“I have this heaviness in my heart, this heaviness I have to carry until the day I die, and you want to heal the country, and you want to heal people around you,” he said.

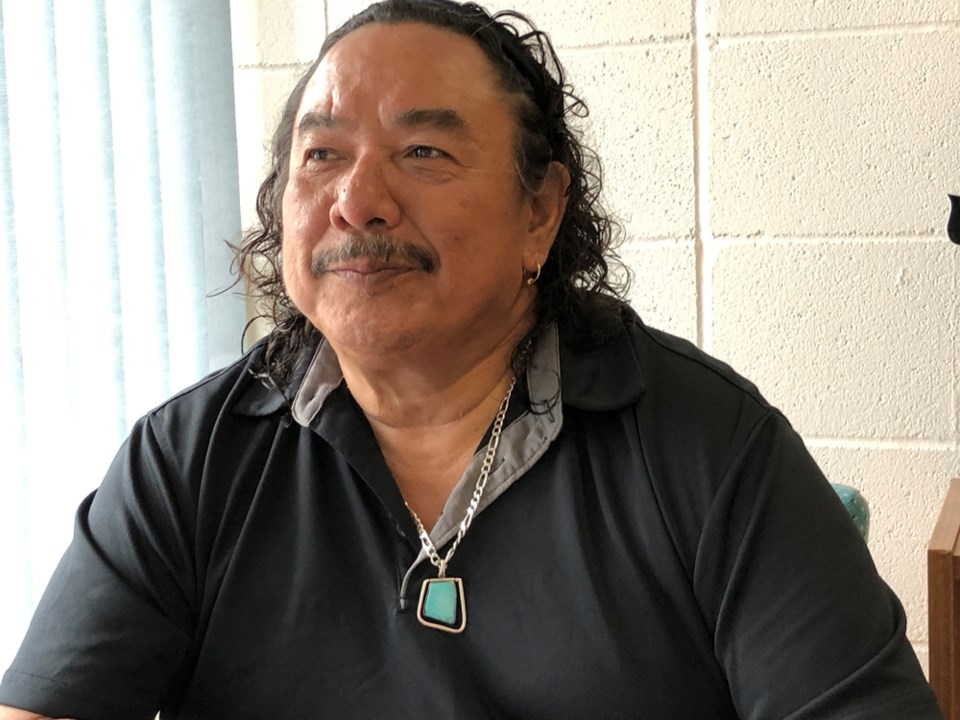

Omeassoo, who is Cree and originally from Samson Cree Nation in Maskwacis Alberta, was sent to Ermineskin Indian Residential School when he was five years old.

One of the largest residential schools in Canada, the Roman Catholic-run institution operated in Alberta between 1895 and 1975. The Ermineskin Cree Nation later took over the school.

Omeassoo said he thinks about his own three boys and how different their experience as children was from his own.

“I watched them and babied them and made sure they stayed in the yard, made sure they didn’t hurt themselves. When I was five years old, I was marching off to a residential school....This guy in a long robe, him and this other person drove me off,” he said, adding he recalls his grandmother quickly packing him a plastic bag full of belongings to take.

He was at the school for three years and suffered the horrors that are becoming all too familiar.

“There were abuses that were happening, and to this day I am traumatized by the way other people were treated,” he said. “You get used to children being assaulted, and you learn to stay in line and keep walking and don’t look — terrified that it will happen to you.”

He said he was also abused at the school.

His hair was cut and he wasn’t allowed to speak his language, even though he didn’t speak English when he was sent there.

“I knew right away from the older boys and from my cousins who were there, ‘Don’t speak Cree or you will be punished,’” he recalled.

“I was terrified to be there, so I did everything not to talk. Not to even say anything.”

Today, Omeassoo is a mental health worker with Vancouver Coastal Health and a popular amateur chef with a cooking series coming out on APTN.

He previously won an Aboriginal Cook-Off on the channel.

Horrific confirmations

With each new announcement confirming the bodies of children found on the grounds of residential schools, Omeassoo weeps for days.

He knows it could have been him, he said.

He thinks about the remarkable life he has lived and the lost potential of the many who died.

