In an unassuming shed on the evergreen slopes above Roberts Creek, weaver and entrepreneur Pam Magee is doing more than producing heirloom fabrics on century-old looms. Magee is also pulling strings to patch Canada’s reputation among the world’s textile-producing nations.

Magee founded the Macgee Cloth Company four years ago. A pharmacist by profession and a casual knitter, she was inspired after seeing a century-old loom in operation during a trip to Spain.

She enlisted the mentorship of a Yorkshire weaver who prefers to be known by his first name only. Howard was responsible for setting up the Spanish textile mill that caught Magee’s attention. He also revived 26 heritage looms now in operation in New Zealand.

Howard once worked under his father’s tutelage in Huddersfield, one of England’s preeminent textile production centres. As a teenager he oversaw maintenance of the machinery. He wrested his way into the tight-knit industry to work in some of the most prestigious weaving shops in the British Isles.

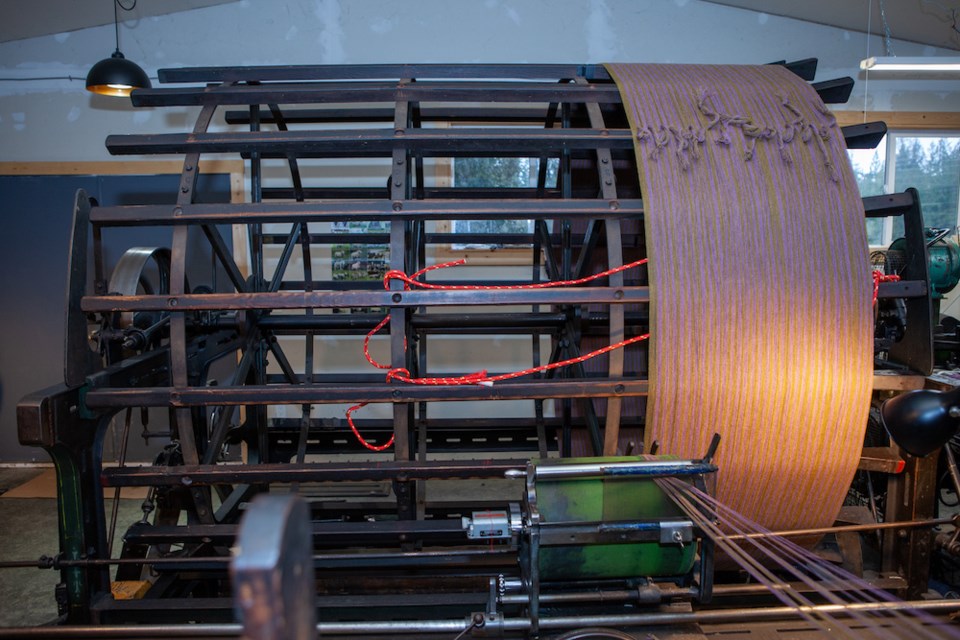

With Howard’s assistance, Magee acquired and imported a 1936 Dobcross loom. The wrought-iron behemoth had been languishing in a bricked-up warehouse in the Welsh countryside. Painstakingly reassembled and fitted for North American electrical current, the loom became the anchor of Magee’s cloth enterprise.

“Heritage looms like this are far superior to anything that has been produced recently,” said Magee. “It doesn’t mean that the fabric that comes off [new looms] is bad. But computerized rapier looms are built more for speed than finesse.”

The weighty gears of her octogenarian shuttle loom can be adjusted depending on the thread count of the yarn it processes. The finest wool, measured in the order of hundredths of a centimetre, produces the costliest cloth.

For Magee, the provenance of her yarn matters. She imports from family-owned spinning companies in Yorkshire which procure raw wool from sources practicing humane animal husbandry. Her organic cotton is gathered by a marketing cooperative in Texas before being spun in North Carolina. Each bale is marked with a number identifying the farm where the cotton grew, a U.S. practice unique among cotton-producing nations.

The success of Macgee Cloth—her blankets retail for $800 and more at Vancouver’s Inform Interiors and custom orders have doubled each year— shows an appetite for high-quality Canadian fibres, Magee believes.

Yet waves of outsourcing have unravelled the field of Canadian commercial weaving. “They offshored everything back in the seventies,” Magee said. “Even if you try to source Canadian wool, there’s nobody grading it. The Montreal textile people started applying labels saying Made in Canada when those products were never made in Canada.”

Magee tried to streamline her workflow by contracting with a domestic fabric finisher. An Ontario firm told her it wasn’t worth their while, since they were profiting by importing Chinese textiles, dying them, and marketing them as a Canadian product.

Dedicated to total integrity, Magee today elects to finish and wash the cloth herself, pressing the fabrics with an oversized Italian tailoring iron. She juggles production single-handedly while managing online marketing and social media accounts.

It’s time to start thinking about succession, Magee admits. But options are few in a country where textile traditions are no longer a dyed-in-the-wool component of domestic commerce.

“It’s too bad,” Magee said, “because there are a lot of kids who would really like to take this over.” She recently ran a hands-on field school for students from Emily Carr University of Art + Design. “They could really take the design to the next level,” she observed, “because they have the energy. Howard has said he would come over [from his home in Europe] and mentor somebody else to the next level, and it could be a new beginning. Canada could come back.”

Until then, Magee finds a balance amid the age-old rhythms of transforming carded wool into bespoke blankets, scarves, and travel rugs for customers around the world. Her Roberts Creek mill, stocked with bright-hued bobbins, is a combination of an industrial machine shop and polychromatic sanctuary.

She has supplemented the original 1936 loom with three other hulking units, including an American antique purchased from the textile artist who creates custom fabrics for Steven Spielberg’s movies.

Near the entrance, an 1895-vintage warper spins to create the skeletal strands that are slung across the loom bed. Its cogs and belts fly into motion as Magee launches the torpedo-shaped shuttle that guides the yarn, over-under, over-under, through the warp. A computer program advises when to change colours, producing intricate patterns from duotone houndstooth to broad-striped tartans.

“The loom is like a big metronome,” Magee said. “It’s quiet. It’s craftsmanship. You can listen to Bach. With my pharmacy work, it’s never done. But here, there’s something soothing about making something with your hands that comes to completion.”

Magee encourages a visitor to run his palm over a bolt of cashmere-soft cloth. In the shadow of the hefty machinery that wove it, the blanket’s surface is uncannily supple. Such stuff, as Shakespeare’s Prospero might murmur, as dreams are made on.