Public safety has never been more in the forefront of all our minds.

In the midst of a global pandemic, we are all encouraged to think of the greater good, to stay home and stay safe, to take care of ourselves so that we may take care of others. Which is why, as this column goes on hiatus for the next little while, I wanted to leave you with the story of a time when you could order a rocket-propelled axle for your car through the mail.

The year was 1962. America was obsessed with rocketry and the potential of towers of flame, propelling us all towards the stars. The interstellar adventures of Star Trek were just a few years away, and popular science fiction promised a time when anything would be possible.

Enter Florida, that crucible of bad ideas and poor parental supervision. Eugene Middlebrooks Jr., then in his early 30s, was a mechanical engineer working on propulsion systems for the Pershing nuclear ballistic missile systems. But Middlebrooks wasn’t content to be merely a cog in a machine. He wanted more.

The key ingredient to Middlebrooks’ plans was N-propyl nitrate, better known as the essential propellant in a solid rocket booster. Needing no atmospheric oxygen to combust, N-propyl nitrate was ideal for both the space race and the concept of mutually assured destruction. Ol’ Gene started thinking about how to adapt it for cars.

He’d already had a go at an idea that was just ahead of its time: the electric supercharger. Interested in racing, specifically drag-racing, Middlebrooks knew that bolt-on upgrades would be a hot seller for anyone looking to get an edge on the driver next to them at the staging lights. Due to the weight of batteries and technical problems, he couldn’t get the electric supercharger to work.

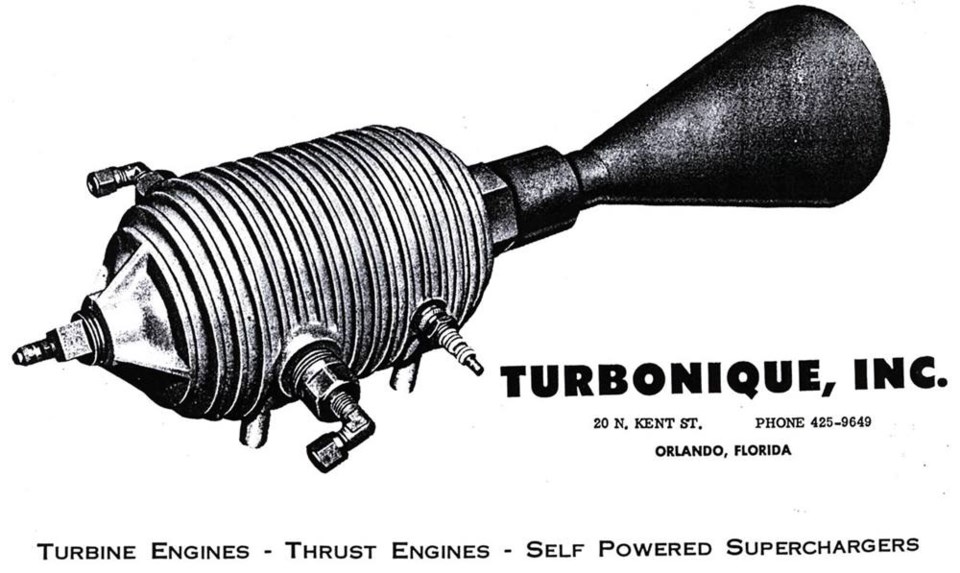

So he brought his work home with him. Turbonique, Middlebrooks’ company, was founded in the early 1960s with its first product, a rocket-powered supercharger.

Superchargers and turbochargers operate on the same basic principle. Since any internal combustion engine is essentially an air pump, ramming more air and fuel into the engine means more power. While turbochargers scavenge exhaust gases to spin their fans, superchargers are usually belt-driven off the engine.

Not Turbonique’s solution. Instead, the Microturbo thrust unit was a sort of Catherine Wheel firework attached to a turbine. Hit a button that sparked the propellant, and the supercharger kicked off at up to 100,000 r.p.m.

How much power are we talking? Well, this was the early 1960s, when factory hot-rods like the Pontiac GTO made just over 300 horsepower from a 6.4-litre V-8. Turbonique promised up to an additional 850 h.p. from their supercharger.

