translated into 30 languages), Green’s futuristic vision is that much closer to becoming reality.

The tallest modern wooden structure in the U.S. was designed by Michael Green, is located in Minneapolis and was built using trees killed by pine beetles.

Soon, the world’s tallest wood-framed building, the University of British Columbia’s 18-storey Brock Commons, will be erected right here in Vancouver. Michael’s second book, Tall Wood Buildings: Design, Construction and Performance, co-written with sustainable architect Jim Taggart, will be released this spring. And his firm, Michael Green Architecture, is currently conceptualizing four buildings of varying heights in and around Paris, a boom which Green credits to the French capital’s heightened awareness of urban environmental challenges in the wake of hosting the 2015 United Nations Climate Change Conference.

Still, Michael knows there is a lot of work to do when it comes to upsetting “an entrenched global system of skillsets” in the building trades. He is well aware that overthrowing 150 years of innovation in steel and concrete highrises in favour of wood is going to require truly global change. So, in order to advance his sustainable architectural agenda, Green has focused on constructing wood-frame buildings that embodied yet another central pillar of his architectural philosophy.

For Green, the term “social connectivity” isn’t just some feel-good, abstract concept; it’s as integral to a project’s viability as the wooden framework itself. A development must incorporate spaces that focus on human communication instead of commerce: Human sustainability.

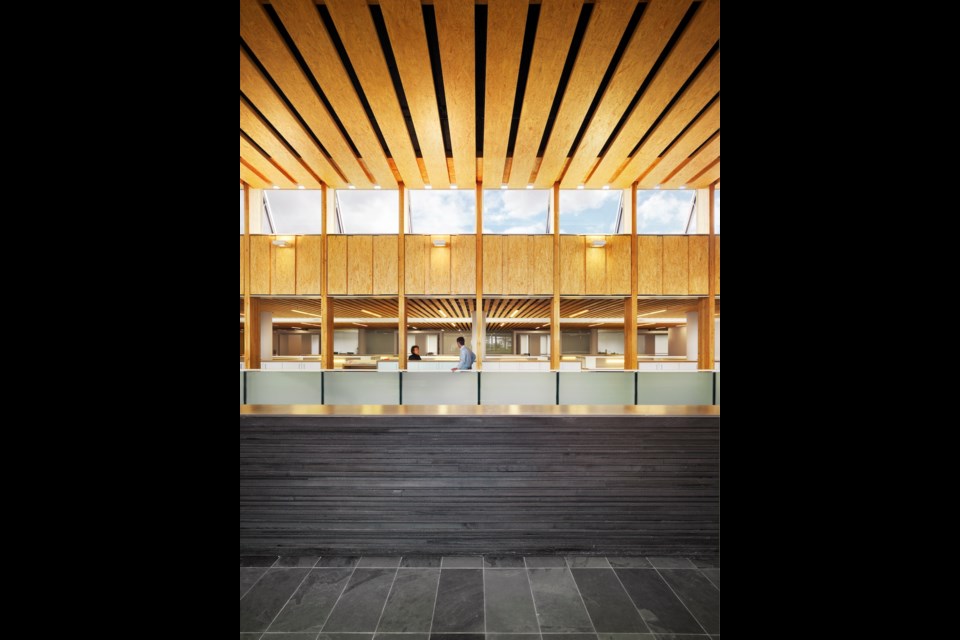

“The idea that our public spaces have to be selling something bothers me,” he says, indicating the trend for gathering spaces to be branded, or feature some sort of retail component. “So, when North Vancouver City Hall gave me my first kick at the can to demonstrate a large, public space free of corporate interests and incorporate advanced wood construction, we ran with it.”

The award-winning building, constructed directly on top of the existing foundation to reduce waste, allowed Green to demonstrate a sustainable, mass timber build; fine-tune advanced, pre-fabricated wood techniques that included zero-waste panels; and bring to reality his burgeoning social agenda. The building’s massive atrium, enclosed by Green’s visionary zero-waste, pre-panelized and engineered roof structure is an indoor agora, conceived, and ultimately utilized for community engagement in the form of public concerts, co-operative dinners and townhall meetings.

One of his next commissions, Ronald McDonald House BC & Yukon, allowed Green to further refine his literal vision of community building. A refuge for out-of-town families with sick children undergoing treatment in the region’s only pediatric hospital, the building had to be functional as well as nurturing, institutional as well as personal, and conceived with a degree of empathy unlike any building he’d designed before. The result was another award-winning, LEED-certified environmentally conscious building made of engineered timber that features two blocks of apartments connected by a central, open common space. Guests can come together for a meal or to interact in that focal great room, but they can also retire to private quarters if they need to.

“It’s the building I’m most proud of,” he says earnestly. “Not only is it built with purpose, but it will have a net-positive carbon footprint, is seismically solid and sustainable and is built to stand for centuries, which doesn’t always happen in Vancouver,” he adds with a hint of a wry smile.

Ronald McDonald House BC & Yukon

If the West Side’s Ronald McDonald House is Green’s dream made reality, then his next venture will project that reality onto the planet. Before the end of the year, Green will harness the power of the platform that brought his message to the masses, launching Timber Online Education (TOE), a free series of architecture, engineering, design, urban development, civics and environmental science courses that bring the wood-frame gospel to anyone in the world with an internet connection.

“We’re going to engage with everyone from global governments to fabricators to the forestry industry to people in construction, right down to the ones who determine the building codes,” he says of TOE. The ultimate goal, he says, is to make sustainability affordable and accessible for everyone, everywhere.