A glass Pepsi bottle caked with dirt. A rusty bed spring shrouded in fresh greenery. A wooden ski tip poking through the brush.

To the casual Mount Seymour hiker, it might look like litter in the woods, an unfortunate blight on Mother Nature. But mountain resident Alex Douglas sees more than trash. He sees clues that could help him uncover an overgrown piece of North Shore history. To Douglas, these weather-beaten artifacts are evidence of the bustling cabin community that once thrived on Mount Seymour. During its heyday, in the years after the Second World War, he estimates up to 300 rustic log cabins dotted the side of the mountain.

As a matter of course, time and the elements were not kind to these simple structures. Many collapsed under the weight of heavy snow. Others were burnt to the ground by government authorities when they fell into disrepair.

Today, Douglas estimates 15 cabins are still standing. Of those, just a handful are being well cared for by owners who lease the land from B.C. Parks for $550 a year.

As lead historian with the Mount Seymour History Project, Douglas has spent the last 20 years archiving photographs, interviews and documents relating to cabin life. And as an avid hiker, he has also been combing the backcountry for long-forgotten cabin sites — with some success.

Now, he wants to share his findings with others. New this summer season, Douglas is leading Uncle Al’s Cabin Tours, introducing hikers to Mount Seymour as the early pioneers would have known it.

• • •

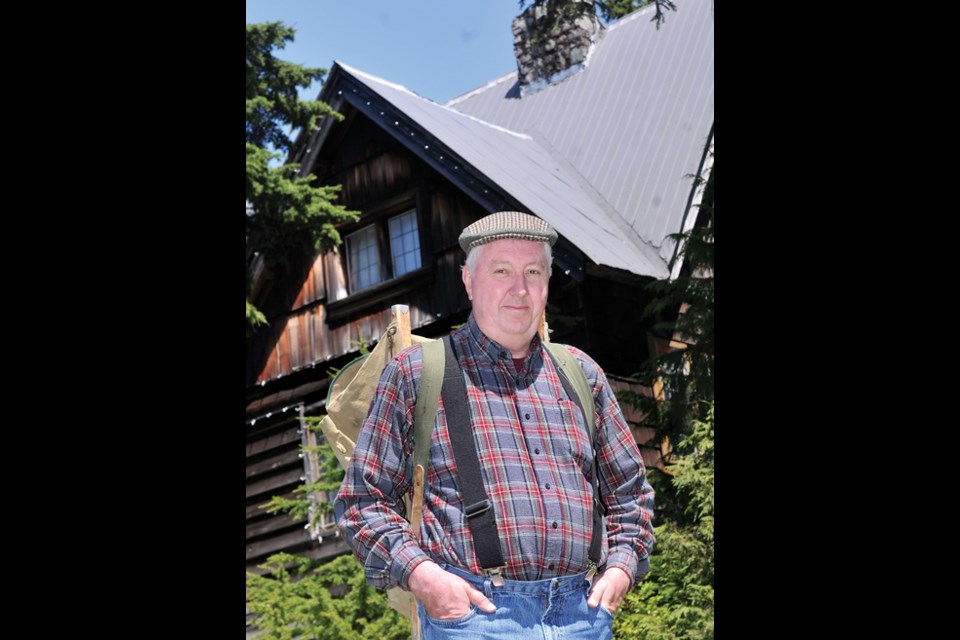

Wearing a plaid shirt, suspenders and with a Trapper Nelson pack strapped tightly to his back, Douglas navigates Seymour’s trail system with an intimate familiarity. Grazing past blueberry bushes and side-stepping muddy patches in the Goldie Lake area, he pauses where a chunk of rusted metal, once part of a bed frame, lies in the lush undergrowth at the side of the path.

“I suspect at one point somebody was carrying it out to get rid of the metal and just gave up and left it there.”

Here, he veers off the marked trail, pushes aside some low-hanging boughs and enters a densely forested area where a more inexperienced hiker could easily get lost.

“This is what I’m looking for when I’m bushwhacking,” Douglas says, pointing to a stretch of tamped down earth. “It kind of looks like a trail.”

After following this barely-there path for a couple of minutes, a manmade structure appears through the evergreens — a two-storey cedar log cabin. Out front are the charred remains of a fire pit and a raised outhouse.

“Welcome to Cabin 147,” Douglas announces proudly.

Little is known about this building, he concedes. It could have been built as early as the late 1930s, around the time Mount Seymour Provincial Park was established. By that point, both Hollyburn and

Grouse were already well-established summer and winter recreation sites.

“A lot of the old pioneers have said that they came to Seymour because those two places were too busy,” Douglas explains, noting it was 1939 when Harold Enquist opened the Seymour Ski Camp.

There was little cabin-building activity during the war years, he says, but things picked up again between 1946 and 1951.

“Once you got to ’51 and the (Mount Seymour) Road was in, you didn’t need the cabins anymore because you could theoretically drive all the way up here.”

