Cranks, SFU Goldcorp Centre for the Arts, Vancouver International Film Festival, world premiere, Friday, Oct. 4, 1:15 p.m. viff.org/Online/f35962-cranks.

Before it joined “kook,” “crackpot” and “monomaniac,” the word “crank” referred to a bent handle.

But words, like work and thought, move with technology. And as the invention of the barrel organ allowed music lovers of the 1830s to hand-crank the same tunes over and over, the utilitarian word grew a new definition.

A crank, explains the Online Etymology Dictionary, came to mean an irrationally fixated person – perhaps the kind who would call a Winnipeg radio station and ask: “What is this world coming to?”

But who are these cranks? And how do these frequent callers fill their days when not being asked to turn down their radio?

Those questions fascinated writer/director Ryan McKenna, who hatched the idea for his black-and-white black comedy while sifting through a trove of Manitoba radio history.

From 1971 to 1998, broadcaster Peter Warren ruled Winnipeg’s radio waves as an: “all knowing force,” McKenna recalls. “If someone wanted to file their taxes and had a question about it, they would call Peter,” McKenna laughs.

Warren took calls, broke stories, and interrogated politicians while amassing a file of letters he stored in a folder marked: Cranks.

McKenna started reading. As surely as a radioactive spider, the letters represented an origin story. It was troll culture before there was a troll culture. It was before a horde of noxious content-mongers cultivated the internet’s swampy soil, back when Winnipeg’s collection of cockeyed conspiracy and hateful doggerel was confined in Warren’s folder like a vengeful genie.

McKenna picked six letter-writers from the file and imagined their lives.

There’s the guy who swears while lugging empty vending machines around a warehouse.

One woman writes a letter to Warren, asking: “Is love just an empty word now?”

And then there’s the rooms, which seem emptier when someone’s in them. As the film begins, the characters in Cranks could be on different continents if not for the bonds of the cold, the city, and voice coming from their radios.

Unlike Wolfman Jack’s accompaniment in American Graffiti or Lynne Thigpen’s coy threats in The Warriors, the radio in Cranks is a surrogate. These people need something but until they get it, they have Warren.

And as we listen to Warren banter about cults and post-Watergate political skepticism, we watch the characters and wait.

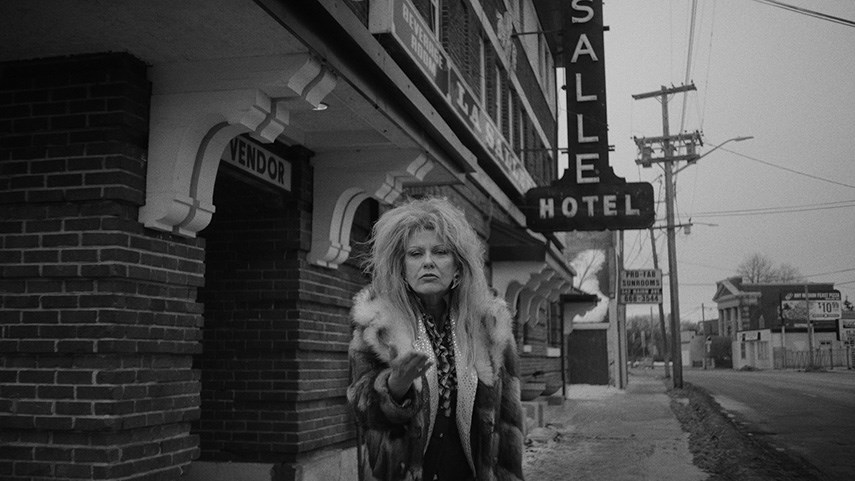

Marrying Ozu-like art house cinema and security camera footage, McKenna tends to use master shots, establishing a frame and capturing the characters moving in and out of it. The camera is a fixture. It was there before the characters and we sense it’ll be there when they leave.

In order to find the faces that matched the real crank letters, McKenna reached out to extras director Shelly Anthis.

“She just kind of knew everyone in town,” he says, explaining the need to find actors who seemed downtrodden.

It sounds gloomy but there’s a humour in Cranks, “that you wouldn’t get from a normal film,” McKenna reflects.

Discussing his inspiration for the film, McKenna cites John Paskievich, a photographer known for his brilliant, sometimes hilarious street portraits.

Winnipeg may have gotten more interesting and more colourful in the 11 years since McKenna moved to Montreal. But the old city is imprinted on his mind.

“Black and white is the way I think of the ’80s in Winnipeg,” he says.

There’s a story in there – even if you have to squint to see it. As we explore Winnipeg’s night life, one character touches another. It’s a gentle, grazing touch. But in a film where disconnection is the norm, McKenna makes it cinematic.

And Warren, despite his brusque bedside manner, engenders our sympathy in the film, if only because there’s no end to the vitriol directed his way. He’s a filthy, stupid, blind, hypocritical jerk, a “greedy selfish jealous stubborn little weak man,” who ought to be condemned like a dog, the cranks tell him.

But they keep calling. And until they find what they really need, they keep listening.