The mining industry would see a financial windfall from a global carbon tax, so why does it keep fighting change? That’s the contradiction researchers from the University of British Columbia examined in a study that has provoked strong opposition from the oil and gas industry.

The research, published in the journal Nature Communications Earth and Environment last week, provides evidence that, under a global carbon tax regime, mining companies would gain a competitive advantage over a variety of commodities across the fossil fuel industry, agriculture and construction.

At the best of times, the mining industry has remained fractured in its support of carbon tax schemes. Some companies have backed prices on carbon, while many industry organizations, like Minerals Council of Australia, have slammed carbon taxes as anti-job.

As a Mining Association of British Columbia advocacy paper echoed in October 2020, the carbon tax is “the single greatest barrier to the competitiveness of B.C. mining.”

It’s a message the study’s lead author Benjamin Cox says he’s heard a lot.

“The mining industry as a whole has this jerk reaction to carbon tax much like a meat-eater has a knee-jerk reaction going to a vegan restaurant,” said Cox, a PhD student at UBC’s Norman B. Keevil Institute of Mining Engineering.

“‘How dare you say we go there? We don't have anything to do with that. Those aren’t our people.’ And what we're trying to say is, ‘Yes, the environmental movement, the pro-carbon-tax movement are your people. Get behind them. Support them.’”

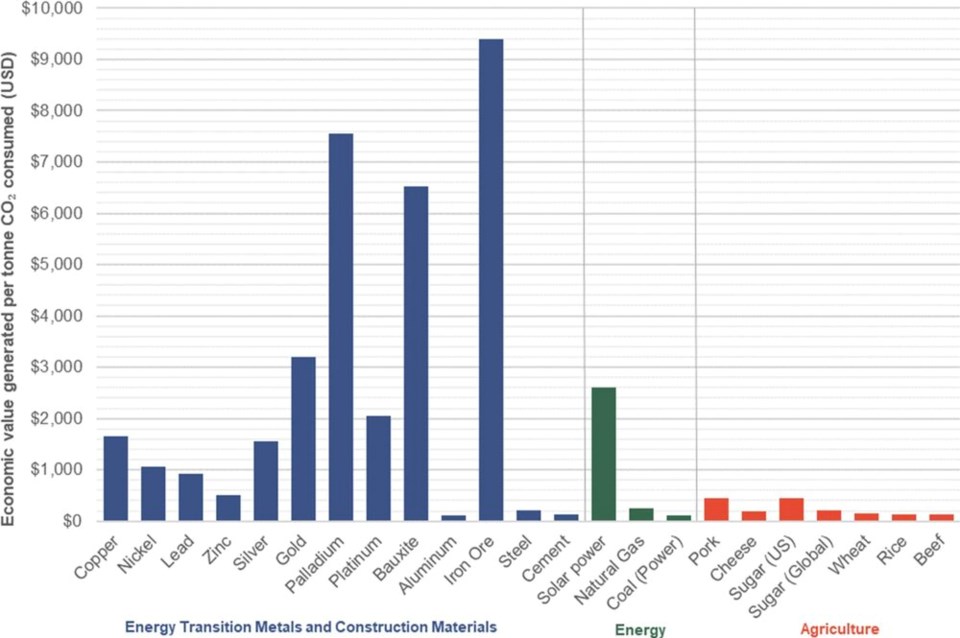

Cross-referencing public data on the carbon footprints and dollar value of 23 commodities — from aluminum and copper to pork and cheese and coal and oil — Cox and three other researchers have put a wrench in the narrative that all taxes are bad for business.

To make that transition to a low-carbon future, the mining of minerals like lithium, cobalt and rare earth metals are expected to skyrocket: the World Bank estimates more than three billion tonnes of minerals and metals will be required to deploy enough wind, solar and other green technology to maintain global heating below the Paris Accord target of 2 C.

Today, the global mining and metals industry makes up eight per cent of humanity’s carbon footprint. But when comparing it to the fossil fuel or agricultural industry, the researchers found mining generated significantly more value for every tonne of emissions released into the atmosphere.

For every tonne of C02 produced in the mining of iron ore, for example, the industry generates US$9,400. Those same emissions yield only about $250 worth of natural gas or $200 worth of cheese.

Perhaps most surprising, said Cox, the extraction and processing of metals like palladium and bauxite produce more than double the value the solar panel industry produces for every tonne of emissions.

HOW WOULD A GLOBAL CARBON TAX HELP?

To date, more than 40 countries and over 30 sub-national jurisdictions have adopted some kind of carbon pricing. (The Canadian government is planning to raise the federal carbon tax to $50 per tonne in 2022 and up to $170 per tonne by 2030.)

But that leaves over 150 nations without some form of carbon pricing — a key financial mechanism experts say is working to drive economy-wide change.

