There’s 384,000 kilometres between West Vancouver and the moon – but that doesn’t mean it can’t feel like home.

This summer, four West Vancouver student scientists were part of an international coalition tasked with converting a twilit wasteland of silicon, magnesium, iron, calcium, and aluminum crust into a bustling resort town on the dark side of the moon.

It’s a “mega city,” explains Hannah McDonald, a Sentinel Secondary student entering Grade 12.

The idea, McDonald continues, is for the settlement to be the moon’s second city; a buzzing metropolis attracting not only Earth-dwellers, “but also people from the other [lunar] city to come and visit.”

The experiment was part of the International Space Settle Design Competition, an annual NASA event that allows tomorrow’s scientists and engineers to grapple with the problems vexing today’s engineers and scientists.

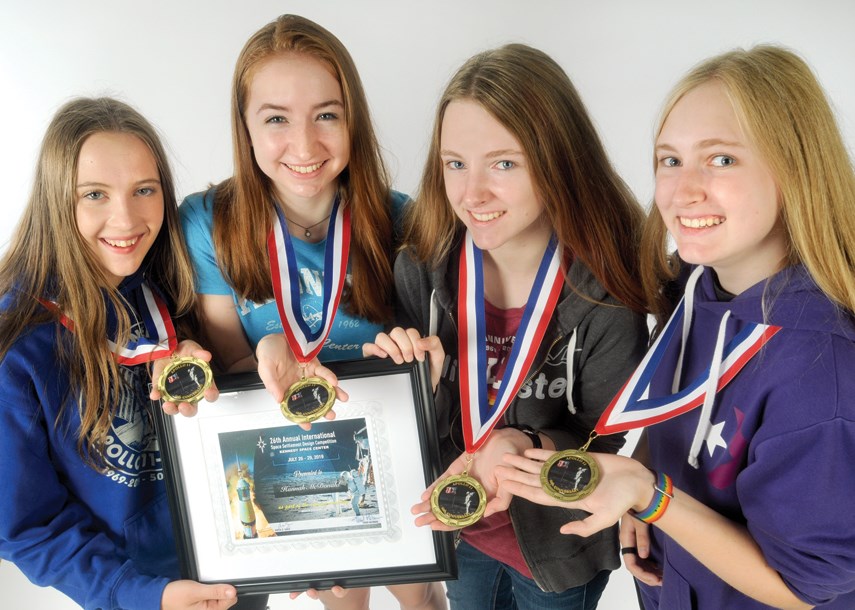

Over 42 hours at the Kennedy Space Center in Florida, West Vancouver students McDonald, Gabrielle Huchet, and sisters Lauren and Megan Spee worked alongside teen scientists from India, Uruguay, the United States and England as part of a 60-person aerospace corporation. On their way to a first-place finish, the team designed a 16,000-person colony while figuring out what people would eat, where they’d get toilet paper, and what they’d see when they looked out the window.

Before finding themselves in that high-pressure, high IQ atmosphere, each of the teens reported a scientific curiosity that surfaced in childhood.

Huchet, a Sentinel Secondary student now pursuing chemical engineering, recalls mixing mud-and-stick concoctions as a kid and observing reactions.

“I think I just like the possibilities,” she says of chemical engineering. “You could really do anything.”

Similarly, McDonald remembers combining every variety of shampoo in her parent’s bathroom as she sought to make the ultimate hair product. Today, she’s pursuing engineering.

“Engineering is a real way you can impact the world,” she says.

Now attending Rockridge Secondary, the Spee sisters grew up with an interest in space and rockets.

“We come from a family of engineers,” Lauren says, listing both chemical and civil engineers in the family tree.

“I’ve always been interested in space,” Megan notes, describing a recent model rocket launch.

She’s a regular watcher of SpaceX launches but it wasn’t until this summer’s design competition that she began to see her passion as a “very possible” career.

It was a rare opportunity, McDonald agrees.

“At school, you’re not going to have the opportunity to work with 20 or 60 people, especially people from all around the world.”

There was a chance to network, get simulated engineering experience and to meet a broad array of people who all shared a very specific interest, Megan adds.

Following a tip from Rockridge woodshop teacher Mr. Henning, the four friends competed in the Canadian semi-finals in May before being invited to join the national team in July.

