The Vancouver Canucks are known for their Swedish stars, but the first European player in their history was nearly a Finn.

Before Börje Salming blazed a trail with the Toronto Maple Leafs as one of the first true European stars in the NHL, the Canucks came close to signing a European star of their own: the top player in Finland, Lasse Oksanen.

“We’ll go to Sweden, Finland, even Russia — but we’ll get players”

When the Canucks first joined the NHL in 1970, then-owner Tom Scallen was dismayed when they missed out on future Hall-of-Famer Gilbert Perreault to the spin of a carnival prize wheel. He declared that his team would leave no stone unturned in their search for players.

“I’m sad and I’m mad,” said Scallen. “We received a setback here today but it makes us more determined than ever to go out and find our own talent. We’ll go to Sweden, Finland, even Russia — but we’ll get players.”

In truth, it took until 1978 for the Canucks to add their first player from outside of North America when they brought in four Swedes at once — Thomas Gradin, Lars Lindgren, Lars Zetterström, and Roland Eriksson — but it was not for lack of trying. In fact, at their very first training camp in Calgary, the Canucks had two players from Finland listed among the 58 players on the camp roster: Jorma Peltonen and Lasse Oksanen, who were linemates for Ilves back in the top Finnish league at the time, the Finnish Championship Series.

Peltonen never showed. He notified the Canucks that he was going to stay home in Finland to look after his pregnant wife. Fair enough.

The Canucks also tried to bring Swedish defenceman Kjell-Rune Milton to camp; he decided to stay in Sweden, with general manager Bud Poile telling The Province’s Clancy Loranger, “Our offer wasn’t high enough.”

Both Milton and Peltonen stayed in Europe for their entire careers and never took another shot at the NHL, from what I can tell.

Oksanen, however, not only showed up at training camp in 1970 but also turned heads during the preseason, earning a contract offer from Poile.

“You had to do more than just play to make a living”

Poile’s contract offer was significant because Oksanen would have become the first Finnish-born-and-raised player in the NHL. While Finnish-born players played in the NHL before the Canucks joined the league, they were all Finns who had immigrated to North America as kids, like Albert Pudas and Pentti Lund.

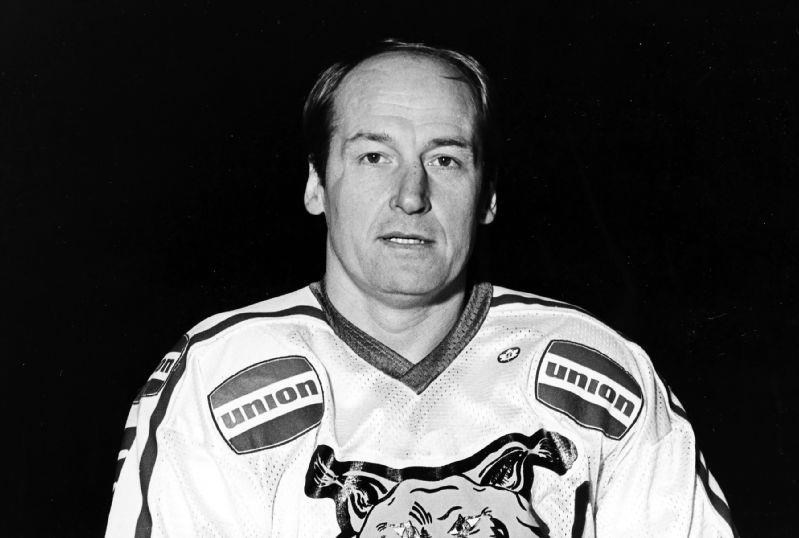

Oksanen, on the other hand, was already a legend in Finland by the time he tried out for the Canucks. He was 27, about to turn 28 later that year, and had already represented Finland at two Olympics and four World Championships. He led Finland in scoring in the 1968 Olympics, putting up 5 goals and 8 points in 8 games.

In the 1969-70 season, Oksanen led the Finnish Championship Series with 32 goals in 22 games, and his 51 points were good for second behind only his Ilves teammate, Peltonen.

