B.C. Premier David Eby has poured cold water on the formation of an independent anti-money laundering (AML) commissioner responsible for monitoring risks and the government agencies tasked to combat them.

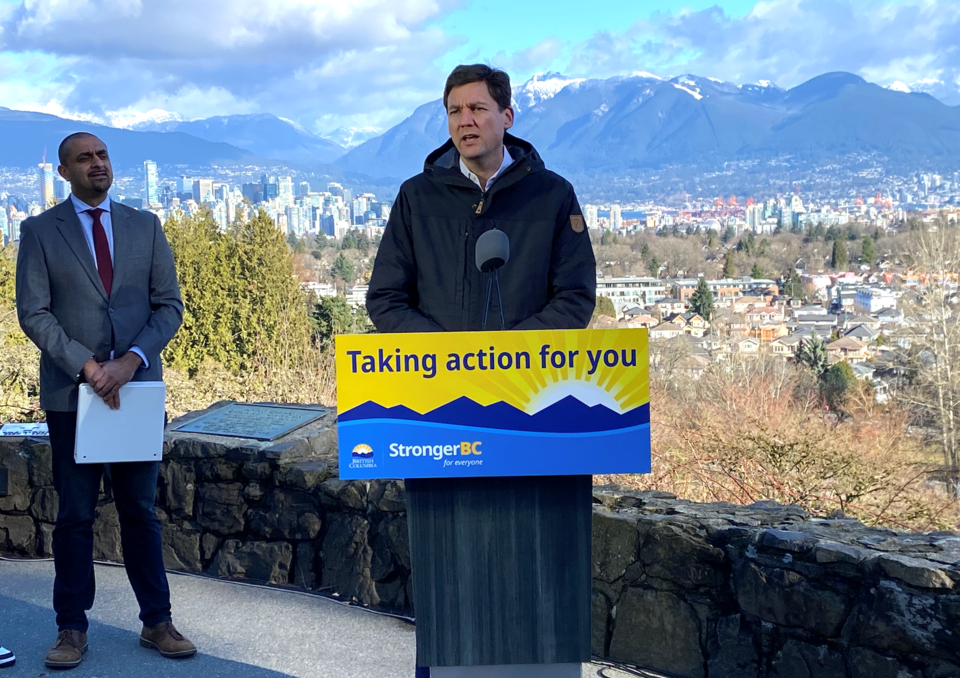

“We don’t have any imminent plans around establishing a money laundering czar (commissioner) but we are working closely with police, the Ministry of Finance, Revenue Canada and the land title office to make sure that information is as available as possible and effective as possible in fighting crime,” Eby told Glacier Media at a press conference Monday with Housing Minister Ravi Kahlon.

Eby held the conference to provide an overview of his government’s recent housing policies aimed to combat speculation, namely the new house flipping tax proposed in the 2024 budget.

The tax is to be imposed on a sliding scale of up to 20 per cent of capital gains on all residential property sales (and condo assignments) made within two years of an initial purchase. Exemptions are bountiful, including death, divorce, changes to employment and family membership and for renovations/construction that add at least one additional unit.

House flipping was considered a means to launder money in real estate, the Commission of Inquiry into Money Laundering in B.C. heard from experts between 2020 and 2022.

When asked if the commission informed his decision to implement the tax, Eby said, “There is no question that flipping activity was identified as a serious issue in the money laundering public inquiry as well as some investigative journalism, including issues like shadow flipping.”

But when asked about the status of creating a commissioner Eby said his government has taken alternative paths with other recommendations, such as a new unexplained wealth orders regime via civil forfeiture and more robust mandatory identification measures when buying and selling a home, including a new beneficial ownership registry.

“And,” said Eby, “new agreements with the federal government around tax information has enabled us to better enforce our own tax rules and enabled Ottawa to better enforce their tax rules.”

Establishing the “Anti–Money Laundering (AML) Commissioner” was the first recommendation of Austin Cullen, who headed the inquiry and whose 101 recommendations were outlined in his June 2022 final report.

Among key tasks, the AML commissioner was to be responsible for “monitoring, reviewing, auditing, and reporting on the performance of provincial agencies with an anti-money laundering mandate,” while “undertaking, directing, and supporting research on money laundering issues in order to develop expertise on money laundering issues, including emerging trends and responses, informed by an understanding of the measures taken internationally.”

The AML commissioner was also to analyze data from provincial and federal government agreements for AML purposes.

Cullen also recommended the province implement a universal recordkeeping and reporting requirement for cash transactions of $10,000 or more, meaning all businesses would need to comply. And, the AML commissioner would have access to this data to produce reports for cabinet members.

After learning federal RCMP financial crime units were understaffed, Cullen recommended the AML commissioner “monitor the response to money laundering within the RCMP federal police service by seeking detailed metrics concerning the resources dedicated to money laundering investigations, the number of money laundering investigations undertaken by the RCMP, and the results of those investigations.”

In total, without the AML commissioner, at least 10 recommendations cannot be fulfilled as envisioned by Cullen.

An analysis from Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation provided to Cullen’s inquiry showed 28 per cent of all properties sold between 2005 and 2018 were sold within 12 months, and this excludes flipping of strata property pre-sale contracts. Activity was most pronounced in 2006, dropped significantly in 2009 and picked up in 2015. By 2017, seven per cent of properties had been flipped in less than 12 months.

Kahlon said he did not have readily available data on how many homes the tax could target but the Ministry of Finance estimates revenues of $45 million.

Eby said the flipping tax is “not a silver bullet” and the purpose is to eventually not have to require the tax.