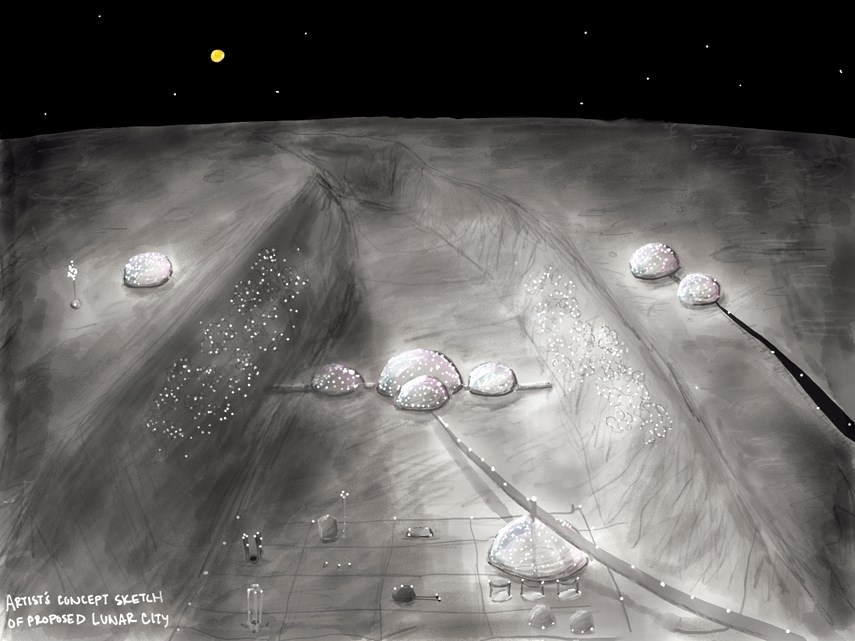

Following their arrival in Florida, they were given the assignment of taking the strangeness out of a strange land. In the year 2059 – in the interest of establishing settlements in space – their 60-person aerospace corporation was asked to design an urban village with a population of 16,000 on Pink Floyd’s preferred side of the moon. And, in a 35-minute presentation and a 50-page summary, the team had to demonstrate their design, define areas, justify building sizes and infrastructure locations while explaining how each element of the city would be built, how long construction would take and how much it would cost.

“It’s not super-specific,” Lauren acknowledges.

Huchet agrees.

“They gave us hints as to what they want, but really, it is up to us.”

The team was divided into marketing, structural engineering, operations engineering, human engineering and automation departments. With several languages spoken in every department, communication was crucial, McDonald says, describing discussions that were part-charades.

Megan was tasked with drawing maps, communicating with the entire company and updating her maps accordingly.

Because the city was situated in a shallow canyon, the team decided on dome-like structures and then added industrial roads, antennae, and slowly built the city while trying to keep a grasp on both physical and psychological needs.

“We actually went around and asked everyone in the company: what would you miss from Earth?” McDonald recalls. “Everyone agreed nature was one of the big things; being able to walk outside into a park.”

They needed to account for the physical toll of one-sixth gravity as well as the emotional toll of not being able to see the Earth.

They added greenery, windows, lighting and slowly, the settlement evolved.

“We really wanted to capture a big city feel that you would have on Earth,” Huchet says.

But through it all, there was dust.

On the moon, the dust kicks up like gunpowder billowing out of a musket. It coats, corrodes, irritates, and interferes. It may have hastened the demise of a rover. NASA astronaut Harrison Schmitt – the last man to walk on the moon – was allergic to it.

In Florida, those corrosive clouds were left to Lauren and the operations team.

The city had a mass driver to receive cargo. Exactly how the electromagnetic catapult worked “was automation’s problem,” Lauren explains. But getting supplies from the mass driver to the city was Lauren’s problem.

She helped design a system in which automated trucks would carry supplies down the long road to the settlement, removing casks onto indoor vehicles that could complete the delivery while hopefully nor tracking in any lunar dust.

“I don’t think even they had a solution,” Lauren says of the NASA engineers.

The last night of the competition saw the team pull an all-nighter to fine tune their presentation.

Huchet recalls sleeping for three hours and then waking up and to find everything was changed.

“A ton of moving pieces,” she says.

Ultimately, the team’s presentation was good enough to win the contest.

After returning home and preparing for the school year to begin, all four said they could imagine living in the city they helped design.

“It was educational,” Megan says – although she’s not certain she’d like to do it for living.

“I’ll go back to building rockets,” she says.

“It really taught me a lesson about how communication is essential,” McDonald says.

Huchet agrees, calling the experience an: “incredible opportunity to collaborate with so many different perspectives and minds.”

More than aerospace engineering, she learned how to work with one collective mind.

“I’d definitely like to do it next year,” Megan says. Her friends nod in agreement.

The moon is still 384,000 kilometres away. But for four friends, it’s a little closer than it used to be.