Design for Living: West Coast Modern Homes Revisited. West Vancouver Art Museum. Until July 13 (westvancouverartmuseum.ca).

On the crest of a hill in West Vancouver there’s a home with a view of Altamont Beach Park.

It’s not a birthplace exactly; because what would we write on the certificate? After all, there’s no single moment when the architectural movement known as West Coast Modernism was born. But if there’s a place where a collision of ideas loosed a generation’s sense of architectural invention and harmony, it happened on that hill.

The evolution of West Coast Modernism – from Berlin to Mathers Crescent – mirrors the journey of the generation of refugees who fled the evils of fascism in the 1930s.

While Vancouver was building gable-roofed clone homes that could only be differentiated by the cars parked in front of them, the first stirrings of a new architecture were happening in Germany.

With an aim of harnessing mass production for the benefit of mass society, the Bauhaus school of arts flourished in the 1920s.

The school’s director, a Swiss architect named Hannes Meyer, favoured: “concern for the public good rather than private luxury,” writes scholar Alexandra Griffith Winton.

That idea would endure Nazis. The school couldn’t.

Amid rumours the students and faculty were producing anti-Nazi propaganda or were linked to the communist party or both, the Bauhaus school was shuttered in 1933.

But the school had already become a “global cult, sending out . . . eager young missionaries to spread the modernist word: honesty of construction, death to decoration,” according to the book Mies in Berlin.

One of those young missionaries was Austrian born Richard Neutra.

A schoolmate of Sigmund Freud’s son and an admirer of Frank Lloyd Wright, Neutra dashed to California – where Orson Welles and Ayn Rand made use of his designs – and back to Germany where he became a teacher at Bauhaus shortly before its closure.

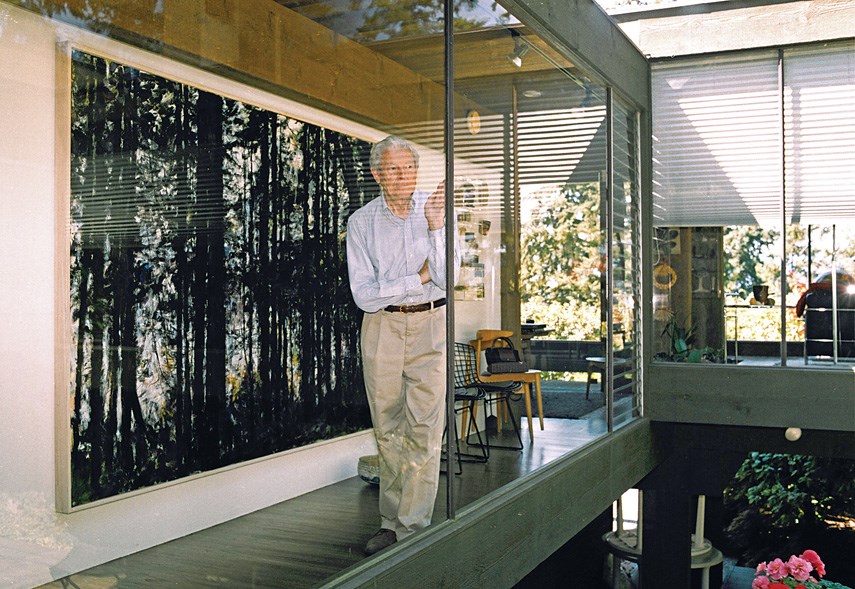

Neutra cultivated designs “that linked the indoors with the outdoors, emphasizing natural light and the relationship of the building to the landscape,” writes West Vancouver Art Museum curator Darrin Morrison.

That approach intrigued young architect B.C. Binning, who arranged for Neutra to visit his home on the hill at 2698 Mathers Crescent in West Vancouver

It was after the Second World War when people were seeking a return to normalcy and paradoxically “looking to break the bonds of the past,” Morrison says.

Before a group that included future luminaries Arthur Erickson, Barry Downs, Peter Thornton, Fred Hollingsworth and Ron Thom, Neutra discussed “the mystery and realities of the site.”

Whether his words were a confirmation or a revelation, the architects in attendance formed the crux of a movement that would transform Vancouver from an “Edwardian backwater

. . . into the beginnings of a cosmopolitan metropolis,” according to UBC professor Scott Watson.

Explaining his philosophy for design in the 1960s, Thom suggested architects should create “not what is acceptable but what will become accepted.”

That philosophy is still on display in a bungalow just below the highway near Ridgeview Elementary. The Carmichael Residence, notes architectural writer Adele Weder, is built on a hexagonal, rather than orthogonal, grid. “The diagonal trajectory makes for a whirligig circulation pattern, as though one is walking through a continuous Mobius strip,” she writes in Design for Living, the book complementing the museum’s exhibit.

Amid a gargantuan fireplace that “evokes the hearth of a medieval castle,” there are strong influences from Neutra and Wright in the home, according to Weder.

The Carmichael House came on the market in 2011, which, for many heritage homes, is a stop on the road to obliteration.

But instead of swinging a wrecking ball, Jan Pidhirny and Jim Ferguson saved the house. They added some drywall, replaced the glazing, moved the front door and dismantled the original kitchen.

They changed the house as little as possible while “bringing it into the 21st century,” Weder writes.

The Carmichael Residence offers an example of the way an architectural landmark can be altered without being erased, Morrison notes.

“What we really wanted to show is how examples of modernist homes can be preserved through renovation, restoration and adaptation,” he says. “I just think it’s really important for people to come and experience the efforts and energy of homeowners and designers and architects who’ve lovingly restored their homes.”