A stroke is a thief.

For a few minutes or for a few days the blood stops flowing to part of the brain. The machinery of the body breaks down and the stroke starts taking.

“It takes away your confidence, it takes away your balance, it takes away your feeling that there’s nothing you can’t do,” explains West Vancouver artist Jane Clark.

From behind a steaming cup at a Lower Lonsdale coffee shop, Clark, always the landscape painter, takes in the scene outside the window.

“Before I could’ve probably put on a pair of roller skates and roller skated down here,” she says. “Now I couldn’t dream of doing that.”

Clark, 90, suffered a stroke in May. It lasted for three days.

“If you say that, it sounds terrifying,” she says with a chuckle.

She lost mobility in her left arm and left leg. She couldn’t talk.

“Mercifully, my brain wasn’t damaged and if it was, it was minor,” she says.

Clark recalls being in a hospital bed and thinking about when she might be able to talk again. She convalesced in the hospital for seven weeks. When she got out, she worked through seven weeks of intense rehab. After that, she began moderately intense rehab.

“I wasn’t a very good patient in there because I have no patience,” she says with a smile.

She speaks clearly and with great wit and endurance. But her voice is a bit thick, she reports. She also has saliva and swallowing problems.

“I’m trying to get the leg back but the arm won’t come back,” she notes.

But the major thing was to get back to painting, she says.

Clark still can’t hold and open a tube of paint by herself, she says.

“I couldn’t do anything at the beginning,” she says. “But I’m back to painting.”

She has to depend on others now. And perhaps just as challenging, she has to accept that she needs to depend on others.

“As an artist I have to adapt to not being able to drive myself, not being able to go out where I want to and relying on other people. This is a world that I’m not used to,” she says.

But she’s back behind the canvas. She had to alter almost everything she does to work around the effects of the stroke, but she is working.

“I’ve adapted everything I’ve got to try to get back to work because that helps my brain,” she says. “The landscape painting is my way of putting myself back on my feet.”

It’s not exactly a metaphor. Clark is confined to a wheelchair but she’s hoping her work will help her get healthy enough for a northern trek she’s been looking forward to for years.

Next May, just one year after her stroke, Clark is planning to head to what she calls the “raw country,” at the end of British Columbia, just south of Yukon territory.

“All I have to do is get there,” she says.

Sipping her drink, Clark leans forward and talks about her hope to find a helicopter pilot who’s “brave enough to go,” and: “crazy enough to go low.”

With that kind of helicopter pilot you can get a dazzling look at the Grand Canyon of the Stikine.

Clark ventured there in the 1990s and recalls seeing wild goats clambering across rocks while perched over a 300-metre drop.

“From the artist’s point of view it’s just . . . magical and wild,” she says.

She’s not ready for a trip like that yet, but she will be, she promises.

“I have to know if I can do it,” she says. “I can’t just go and not function.”

The difficulty is staying energetic for a long period, she says.

“Before it was never an issue. Now I think after about 10 hours I probably would be beat,” she says, adding: “I am 90, I’m supposed to be beat anyway.”

Her eyes widen slightly as she talks about painting glaciers.

It’s a demanding, exacting skill, she says.

As the helicopter flies over jagged skyscrapers built of ice the artist has a few seconds to rapidly sketch what Clark calls: “lines that mean something.”

The colour and bits of texture can come later, but those first few lines are essential to capture the size and shape of the glacier.

“There’s no time to dither and wonder whether you can do it or not do it, you have to be able to do it,” she says.

Clark has become a master at it, she says.

“Twice over an area and I’ve got it.”

The hunting lodge where she’ll stay is booked. The arrangements are made. She just has to be well enough.

“I have a world that ticks if I can just get back to it,” she says.

Up there, the land is a place that Canada hasn’t really looked at, Clark says, before adding: “Thank goodness.”

The land is likely rich with natural resources, she says.

“The ground is money. If we’re stupid enough to get it, then we will ruin the world up there.”

Money, Clark says, is a “false way” to build a world.

“Buildings go up, come down, get rid of them,” she says. “More money. Money in different pockets. It doesn’t do anything. It’s not doing anything creative it’s not helping the world.”

The demolition of buildings is a personal issue for Clark.

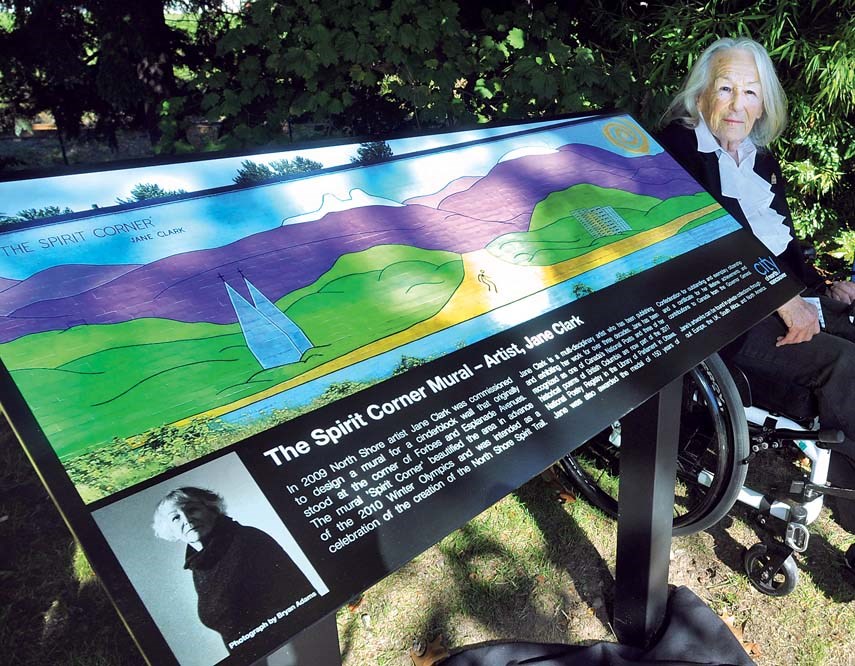

In 2009, Clark won a competition to festoon the 2,000-square-foot cinderblock wall at Esplanade and Forbes Avenue with Spirit Corner, a mural celebrating the upcoming Olympics. The mural was also meant to cover the graffiti that was often scrawled on the Hesp Automotive wall.

But in 2016 Clark discovered the building, along with her mural, were set to be demolished for Alcuin College’s Lower Lonsdale location.

“They have a right to demolish it,” she says. “But they morally should have informed me and come to some agreement with me about that.”

Clark campaigned for her mural to be saved.

“Nowadays we destroy things with only thought of the immediate moment to make a buck. No thought it given to a heritage or the next generations, only the expediency of the moment.”

Recently, the mural – albeit in a much smaller scale – was reproduced on a plaque at Waterfront Park. Clark noted she was “exceedingly “grateful” to City of North Vancouver Mayor Darrell Mussatto for finding a solution.

The conundrum of what should be done with the mural underlined issues of the rights of the artist, the public’s ownership of public art, and the need for preservation, Clark says.

But the situation also got her thinking about graffiti.

While some graffiti, is: “an expression of hatred by somebody who is going through their own personal hell,” other work is brilliant, she says.

“I’d love to have done it,” she says with a grin. “There are loads of places that would benefit from a bit of brightness.”