In other words, Oksanen had already established himself as a top-tier hockey player, albeit in an amateur league that allowed him to maintain eligibility to play in the Olympics. That meant Oksanen didn’t make a living playing hockey. Instead, he owned and operated a gas station in Tampere next door to the Hakametsä rink, where Ilves played their home games.

“My friends knew me and came up to me and asked what I was doing,” said Oksanen a few years ago to Aamulehti, recalling a time when a few of his Soviet rivals on the ice saw him at the gas station. “I said this was my job. They didn't really understand. They were full-time professionals. We in Finland were semi-professionals. You had to do more than just play to make a living. That's why Finland didn't really do well compared to its eastern neighbor at the time.”

It’s understandable, then, that Oksanen might take the bold step of heading to North America to try his hand at playing professionally. He and Peltonen hired a Toronto lawyer to represent them and made the connection with the expansion Canucks.

“He has a few of the best moves I’ve seen in Canada”

When Peltonen backed out of the trip to Calgary, it was tough for Oksanen, whose skills with the English language were limited.

“The 170-pound Finnish import arrived here knowing just one word of English,” noted The Province’s Tom Watt. “The word is ‘food.’”

Hockey Hall of Famer Babe Pratt, who was working for the Canucks in an advisory and public relations capacity, stepped in to try to help Oksanen out. No one on or around the team could speak Finnish, so he put out the call to all of Calgary.

“Well, first I called every steam-bath in town. Lots of masseuses, but no luck. I mean with the Finnish,” said Pratt. “Then I went on radio and made an appeal. Today, the area round the team hotel was like Little Helsinki. The kid’s got so many dinner invitations he’s taking along his friends to help.”

While Oksanen’s skills with language were limited, his skill with the puck was not. He dazzled both the sportswriters in the stands and head coach Hal Laycoe in training camp.

“Chances are that Lasse is not likely to be going home this year,” said Watt. “[He] impressed everyone with his general good play and then scored what Hal Laycoe described as the best goal of the camp. Oksanen took the puck in full flight, walked around a defenceman and whipped a blistering wrist shot into the top lefthand corner. It was a professional’s goal all the way.”

“I don’t think either of our goaltenders, George Gardner or Dunc Wilson, have seen many better moves than the ones Oksanen put on them today,” said Laycoe.

Oksanen continued to impress during the preseason, playing on the top line with Orland Kurtenbach and Wayne Maki.

“He’s an excellent hockey player,” said Laycoe. “He has a real bag of tricks. He has a few of the best moves I’ve seen in Canada.”

There was just one problem: Oksanen’s gas station.

“He was too bleepin’ expensive”

Oksanen made it very clear to the Canucks that he would only sign a contract if they could ensure he would be playing in the NHL. He understandably wanted assurances that he wouldn’t get sent down to the AHL to play for the Rochester Americans.

It was a hockey decision and a financial decision. Oksanen wanted to ply his trade in the best league in the world. He wasn’t a young prospect trying to prove himself; he was a 27-year-old man with heaps of international experience.

Financially speaking, the Canucks needed to make it worth his while to uproot his life from Finland. That meant a one-way contract, rather than a two-way contract that would pay him significantly less if he got sent down to the minors.

Poile and the Canucks weren’t willing to do that. They offered Oksanen a two-way contract and wouldn’t budge from that offer.

“Oksanen says he’ll go home if he doesn’t stick with the NHL team, but Poile says Oksanen should be prepared to sign a two-way contract — major league and minor — like everybody else,” said The Province’s Clancy Loranger. “He’s high on Oksanen’s ability, but…”

“We’d like him to prove himself in a lesser league,” said Laycoe, “just as we would with almost any boy in his position…There isn’t a guy out there who can come to us and say I’ll play for you, but only in Vancouver.”

It wasn’t just that he wanted a one-way contract, with assurances that he’d play in the NHL, but that he wanted to be paid enough to make it worth his while to leave Finland.

“The Canucks had practically already used up their budget for that season,” said Oksanen. “They offered me a contract that was less than what I was earning in Finland working at a gas station and playing.”

When later asked why the Canucks didn’t sign Oksanen, Poile replied, “He was too bleepin’ expensive,” according to the Vancouver Sun’s Archie McDonald.

