“The cinema has no boundaries – it’s a ribbon of dreams.” – Orson Welles, Los Angeles, 1970.

Citizen Welles – Robert Aiken’s firsthand account of working with legendary filmmaker Orson Welles on his last, unfinished film, The Other Side of the Wind, was first published in two parts in the Friday, Feb. 9 and Feb. 16, 1999 editions of the North Shore News. Recently completed in all its glory, Netflix will premiere The Other Side of the Wind on Friday, Nov. 2, along with a new documentary about Welles’ last years, They’ll Love Me When I’m Dead.

(Every word below was written in 1999 about what Aiken experienced in 1970 working with Welles):

North Shore News astrologer Robert Aiken did not always read the stars – for a brief period during the ’50s and ’60s he wanted to be one. At that time he worked in Hollywood under contract to 20th Century Fox as Ford Dunhill. Near the end of his stint in southern California Aiken got a chance to work with Orson Welles on the never-released film, The Other Side of the Wind. Welles’ daughter is reportedly trying to raise funds to restore the film and have it released.

Orson Welles became widely known in the late 1930s when his shockingly realistic War of the Worlds was broadcast over the radio.

At age 23, in Hollywood, he wrote, directed and starred in Citizen Kane, hailed to this day, as the best American film ever made.

Welles career continued with outstanding achievements in film, theatre and television. I’ll never forget him in The Magnificent Ambersons (1942), Jane Eyre (1943), The Stranger (1946), The Lady from Shanghai (1948), Macbeth (1948), The Third Man (1950), Mr. Arkadin (1955), Othello (1955), Moby Dick (1956), Touch of Evil (1958) (recently restored and rereleased), and The Trial (1963), his adaptation of Kafka’s classic of anxiety and anti-authoritarianism.

A highlight of my latter Hollywood days as an actor was being directed by the protean theatrical genius in The Other Side of the Wind, which is finally being completed by others as Orson is no longer with us. Shooting began on Aug. 23, 1970 in L.A. and continued intermittently through the spring of 1975, mostly in L.A. and Carefree, Arizona.

Welles began the production with his own money and continued with a succession of backers, including Les Films de L’Astrophore, an organization of the former Iranian government.

The only public screening of any footage, two brief clips, has been at the 1975 American Film Institute Life Achievement Award tribute to Welles.

The cast of the picture includes John Huston, Peter Bogdanovich, Oja Kodar, Lilli Palmer, Susan Strasberg, Robert Random, Edmund O’Brien, Cameron Mitchell, Mercedes McCambridge, Paul Mazursky, my good friend director Curtis Harrington, myself, Dennis Hopper, Henry Jaglom and Claude Chabrol. The story centres on a lavish birthday party given for aging film director Jake Hannaford (played by Huston), upon his return to Hollywood from retirement to direct one last film, a “hip” low-budget picture full of arcane symbolism, nudity and radical-chic violence. His picture, titled The Other Side of the Wind, is only partially completed.

While the party progresses, an associate screens footage for a studio chief who can’t make sense of it all. Hannaford, a legendary macho figure whose sexual and political attitudes have become archaic is both amused and repelled by the jealousy and adulation he provokes at the party.

The hostess, Lilli Palmer, has invited many important young filmmakers, critics, press people and camera crews from all over the world. (While the film-within-the-film footage from Hannaford’s picture was shot in 35mm, Welles shot the party footage in 16mm to give it the semblance of cinéma vérité material shot by the crews present at the party and visible in the film).

Among the younger crowd are members the “Hannaford Mafia” who recall bygone glory days while putting down the new generation. Hannaford’s ambivalent relationship with a successful young, rival director, played by Bodanovich, is unravelled during the evening, as is the old man’s fixation with the young lead actor of his unfinished film, Robert Random.

The silent, scantily-dressed actress in the film, Oja Kodar embodies Hannaford’s fantasies about women, while his deeper sexual attitudes are sarcastically analyzed by a female critic, Susan Strasberg, who argues with the Bogdanovich character and the author of an adulatory book on Hannaford.

As drink, passion and jealousy show their effects, the partygoers see the final act in the Hannaford legend unfold before them and learn that there is more to the man than meets the eye.