“I kept reliving those first three years, and those feelings were coming up and how it felt,” he said, of his reaction when the 215 children were found in Kamloops, confirming what local Indigenous folks had long believed had happened there. “I was talking to friends, and my sons were calling me on a daily basis, and I had good people around me. And then it is another one — 750 in Saskatchewan and then I started over again and got upset again.... It is not going to stop.”

Loss of culture

Omeassoo said he became disconnected from his culture after it was stripped from him in residential school.

Later, when he was in high school — where he was the only Indigenous student — he earned popularity through sports and played down his Indigenous heritage.

He was able to fit in, but not for long. When other Indigenous students arrived, his popular status changed.

“Native kids from northern Alberta came to finish their schooling,” he recalled.

Those kids were not accepted and faced racism, which rubbed off on Omeassoo.

“The whole school put eyes on them and, as a result, put eyes on me because I had brown skin too, and I was one of them. That ruined my whole life, and so I was very angry at those Natives for coming to my school.”

After that he moved even further away from his Indigenous identity.

He later involved his three sons in powwows and other Indigenous traditions, but wasn’t enmeshed in his Cree Nation culture and didn’t talk about residential school.

“I think I was in denial about my Indianness for quite a few years,” he said. “Now, if I ever had a grandson or granddaughter, I would show her everything. I would buy her regalia and take her to powwows and stuff like that. I am a lot more open to the idea of my nativeness and sharing it — advertising it.”

When one of his sons was seven years old, the boy found a medicine pipe in Omeasoo’s closet and asked about it. It had been Omeasoo’s late grandfather’s.

“He said, ‘Show me!’ and I said, ‘I can’t show you. I don’t know how to do this stuff. But I tell you what, I am going to find out,” Omeasoo recalled.

Omeasoo later went to Alberta and learned all he could and shares as much as he can these days.

He was given the name “Awasis,” meaning eagle child, in a ceremony.

He is known as a knowledge keeper now.

Room for faith?

Omeasoo said that while everything about the residential school was horrible, he hopes folks who need it aren’t abandoning their faith because of it.

“If you believe in something, continue with that,” he said. “Those people were evil. They were pedophiles and abusers.... [But] I don’t want people to say ‘Oh, I don’t want to be Roman Catholic.’ I don’t think that is the story."

What can non-Indigenous people do now?

Omeasoo said when he brings up residential schools some non-Indigenous people put their heads down and go quiet.

“I know you don’t understand, but I want you to not pretend it didn’t happen, either. It happened."

He said this is not ancient history and shouldn’t be treated as such.

“We are never going get over it. It will always be there. I want Canadians to know that it is always going to be there. It is a dark chapter of Canadian history for sure. Don’t ignore it.”

He said most of all, non-Indigenous people can speak up.

“I think it is your responsibility to educate other white people... If they are talking negatively about it or saying ‘Those Natives should forget about it,’... take a little courage in your heart and say, ‘That is not right. We should acknowledge that.’ Educate others. It is important as allies that they help us. Not just sit quietly. If you don’t say something, you become part of the problem of burying it.”

Canada Day

Omeasoo stressed that he is a “proud Canadian,” and has two nephews serving in the Canadian military.

“Not to cancel all Canada Days, but I think it should be cancelled today. I am proud to be Canadian, but I am acknowledging this is happening, too. It is not a time for me to go out and celebrate my Canadianness.”

He said he hopes this Canada Day is spent mourning and reflecting.

“If you have a party and somebody passes away, you stop the party, and we grieve and have an opportunity to heal and to pray and move forward. We don’t just go throw a party anyway. I think that is the way it should be today,” he said. “It is not ‘Happy Canada Day.’ It is not. It is ‘Sad Canada Day.’ That is what it is.”

Approximately 150,000 First Nations, Métis, and Inuit children were removed from their families and taken to residential schools in Canada.

(Another former Ermineskin Indian Residential School student shares his story on the Indian Residential School History & Dialogue Centre site.)

The Indian Residential School crisis line is available for residential school survivors and their families 24/7 at 1-866-925-4419.