It was reported years later that Oksanen’s asking price was $50,000 per season. The Sun’s Jim Kearney reported that Oksanen “told Bud Poile he needed that sum because he would have to pay someone to look after his stations while he wintered in Canada.”

In fairness, $50,000 was a lot in 1970. The Canucks had just cringed at signing their first-round draft pick, Dale Tallon, to a $60,000 per year contract, which was a rookie record at the time.

That soon changed. By the end of the decade, $50,000 per year was the lowest a Canuck was being paid.

“The first in what grew to be a long list of mistakes”

Oksanen returned to Finland and continued to star for Ilves and the Finnish national team. His last World Championship with Finland was in 1977, where he still finished third on the team in scoring with 9 points in 10 games.

He finished his international career with 282 games for Finland’s national team, including 11 World Championships and three Olympics, and he holds the Finnish record for the most international goals with 101. He’s one of just 21 players worldwide to appear in 100+ World Championship games.

Oksanen was such a legend in Finnish hockey that the Finnish Liiga named their MVP trophy for the regular season the Lasse Oksanen Trophy.

That leaves one to wonder what might have happened if Poile had loosened the purse strings a little and signed Oksanen back in 1970.

The expansion Canucks struggled to score in their inaugural season. Phil Esposito led the NHL with 76 goals and 152 points in 1970-71; Rosaire Paiement led the Canucks with 34 goals, while Andre Boudrias had a team-leading 66 points.

Could Oksanen have made a difference? It’s hard to say. He would have been the first player to make the jump from Finland to the NHL and it’s impossible to know how well he would have handled that transition.

When Matti Hagman became the first Finnish-born-and-trained player to play in the NHL six years later, he didn’t dominate, but he held his own. He finished his career in North America with 201 points in 290 games split between the NHL and WHA.

Maybe Oksanen could have done something similar, providing some extra skill to a team that desperately needed some. He certainly couldn’t have hurt.

Others saw the decision as a bit more detrimental.

“The decision not to hire him just may have been the first in what grew to be a long list of mistakes,” said The Sun’s Jim Kearney in 1974.

It took until 1984 for the Canucks to finally sign their first Finn, and he quickly became one of their biggest stars. Petri Skriko was drafted by the Canucks in 1981 and made his debut in the 1984-85 season, then led the Canucks in scoring in his second season, putting up 38 goals and 78 points in 80 games.

Skriko scored 30+ goals in four straight seasons for the Canucks, and he is still 17th all-time in career goals for the Canucks.

While Skriko’s star faded after that, he set the stage for other Finnish players to join the Canucks in the future, like Jyrki Lumme, Sami Salo, and Kevin Lankinen.

The Canuck who went to Finland

Oksanen didn’t earn a contract with the Canucks out of his trip to Canada, but he did ultimately steal a Canuck from Canada.

Len Lunde was one of the top players for the Canucks in the WHL before they joined the NHL, and stuck with the Canucks for their inaugural season, though he played in just 20 games. He apparently made quite the connection with Oksanen at training camp, however, as the Finn convinced Lunde to come to Finland for the 1971-72 season.

“Ilves shocked the hockey world by hiring Canadian forward Len Lunde,” reported Tapani Salo in Aamulehti. “Oksanen had met the NHL veteran at the Vancouver camp and was able to recommend him to Ilves’ bosses.”

Lunde didn’t just play with Oksanen for Ilves. Shortly into the 1971-72 season, head coach Juhani Ruusunen was fired, and Lunde replaced him as player-coach.

“Lunde was a completely different player than [Carl] Brewer,” said Oksanen, referencing another Canadian player who had come to Finland as a player-coach a few years earlier. “He was a good skater and had a good shot. What they had in common was that they both advocated a straightforward style of play. Lunde advised not to go to the corners and spin, but to just go straight to the goal.”

Lunde and Oksanen led Ilves to the Finnish championship that season, and Lunde remained as coach for Ilves without playing the next season as well. Lunde was then the head coach for Finland at the 1973 World Championship, where they finished fourth, just outside of the medals.