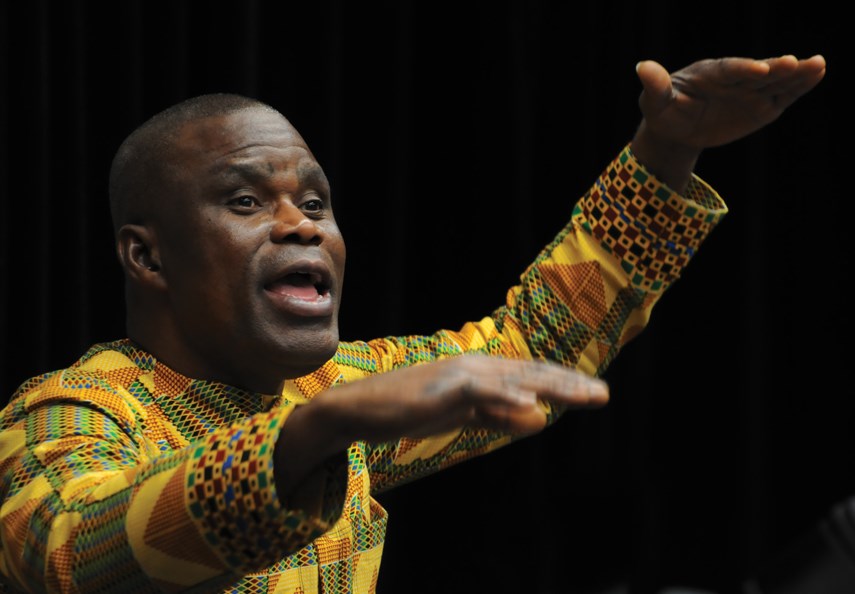

A Tribute to Africa with the CapU Jazz ensembles and faculty guests, featuring artist-in-residence Kofi Gbolonyo, The BlueShore at CapU - Birch Building, Jan. 25, 8 p.m.

He sings to them in Ewe, a tonal language spoken in southeastern Ghana.

He sings a long, graceful phrase. But for some of the student drummers assembled in the Capilano University music room, the phrase sounds impossibly long.

Everybody have it? Kofi Gbolonyo asks the class.

Answering loud enough to get a laugh and quietly enough to avoid detection, a drummer blurts: “No.”

Titters rise.

Gbolonyo repeats the phrase, adding a few more words.

Like a sketch artist guessing at a suspect’s facial features, the students manage an approximation of Ewe. The words aren’t right but they’re almost right. The difference, as Mark Twain pointed out, between the lightning and the lightning bug.

But then Gbolonyo starts playing the drum. The picture of ease and intensity, his drum calls out and the student drummers respond. It’s not too different from the interplay between Plant and Paige or Sam and Dave.

He sings that long graceful phrase again. The students sing back.

All of a sudden it sounds right.

The rhythm, tone and poetry of the Ewe phrase was waiting in the drumbeats of the song. The students can’t speak Ewe but they can sing it.

The rehearsal is in preparation for a Jan. 25 tribute to Africa concert featuring Gbolonyo and Dave Robbins on drums, Dennis Esson on trombone, Jared Burrows on guitar, Steve Kaldestad on saxophone, Brad Turner on trumpet and piano.

The concert is set to feature new compositions and traditional music from Ghana in what’s billed as an “exploration of African jazz roots.”

There’s a desire to incorporate Ghana’s ancestral music and rhythms into jazz, Gbolonyo explains.

“We’re trying to see how we can actually incorporate them into this mainstream jazz music,” he says. “North American jazz has a strong root in West Africa.”

According to music scholar Paschal Yao Younge’s book Music and Traditions of Ghana, there are approximately 46 ethnic groups in Ghana, each with their own distinct language. But in almost all of those languages, he writes, “there are no words to represent music, rhythm, or singing as separate activities.”

That seems evident as Gbolonyo drums, sings, and dances.

“You have to move your body,” he calls out.

Asked if he considers himself an ambassador for traditional African music, Gbolonyo, who earned a PhD in ethnomusicology from the University of Pittsburgh, questions the meaning of ambassador.

“If it means somebody that actually advocates and propagates, yes, I am,” he says.

He’s trying to preserve the music, he says. But that doesn’t mean locking vinyl records in a polyethylene fortress. The beats and melodies needs room to breathe and move. The music needs to be able to wind around and inside of the musical forms of today.

That fusion means presenting “traditional music outside of the tradition,” he says.

Growing up in Ghana, Gbolonyo observed the way seemingly segregated musical forms inevitably crisscross and cross pollinate.

“We got western music through the church and the school, and we got traditional music everywhere else,” he recalls.

Out of “sheer curiosity,” Gbolonyo began learning the trombone; one of the brass instruments left behind by German missionaries, he says.

He experimented. He applied the lessons he’d learned playing traditional music.

He didn’t know how to read music, but he knew how to listen, how to take in a song and play it back.

“My sight reading is very poor because of the tendency to try to memorize music quickly so I can play freely,” he says.

That tendency is evident at Capilano University as students play without sheet music in sight.

Bringing out the agogo, a bell instrument played with a drumstick, Gbolonyo sings the sound: “yup, yup, yup, do-do-do,” he croons.

“Got it?” he asks.

From there he adds an axatse, a gourd with a sound similar to maracas.

Looking for a volunteer, Gbolonyo exhorts his students.

“Come on, everybody here can play this,” he says.

He gets a volunteer and, sure enough, he can play it.

There are many ways into the music, Gbolonyo demonstrates.

One students asks about a certain riff. Is it like this, he asks, or this?

Gbolonyo sings it back one way, the correct way. Then he sings it a slightly different, equally correct way.

“Either way, you’re fine.”