Vancouver housing stock is contributing to a big gap in who faces the deadliest risks during extreme heat events, a new report has found.

The report, released by Vancouver Coastal Health Authority (VCH) Tuesday morning, analyzed how climate change is leading to health risks across the region — one that stretches from Richmond to West Vancouver and includes 1.2 million people.

Public health experts found wildfire is leading to spikes in asthma-related hospital visits. The report also found 75 per cent of people living in homes without an air conditioner experience temperatures beyond 26 degrees Celsius. That’s the threshold for increased risk.

“The existential threat to our population is climate change,” said chief medical health officer Dr. Patricia Daly.

Daly said the region also faced risk from drought, flooding and storms — all expected to intensify in the coming years, and lead to impacts on people’s health. One part of the report highlighted the persistent threat of drought and arsenic contamination on the Sunshine Coast, and a drop in Whistler's water quality after high rates of snow melt.

The impacts of future sea level rise on the region “remain uncertain,” while wildfire threat would remain a “persistent threat,” the report found.

Housing 'not really prepared'

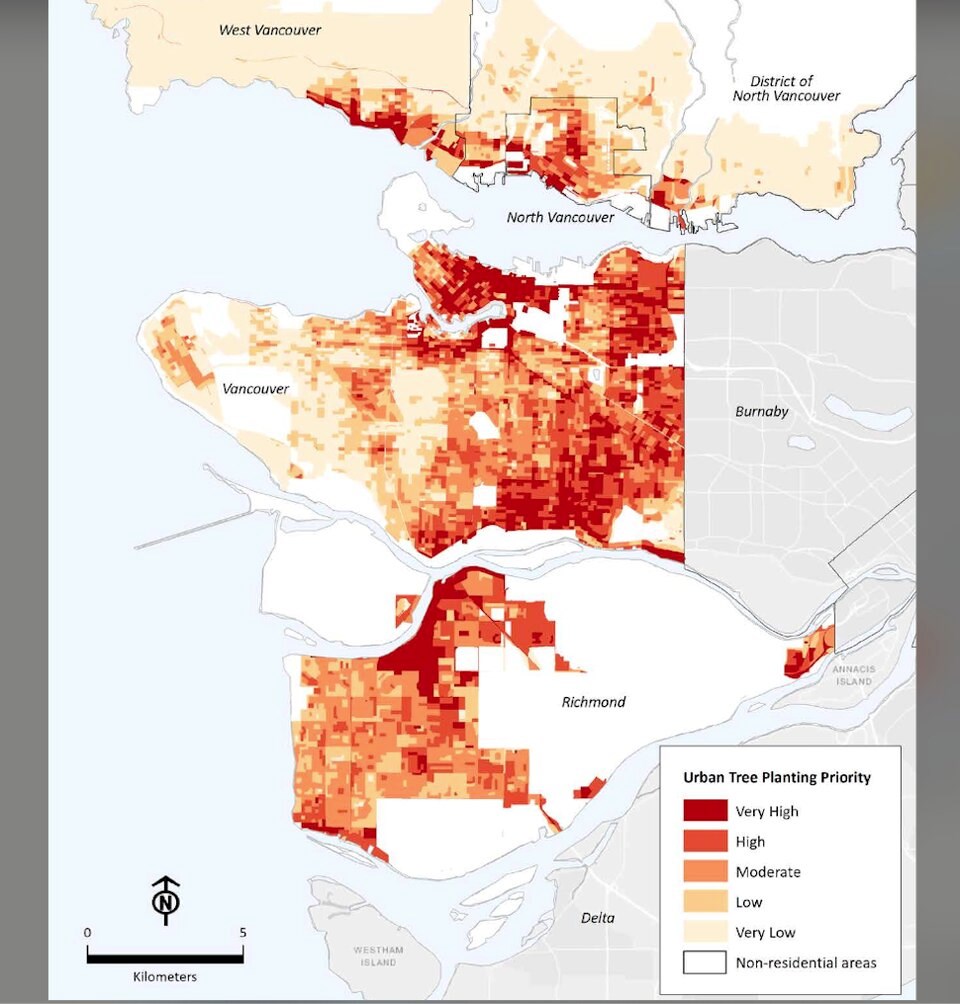

The authors of the public health report also reiterated how much green spaces protected people from the extreme temperatures of the heat dome in 2021, when temperature records fell across the province and at least 619 people died.

People who were socially isolated, older adults, those with preexisting health conditions, or who used substances impacted how people fared during the heat dome.