Prior to landing the role of a “left-wing radical” in the picture, I had become a serious astrologer as well as a motion picture actor (under the stage name Ford Dunhill) such as Up Periscope and This Earth is Mine. I had been writing screenplays and had written, directed and appeared in several experimental films. I was under contract, for a time to 20th Century Fox, and also appeared in Who Has Seen the Wind, Youngblood Hawk, Viva Las Vegas, Games and others (including Russ Meyer’s outrageous, at the time, Vixen).

In September, 1970, Orson Welles was, once again, the subject of heated controversy and counter-accusations between Peter Bodanovich, Orson’s “official” biographer and mouthpiece, and the Australian journalist and critic, Charles Higham, author of The Films of Orson Welles, a labour of love, of which, nevertheless, Welles, and therefore Bogdanovich, disapproved.

Meanwhile, Orson “seemingly” oblivious to it all, was in L.A. busily shooting the first picture he had made in America since Touch of Evil in 1957.

Still the “bad boy” of Hollywood, Welles was shooting secretly, non-union, with his own funds initially (doing an occasional guest stint on TV’s Dean Martin Show and Laugh-In to help pay the bills) with a crew of four and occasional help from their wives and trusted friends.

He was trying his utmost to remain unobtrusive (Orson Welles … unobtrusive?) on the streets of downtown L.A. and Century City and in and around his rented home amid three fortuitously located vacant and secluded lots far back in the smog enshrouded hills of Beverly.

The working title was The Other Side of the Wind. No one had seen a script. There was none. “It’s all in my head, Gary!” said Orson to his cameraman, Gary Graver, a young, eager, versatile non-union picture maker who had been making sex-exploitation films and receiving good notices for his excellent cinematography.

Gary, who Orson endearingly referred to as, “Gary Grab-it,” a typical Wellesian witticism designed to remind Gary of his “sex-oriented movie” days, was and always had been an ardent admirer of Orson and everything to do with Orson. He was the proud owner of 16mm prints of Touch of Evil and the I Love Lucy Show, on which Orson once guest-starred, which he more than occasionally screened for his friends.

In July, Gary had read in a Hollywood trade paper that Orson Welles was in town for a few days. He hurriedly called The Beverly Hills Hotel, boldly asked to speak with Mr. Welles, got through to him and proceeded to bemoan his lot as a maker of “X-rated” films and offered … “to work with you … here or in Europe, even … I’ll pay my own way. Anything for a chance to work with you.”

Silence. A bit of incoherent grumbling was heard, then: “Could you be over here in 10 minutes?”

Within five minutes, Gary had joined his idol for a mighty drink and enthusiastic conversation about specific scenes in Citizen Kane, Touch of Evil, Falstaff, The Trial, but mostly, about his own prowess as a low-budget picture maker – how he once managed to bring in a feature for the impossibly low sum of $10,000. And about how he had the most efficient little crew in town and, again, offered his services for nothing (which he could little afford to do). This, of course, impressed Mr. Welles.

“You’re bright! I have a hunch about you. I’m going away for a week, but I’ll be back and we’ll make a picture together. Say nothing about it to anyone.”

Gary, ecstatic, told a few trusted friends, including yours truly, also a film enthusiast and an admirer of most of Welles’ work. He ingeniously related: “It’s the culmination of a life-long dream! And he’s a regular guy! Laughs at lot … at his own jokes, mostly. A groove. Really, beautiful!”

He then proceeded to imitate Welles as Hank Quinlan (the character he played in Touch of Evil): “Vargas! Vargas!” He had a fit of laughter.

I, having previously attempted to contact Welles regarding a screenplay, decided to try again. “Think I could be your still man, Gary? Anything at all? I want to work with him in some capacity.”

Gary would presumably hear from him within the week. We excitedly left it at that.

A few weeks later, I heard that Mr. Welles had returned and that he and Gary were, indeed, actually busy preparing to shoot film. I rushed to the Beverly Hills Hotel in hopes of finding Welles in the Polo Lounge. There he was, formidable, bear-like, in there with an agent and friend with whom he was conversing in laboured French and, occasionally, laughing boisterously at his own quips, just as Gary had said he was wont to do.

I seated myself nearby, undertook to write a note of introduction and found myself ordering a succession of beers over a period of two fascinating, eavesdropping hours.