Before the modern-day road existed, people would drive up an old logging route, park at the Mushroom Parking Lot (better known today as the Vancouver Picnic Area) and hike two hours to the ski runs.

While the construction date of Cabin 147 remains a mystery, Douglas believes the second storey is a more recent addition.

“You’ll notice it’s got steel on the roof and it’s actually got steel beams. I suspect that it was a one-level cabin and that, at some point in time, once the road was in and they were able to put the steel onto toboggans and just slide it down over the snow, they added another level to it.”

• • •

In high school, according to his yearbook at least, Douglas aspired to become either an electrical engineer or a ski bum.

“So I’ve achieved one of my goals,” he says with a laugh.

Before retreating into the mountains, the Ontario native was headed down a path towards a very different lifestyle. After college, he started an apprenticeship at a steel company in Hamilton.

“After three years, I realized I was going to marry one of the technician’s daughters because they were all inviting me over to their homes for supper and introducing me to them. I was going to have two-and-a-half kids, a station wagon, a mortgage and a dog, and die an old man,” he says. “So I decided to come west and join the ski area.”

A “new import” compared to the pioneers of North Shore mountain recreation, Douglas moved to B.C. in 1975 and immediately started working at Seymour, “and they haven’t been able to fire me yet,” he says.

He’s currently the rentals manager at Mt. Seymour Resorts Ltd. and his workplace, the Alpine Activities Centre, is just a short, scenic walk from his mountain-top house, which is known as Ole’s Cabin.

Formerly the forestry administration building, it was erected in the early ’40s by Swedish-born Ole Johansen, who became Seymour’s first park ranger. Though the cabin has been renovated over the decades, the original logs still form the interior walls.

Douglas has lived in this house year-round for the last 15 years with his wife, whom he first met at a summer ski camp in Whistler.

“I was the first-aid attendant and she was a young camper and knocked herself out,” he says. “As the old story goes, I had to give her the kiss of life.”

The couple celebrates their 25th anniversary this October.

“We literally have won the lottery because of where we live and the lifestyle we’ve managed to eke out,” he says.

• • •

Douglas interrupts his historical narrative now and again to recount the amusing personal anecdotes that come with living in the mountains. There was the time he fell into a brush-covered outhouse hole.

And once, he came face-to-face with a blueberry-eating bear.

Back on the topic of Mount Seymour history, Douglas says the number of cabins plummeted during the 1960s.

“Definitely the attitude of (B.C.) Parks changed in the ’60s and, especially if (a cabin) was in rough shape or if the roof collapsed because of the snow load, then they would burn them down,” Douglas says. “And so that got rid of a lot of cabins. I would say that by the ’80s, we were down to maybe 30 cabins on the mountain.”

The absence of a cabin hasn’t stopped Douglas from seeking out and learning from empty lots. Along Goldie Lake Trail, he again strays from the beaten path and sets out into the backwoods.

“There actually was a trail through here, but, as you can see, the forest has the amazing ability to take it over.”

He grabs hold of a rope that he installed to ascend a steep section and clambers over lichen-covered rocks, passing a flattened can of turpentine and a hand-winch, partially buried in the ground, which was likely used to hoist logs during construction.

“There’s all the beauty of Mother Nature, but every so often you do find remnants of man’s interaction with the forest,” Douglas says.

These particular remnants lead to a plateau with a sweeping northeasterly view. On the ground, fragments of glass and a pile of bricks are all that is left of Cabin 116.

“We’ve come to the conclusion that the cabin, for a few purposes, must have been built right up here. But if it was burnt down in the ’60s, it probably has long since disintegrated.”

Today, leaseholders aren’t allowed to live in their cabins permanently and they aren’t allowed to rent them out for profit. For many, the reality of cabin ownership can quickly quash any romantic ambitions of taking over the lease on an old fixer-upper.

“When people see these things, they get all excited and they want to help and they want to see them preserved,” Douglas says. But, tell them it will cost several hundred dollars a year for the lease and potentially tens of thousands of dollars to replace the rotting wood and ensure structural safety? “Then all of a sudden everybody starts changing their tune.”

• • •

Back at the Alpine Activity Centre, Douglas has assembled a display of old maps, photographs and newspaper clippings documenting the history of the cabin community on Mount Seymour. He has 20 more boxes of “odds and sods” at home, including recorded interviews with pioneers.

During the summer months, when he’s semi-retired, Douglas can spend more time working on the Mount Seymour History Project, tracking down the descendants of former cabin owners, making connections with people who once frequented the ski hills and hiking trails, and gathering information about each and every cabin that ever stood.

“There’s a lot more history to be recorded,” he says. “My ultimate goal is to let people know that there’s more than just the trails, that there are things in the woods if you go a little bit further.”

Uncle Al’s Cabin Tours run now until the end of September. Visit mountseymour.com/guided-hikes or call 604-986-2261 x217 to register for a scheduled three-hour tour ($19 per person) or to book a group. Visit mtseymourhistory.ca for more information about the Mount Seymour History Project.