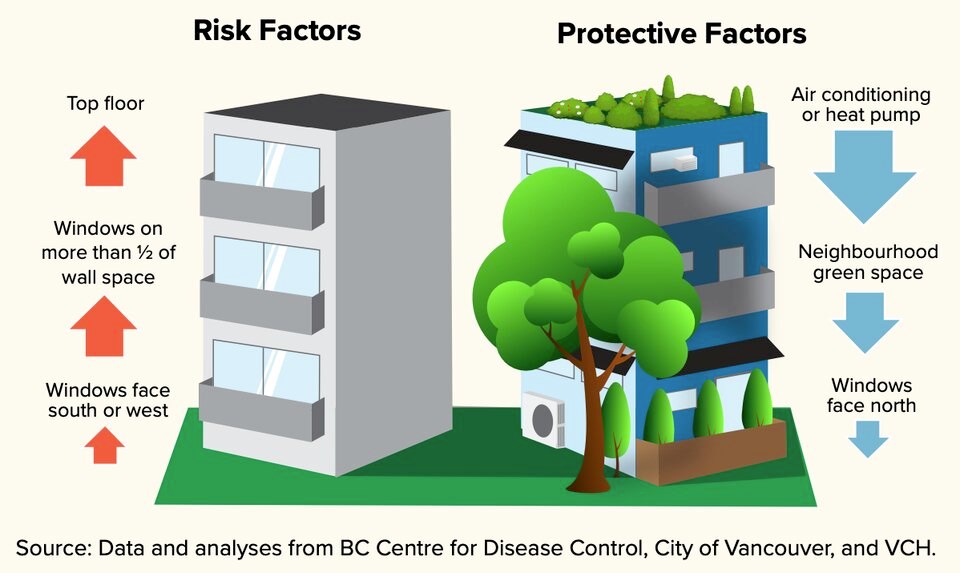

When asked what unique challenges the region faced, VCH medical health officer Dr. Michael Schwandt pointed to housing. Unlike other parts of the country where extreme heat was often a risk outdoors, in the Vancouver region, indoor air temperatures were the biggest killer.

“Our housing in our region is not really prepared for the climate that we’re seeing” Schwandt said.

The report pointed to scientific research that anticipates the region will experience extreme heat waves like the one in 2021 every five to 10 years by 2040.

Today, people on the top floors, with south-facing windows, and a lack of surrounding greenery faced elevated temperatures, the report found.

Heat-related emergency visits during the 2021 heat wave were highest in places like Downtown Vancouver, the Downtown Eastside, and parts of South Vancouver — neighbourhoods that tend to have relatively scarce tree canopy coverage.

Another factor leading to high emergency room visits were neighbourhoods where people were most economically disadvantaged.

Smoke a persistent and growing health threat

The report cited research showing that between 2013 and 2018, smoke from severe wildfire seasons led to 100 or more acute premature deaths in B.C. Another study from the University of B.C. found exposure to PM2.5 led to increased hospital visits between 2009 and 2019.

"Data on physician visits and dispensation of asthma inhalers showed that very high rates of these health-seeking behaviours occurred during times with increased PM2.5 due to wildfires," the report added.

Smoke vulnerability was found to be highest in the eastern reaches of Vancouver and Richmond, where "the population is more susceptible to the health impacts of smoke because of age or chronic health conditions, and where people are less protected by factors such as income, housing, or social supports."

Many remote and rural communities in the Vancouver Coastal Health authority are missing full-scale government air-quality monitoring stations that could help understand the impacts of wildfire smoke, the report found.

Recommendations bring a message 'of hope'

Many of the recommendations in the report echoed previous climate adaptation measures put forward by senior levels of government.

One of those was a need to strengthen direct supports to individuals at highest risk from extreme heat, including check-ins with people living alone or with disabilities.

Another included creating cooler outdoor urban environments by planting more trees. While no budgets were attached to the report, one of the most expensive recommendations to protect people from heat was a call to retrofit homes with air conditioners, heat pumps or other cooling devices.

The report leaned on national data and surveys of students that found young people are especially vulnerable to climate anxiety. Daly said she was concerned with the psychological health of young people.

“We don’t want people not to have a feeling of hope going forward,” said Daly. “I hope this report will be one of hope.”

Daly said the health authority is looking to work with community groups to help promote health in the face of threats from climate change. One of the report's recommendations aims at investing in schools and grassroots community programs to help young people discuss and "empower youth to play active roles in climate change mitigation and adaptation."

All of those measures, said Schwandt and Daly, would require support from higher levels of government.