Oil and guns seemed to go together.

It’s early in Lynn Valley entrepreneur Nigel Bennett’s book Take That Leap when he jostles for space in a helicopter alongside two Egyptian oil executives escorted by a bodyguard with a machine gun.

It was the mid-1980s and Shell, Amoco, and BP were flocking to the Gulf of Suez to get a 49 per cent share of Egypt’s black gold. Egypt would control the other 51 per cent but no one controlled the oil itself, which lapped up in bubbling black waves on filthy beaches. Armed with a camera and some mapping equipment, Bennett writes about looking down from the chopper to see an ebony lake in the desert, the result of a pipe rupture that hadn’t been fixed in three months. He remembers stepping off the highway to relieve himself and realizing he’d stepped into

a minefield.

“We are so far from no place,” his helicopter pilot tells him.

The pilot, a Vietnam vet and a swearing southern gentlemen, tells Bennett about the constant ooze in the gulf. “You think the suits in Cairo, Alexandria or Houston care?” he asks. “Nobody sees this hellhole.”

Working for his father, Bennett’s job since the age of 18 had been to map those hellholes on translucent sheets of acetate. It was a career that’d come his way scant hours after graduating from West Vancouver’s Hillside Secondary. He’d done the customary celebrating of a high school grad and returned home in the night’s wee smalls to find a plane ticket waiting on his pillow. The flight was bound for Caracas, Venezuela. Departure time was tomorrow.

There had been no conversations with his father about what he would do after high school, Bennett laughs. There was just the ticket and an unstated invitation to adventure.

But he’d barely arrived when he thought he was about to die.

He was hanging out of a chopper over a pipeline in south Venezuela when he a voice yelled in Spanish: “Move away from this area or we will shoot you down.”

Bennett’s understanding of Spanish was rudimentary but he didn’t need a translator.

The Revolutionary Armed Forced of Colombia were gaining a reputation for kidnappings and blowing up oil pipelines to protest the nation’s rampant inequality.

There were flashes of light that could’ve been guns and then the helicopter took off.

Despite the fear, or maybe because of it, Bennett agreed to go to a party that night. There was music and dancing and corn and pork and rum; lots of rum.

He got sick.

A wasted morning turned into days of sickness as Bennett tumbled in and out of consciousness.

He was eventually diagnosed with a parasitic infection that would, he writes, “seemingly come alive again and again.”

“I think it was the best thing that ever happened to me,” Bennett says of the trip.

The parasite is just what he ended up with. What he was given, he explains, was “the gift of travel.”