That, obviously, is an insane amount of power. Imagine pushing a button and instantly more than tripling the power of a car that was considered one of the most muscular on the roads. Even by today’s standards, that kind of power is like suddenly getting rammed by a Dodge Challenger Hellcat.

Of course, Turbonique’s mail-order business model wasn’t exactly confidence inspiring. In the days before Amazon reviews, you sent away for your “X-Ray Specs” and you ended up slightly disappointed. However, Turbonique actually made some proof-of-concept vehicles.

One notorious machine was the Black Widow, a humble Volkswagen Beetle. It came equipped with one of Turbonique’s other offerings, the drag-axle.

The drag-axle was simply the same idea as the rocket-propelled supercharger, now applied directly to the rear wheels. When you pushed a button, the fuel would spin a gear attached to the rear axle, and the car would shoot forward. The bolt-on part was made of aluminum, and weighed around 50 kilograms.

When activated, it added a claimed 1,300 h.p. to the output of that VW Beetle. I’ll say that again. One thousand, three hundred horsepower. Never mind how crazy that was in 1966, imagine the insanity of mashing that button today.

The Black Widow ran through the quarter-mile in 9.36 seconds, which is two seconds faster than a Ferrari Enzo. One one thousand. Two one thousand. That’s by how much a humble little economy car just smoked the pride of Maranello.

Now, you may be thinking to yourself, “But why have I never heard of Turbonique before? Were there any drawbacks?” Well, that depends. Is a horrible fiery explosive demise a drawback? I suppose some people might think so.

Should you lift off the throttle after activating your Turbonique power adder, the fuel would pool in the housing, essentially turning it into a bomb. Touch the throttle again, and it’s explodey time.

So, once you light that candle, there’s no turning back. Further, adding that much power at the touch of the button obviously comes with some safety concerns. The Black Widow did manage at least one successful pass, but later crashed spectacularly at more than 300 km/h, flipping end over end as it crossed the finish line. Happily, the driver walked away.

We’re not quite done. Along with the drag axle and the rocket-propelled supercharger, Turbonique also offered outright rocket engines. These weren’t intended for application on a car, as that would be far too dangerous, even for them.

Instead, you were supposed to bolt them on a go-kart.

I once interviewed someone in Edmonton who successfully had a run (just one) in a Turbonique rocket-powered go-kart. It scorched down the quarter mile, easily beating a hemi-powered Dodge, and then nearly got run over at the end when the power stopped. The owner stuck the kart in a garage and never went near it again.

Sadly, the promise of Turbonique never quite lived up to their demonstrations. The parts were not as well-finished as promised, and required a great deal more machining than the average user could perform. They weren’t quite X-ray specs levels of hype, but they weren’t quite the bolt-ons that were advertised.

And then there was the problem with N-propyl nitrate, which Turbonique called Thermoline. Obviously mailing solid rocket fuel wasn’t going to last for long, and the substance was soon impossible to find. You could brew your own alternatives, but that wasn’t exactly safe either.

Thus, poor ol’ Gene Middlebanks found himself convicted of mail fraud, and Turbonique folded. Well, I say poor ol’ Gene, but he chose to defend himself and this was his third indictment for mail fraud and it doesn’t appear that any dissatisfied customers got any refunds. Receiving two years in prison and a fine, he got out of the mail-order game and ran a resort in Florida for the rest of his life. Nobody picked up the rocket-powered-car torch from him, possibly because they were worried about getting their fingers blown off. The end.

As we head into uncharted territory over the next few weeks, you’ll always be able to get sensible, local COVID-19 information here in this paper.

For now, however, I’m told the Friday edition will take a breather, and with it, this column. I hope to return as things get back to a new normal, and in the meantime you can find anything I write at brendanmcaleer.ca.

Stay safe out there everyone. We’ll see you soon. The road awaits.

Brendan McAleer is a freelance writer and automotive enthusiast. If you have a suggestion for a column, or would be interested in having your car club featured, please contact him at [email protected]. Follow Brendan on Twitter: @brendan_mcaleer.