To the agent: “Is it in escrow?” Repeatedly, “Is it in escrow? Just get the money in escrow!” To his French friend: “You have just mentioned one of my pet hates. That publisher and his school for writers.”

He was genuinely upset. “Bah! You would think he had enough money … Imagine! Exploiting poor, aspiring kids who cannot even write their own names!”

He shook his head in disgust as he lit a monstrously huge cigar which threatened to envelop the entire threesome in billows of thick, grey smoke. He then politely made a half-hearted obviously futile gesture to brush the smoke from his friends’ already obscured faces.

His deep voice carried. People at the extreme far end of the room could not help but know that he was there.

His presence was in fact so compelling that I found it difficult to concentrate on my note of introduction. When they left, leaving Orson sitting there alone, I tentatively handed him my note with a manila envelope (pictures and resumé). He looked me over intently with his huge, watery eyes (his Jupiter in Pisces, I had studied his astrological chart), and said, “Don’t just hand me an envelope! (in mock anger) … C’mon over here and have a drink with me!”

(To make a long story short, we “jump cut.” Later, on the set …)

Orson somewhat somnambulantly began: “The story is about Jake, an old movie director … someone like Huston. I may use John Huston. He, unlike me, likes to act. And he’s right for this. Jake is on a masculinity trip. Kind of mean, hard. He’s making this movie, the movie within the movie that you’ll be in Bob. (I had long since given up on the name Ford Dunhill). His obsession with the boy’s pursuit of the girl and his realization that he is really identifying with the girl and …”

I interrupted. “He comes into conflict with his androgynous …”

Orson brightened at the the use of this particular word. “Yes! That’s it!”

We all bobbed our heads up and down in light-hearted mutual agreement. “Yes, of course. His essential androgynous …’ He trailed off. He loved words and he almost demanded that people be “specific” when conversing with him.

“Why don’t you play the director?” I asked.

“No, not right. Not old enough,” he said. “Not the right quality. And they would say it’s me and all that … it simply should be someone else.”

I suggested Sam Fuller. “Not a bad idea, but …” Someone says he’s too short. Orson agrees. “Good director, though!” Some small talk. “No, it’s not like 8½” This had become tiresome for him. He, obviously, like most creative people did not like to talk about a work in progress. And, later, I heard him tell Oja, the leading lady, that he must tell a story well or not bother to tell it at all. He simply wished to tell me a few essential things about my role and leave it at that. He was suddenly in a mood that I was to observe come upon him later. Still centred. Seemingly about to erupt and, perhaps, devastate everything in his space, which included much territory. Orson Welles’ space was considerable and he owned it and, usually, that of everyone else within eye and earshot.

(Later, during the shoot …)

“Orson … not long ago there was an issue of Esquire Magazine that featured an article about Robert Graves. Did you see it?”

Orson, genuinely surprised, stopped short, lit another foot-long cigar and confronted me. “How did you know I liked Robert Graves?”

I replied: “I know about you. I read it in an interview with you somewhere … but you would have affinity with that ’guerrilla classicist,’ wouldn’t you?”

I had also seen a copy of Graves’ Love Poems among Orson’s newly acquired books. We walked further up the hill toward the vacant lot where Gary and crew had hopefully, set up the next shot. Orson beamed. “He approves of me, you know…” I asked, “Ever meet him?” Orson, with gusto, “Never laid eyes on him. We have mutual friends. I don’t have to meet him. Best not to ruin our friendship by meeting him.”

(Another recollection: Early morning. Centre divider of Santa Monica Boulevard before the great, modern office buildings of Century City.)

Welles, feigning invisibility, cowering before every passing car, but in fact cutting an impressively, mighty, Jovian figure amidst the heavy fog – directed Gary, Michael, Glen and Gary’s wife, Connie, as to what to do and, specifically, how to do it.

Holding up traffic, ready to run at the slightest danger of being caught, shooting without a permit, he cracked, “If they catch us we’ll just say that we’re testing emulsions, Gary!” His thunderous laughter was not unobtrusive.

Another anecdote comes to mind: Orson, watery eyes twinkling, related the ominous story: “We narrowly eluded the police. They were chasing us. We were shooting behind the bank early the other morning. Michael tripped the burglar alarm with the tripod – clumsy boob!”

His entire being was suddenly convulsed with laughter. “They were actually chasing us!” No one quite enjoyed the adventure of working with Orson Welles quite as much as Orson, himself.”