Enter a global carbon tax. If it were set at $150 per tonne of carbon dioxide, the study found the cost would raise mining industry commodities between two and 30 per cent of their current value. By comparison, a similar global carbon tax would raise the cost of natural gas by 60 per cent, cement by 109 per cent, beef by 120 per cent and coal by 145 per cent.

Today, Cox says consumers end up choosing fossil fuel products or beef over their less carbon-intensive counterparts — essentially because they are cheaper. But take carbon into account, and the balance would almost certainly tip in favour of products laced with commodities like copper, a key component in everything from wind turbines to electricity cables.

“From a GDP perspective, the mining industry has nothing to fear from carbon taxes because it will just pay less tax on a relative basis,” said Cox.

There are some exceptions.

The manufacturing of steel requires both iron and coking coal — the latter something the industry has yet to find a good substitution for at scale. So while a global carbon tax wouldn’t directly impact iron mining operations, steel manufacturers and companies mining coking coal would be harder hit, and therefore will likely put up a bigger fight against a carbon tax, notes the study.

Producing aluminum, on the other hand, requires vast quantities of bauxite and energy. Its steep energy demands and lower value give the metal a relatively high carbon footprint.

But even here Cox points to several Canadian operations, such as the Rio Tinto aluminium smelter in Kitimat, B.C., that mostly rely on hydroelectricity.

Relying on hydro power means that while Canada’s nine aluminum plants make it the fifth-largest producer in the world, the industry also operates with the lowest carbon footprint — roughly a third of other manufacturers, notes the study.

There are some signs industry leadership is taking climate change more seriously. According to PwC’s 2021 CEO Survey, 76 per cent of global mining and metals executives said they were concerned about climate change and environmental damage. That’s up from 57 per cent a year earlier.

Brendan Marshall of the Mining Association of Canada (MAC) says the organization supports the federal government’s current approach to pricing carbon, as well as improving the system over time.

“If you had a global carbon price and you had a level playing field with carbon as the restricting factor, Canada would have a competitive advantage,” agrees Marshall, MAC’s vice-president of economic and northern affairs and its climate policy lead.

“Large segments of our mining community would stand to benefit from a global price on carbon.”

But Marshall says it's not just climate hanging over the mining industry's head. There are also huge concerns over national security as global fault lines emerge between the U.S. and its allies, and China, where much of the battery-grade minerals and rare earth processing is located.

“There is a race on to capture segments of these supply chains. And China is ahead,” said Marshall.

Many companies and governments are looking at the current microchip supply chain crunch in the automotive industry as a warning. They don’t want to be exposed in the same way over batteries, said Marshall.

Canada, Marshall says, is well-positioned to step in as an alternative: the country has the “sustainability bonafides,” a fairly healthy trade relationship with the United States and an abundance of the minerals big manufacturers want.

“The climate-driver is apparent, but there’s also a national security aspect,” he said.

CARBON TAX WON'T FIX MINING'S OTHER PROBLEMS

Three-quarters of the world’s mining companies are based in Canada, with many of those operating in other countries. No global carbon tax will solve the Canadian mining industry’s mixed and often tarnished record of riding roughshod over communities and political systems.

Despite a long record of human and environmental abuse — including evicting villages, contaminating water sources and being implicated in several cases of murder — the Canadian Ombudsperson for Responsible Enterprise has no authority to independently investigate allegations involving Canadian companies overseas, Human Rights Watch said last year.

In January 2021, a groundbreaking Supreme Court decision ruled three Eritreans, who claimed they were forced to work in a mine partly owned by a Canadian company, could have their case heard in a Canadian court.

Human Rights Watch, which investigated the case, said the “landmark decision could open the door for victims of corporate abuses overseas to sue companies in Canada for violations of international human rights law.”

Improving industry oversight could have huge implications at home too.

Domestically, the Canadian mining industry remains massive, employing up to 719,000 people and accounting for nearly a fifth of Canada’s domestic exports. As exploration expands, questions over environmental regulations remain.

Nearly seven years after a four-square-kilometre pond burst its dam, spilling toxic tailings downstream, an internal audit into the Mount Polley mine disaster found changes the government promised to make to its regulatory framework were full of inconsistencies, errors and omissions.

However the regulatory landscape evolves, pressures to mine highly sought after metals will only grow. And with one of the highest concentrations of resources per capita in the world, Cox says that puts Canadian miners in one of the best positions to usher in an era of decarbonization.

“We've had lots of nasty responses in oil and gas people. They don't particularly like it,” said Cox. “When transition happens, the [mining] old guard will throw names at me [too].”

“The fact is, the only way we get to a functional climate change situation is by supporting positions where we have common ground.”