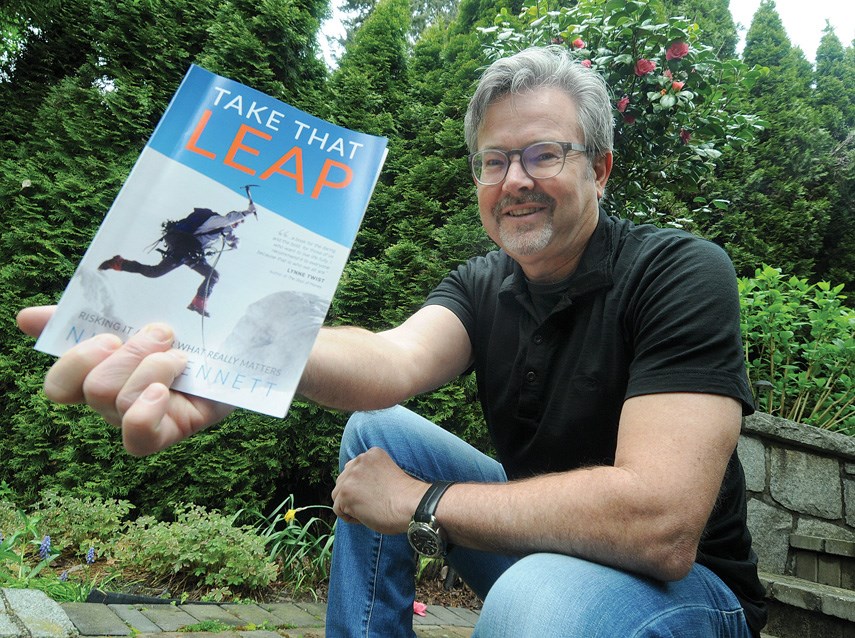

Take That Leap brims with optimism, focusing on Bennett’s eventual decision to break away from his father’s company and found Aqua Guard Spill Response, which manufactures booms and skimmers and other barriers designed to sop up spilled oil.

That decision to found his own company was largely influenced by the Exxon Valdez spill in 1989, he writes.

While Bennett had seen “the spaghetti of 25-year-old pipelines” leaking oil, it wasn’t until millions of crude blackened the coast of Alaska that the conversation changed, he says. Before then, oil spills happened “behind closed doors in remote regions of the world.”

The Exxon Valdez was: “right in North America’s backyard, and people everywhere were angry.”

Bennett didn’t want to live his life in crisis mode the way his father did, he writes.

“. . . everyone has skeletons in their closet. My skeleton, as I was starting to understand, just happened to be my father.”

Bennett devotes several sections of his book to the oil industry’s “total disregard” for the environment. He notes that some companies leave their corporate logo off their tanks farms and oil terminals to sidestep public outrage in the event of a spill.

But Bennett retains his optimism when it comes to business itself, which he describes as “the best framework” for alleviating environmental catastrophe.

But to understand Bennett’s optimism about business, it’s necessary to understand his idea of what a business should be.

Around 2010, a “very large British company” approached Bennett to buy his company.

“I thought: ‘Oh my gosh this is it, this is every entrepreneur’s dream,’” he recalls.

But while the papers were being prepared and the cigars were being rolled, Bennett had an epiphany. He was in the Amazon, thinking about money. Yes, he could sell the company. Yes he could sell the company for a lot of money.

But what, he wondered, what would he do with his life?

He yanked the deal off the table, somewhat to the consternation of a partner who was ready to cash out.

“We’re going to keep the company, we’re going to leverage the heck out of it to do good in the world, whatever good is,” he remembers saying. “That’s the benefit of a private company over a public company.”

Aqua Guard has done business in 104 countries, Bennett says. He attributes the company’s longevity to his willingness to leave the helm from time to time.

“We just think, ‘We can’t leave, we can’t leave our business because everything’s going to fall apart.’ It’s actually a bit of a myth,” he says. “There’s always a business crisis. Everybody’s got crisis every day.”

But when you carve out some time, either to climb a mountain or go to your kid’s soccer game, you tend to return with a clear mind, Bennett explains.

It also helps you achieve a balance.

“You start chasing the shiny objects everywhere,” he says. “If you lose your family along the way, it’s really not worth it.”

He’s known many entrepreneurs who have flourished at the expense of their families.

“Some of them turn 50 and they don’t know their kids,” he says.

To remedy that, Bennett says he gave his three children the gift of travel as well, bringing them with him and his wife just about everywhere they went.

With young, talented people running his company for him, Bennett has been able to devote more time to charity and to his family, he says.

What truly changed him was building a home in Mexico about 15 years ago, he says.

He remembers working alongside the Mexican family whose home was a tarp slung over two garage doors atop a “wet, grimy mattress.”

With his hands blistering and his young children co-operating at an unprecedented level, Bennett felt a metamorphosis.

“When I saw my daughter all covered in paint, standing in the dirt, building a house for a homeless family that had been living in the dirt, working beside a little three-year-old boy all covered in paint, both of them laughing and basically painting each other, that was it, that did it for me,” he says.

It’s in the teachings of Buddha and “probably in the bible,” he says, that “there’s nothing more powerful” than giving.

But through all his travels and travails, there is nothing, Bennett says, more powerful than giving as a family.