A young man had the budget all prepared. Everything in order. Professional. Ready to be presented to a sponsor with, possibly, Orson Welles as part of the package. Orson told him: “This budget is way out of line. All this money for the cameraman? Ridiculous!” The young man was taken aback. “But he’s a great director of photography, Mr. Welles!”

Orson started. He was appalled, or seemingly so. “Director of photography? It was cameraman in my day.” The youth was unnerved and apologetic.

Orson muttered on disapprovingly. “Director of photography, indeed. He costs too much. He’s not good if he costs that much money. If he costs you nothing, he’s good.”

The young man was shocked. “You actually mean to say, Mr. Welles, that he is automatically good if he’s cheap?” Orson’s attitude had suddenly completely changed and he simply stated, “If he costs nothing, he’s good.”

One evening at a Mexican restaurant in Beverly Hills: Janice wanted to leave her manager because he had done nothing for her modelling career. Orson advised: “Never, never give reasons. Just say, ‘I want a new manager.’ No reasons! No service contract is binding. Otherwise it’s slavery. Just say ‘I want out or I’ll see my lawyer.’ They’ll say ‘Try and be reasonable … intelligent.” You say, ‘I have no obligation to be intelligent. I’m just a dumb, rather stupid actress. I want out … that’s that.’”

Later on he said: “Don’t be honest with them … agents, managers … all those exploiters. They’re not honest with you. ! Tell them you just played a starring role in repertory theatre or something in South America with Leopoldo von Edelburg … anything!”

“I didn’t want to be an actor,” he would say. “I needed money. Had I gone to Dublin and asked, feigning meekness, ‘May I work with you and your company in some capacity? Please?” He laughed. “That’s what I would have done … swept the stage or something. I told them I was a star.”

“Chutzpah! Got to have chutzpah!”

Gary Graver functioned as production manager, assistant director and cameraman. All equipment, film stock and various rentals were taken out in his name – a “Gary Graver production” with Orson running the whole show. Gary and his crew – Glen, Michael and Les – were on call devotedly, day and night, as were we.

The man that many considered to be the greatest theatrical genius of our time abhorred being called a “genius.”

Dennis Hopper, years ago, had approached him and enthusiastically spoke to him of his great genius and Orson cried angrily, “Don’t call me that! I hate it!” When Dennis related this to me, I suggested that he could have retorted, “But, Orson, I’m talking about me!” He liked that, but would not have dared.

During rushes: “This shot is no good. No magic there. Anybody’s movie!” Later, on the set: “Yes, stay there. You’re not in the shot, but we ‘feel’ you there. Let us ‘feel’ you.”

After rushes: Somebody said, “Antonioni never got shots like that!” Orson began to rumble with imminent, sardonic laughter … “You bet your sweet ass he hasn’t.” He considered Antonioni’s films “empty boxes.” (Note: Many critics consider Antonioni’s L’Avventura to be the greatest picture ever made).

Orson changed his mind constantly. He would never accept there was a problem. If there was an obviously insurmountable obstacle, he immediately decided to do it another way. Invariably, a better way.

Interestingly enough, Russ Meyer worked in a similar manner and I had found him to be just as brilliantly resourceful and inventive as Orson (in some respects).

Orson was unpredictable. One moment he was angry. Next moment: “I have an idea!” And with that, he had then completely “died” to the previous moment and was totally and creatively into the new, the fresh, the unique.

I recall him saying: “If there is a profession/vocation to directing, which I doubt, it is the ability to use accidents.”

I challenged that (I was a bit of an upstart): “There are no accidents, Orson! You mean ‘serendipitous moments,’ probably.” And on and on we argued good naturedly about that one.

“Of course, I would not be able to get as much coverage shooting any other way. This is the only way to shoot. I much prefer a crew of four and lots of time.”

We had been shooting at Century City at odd hours, day and night. I would be awakened at 4 a.m. “Be there … 20 minutes!” One morning, the weather wasn’t right. “Then we’ll simply get some smoked glass and recreate Century City right here in the dining room.” And he did. The footage was astounding.

I remember well: 2 a.m. We were in the middle of one of the three vacant lots adjacent to our headquarters, Orson’s rented home.

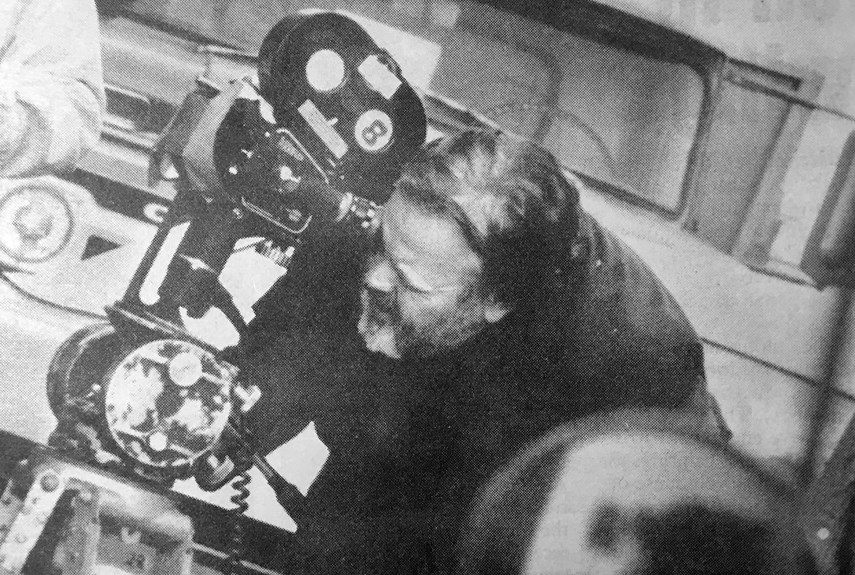

“God damned machine,” he frustratedly bellowed through his cigar as he, pyjama clad, scotch in hand, struggled in vain to position his huge frame low enough to see through the viewfinder of the Arriflex camera which was placed impossibly low and tilted for one of his famous, bizarre wide angles of, in this case, we three actors in the stationary car. He finally left it to Gary. “Looks good to me.”

Orson referred to me, “Bob, you’re driving at 80 m.p.h. and you pretend to ignore the lovemaking of Oja and Robert next to you. And no ‘kabuki’! Just think it!”

He addressed Oja, the girl: “Oja … you are straddling Robert Random and making love as though you were alone with him in the car … open your dress a little more, dear … let’s see more of you.” Oja revealed more of her nude body beneath the raincoat.

Orson whooped, “Russ Meyer rides again!” This broke everyone up, not the least, Orson. After a few comments about Meyer, Hollywood’s King of the Nudies, Orson gracefully intoned, “Ready to go, Gary?”

Gary, prone and pretzel-like hollered excitedly, “Looks good to me!” Michael then turned on the backseat sun gun and hurried to the key and flooded the windshield with light. “Rain!” thundered Orson. Glen fumbled with the hose. “Hurry … hurry!” Orson impatiently blared. We are ready to go now. Orson is in his “no-nonsense” mood.

Glen finally turned the hose on the windshield. Orson cried, with mock bewilderment: “Where are the streetlights, buses and other cars?”

Gary’s wife, Connie, began to move the red and yellow gelatins slowly back and forth before the backlight. Then Orson sat on the back of the car and with obvious ease rocked it violently. “Action!” he clamoured. “Action!” The scene could not have been more amusing if he had been wearing diapers.

“I was awake all night. Ideas!” He looked at me slyly. “We’re nearing the full moon, right?”

I think fast: “Yes, tomorrow.”

Orson replied: “Yes, thought so. Always get all these ideas around the full moon. I have many new ideas for the picture.”

Later, I ventured to bring up astrology once again. “Orson, you do have the moon in Aquarius, conjunct the ruler of Aquarius, Uranus, and the moon.”

He tensed. I hesitated and stopped. He didn’t really approve of my knowing that.

Orson looked at me seriously, “I’m clairvoyant, you know.”

Orson had initially expressed concern that since I was such a “nice, good looking” guy I might not be right for the role. Later, after rushes, I asked him how I was coming across. “Dynamite!” he thundered. I was pleased.

I found the great man did not so much “direct” as “evoke.” He was a great magician. He would incant. He managed to raise up things that were not really there. He always spoke of the shot or footage in terms of magic or poetry. Orson at work: “Never mind the logic of it. Just do it.”