Looking at Persepolis: The Camera in Iran, 1850 – 1930, The Polygon Gallery. Until Jan. 13. For details visit thepolygon.ca.

In the same way U.S. presidents have seized on the power of television and Twitter, Iran’s ruler saw the implications of the finest tech the 19th century had to offer: the camera.

In 1842, the Czar of Russia sent an early daguerreotype camera to Iran as a gift. It was an ocean of time before the nice bright colours of Kodachrome, before anyone shook it like a Polaroid picture, and before it was strange to see a head of state on Instagram. It was still 18 years before Mathew Brady immortalized Abraham Lincoln.

But even before all that, Naser al-Din Shah saw the device’s potential.

The Polygon Gallery is currently showing Looking at Persepolis. Curated by Pantea Haghighi, the display examines 80 years of photos around the ancient city as well as insight into “how the medium was used as a propaganda tool to benefit an ailing dynasty,” she explains.

“This exhibition looks at 80 years of looking at Persepolis. That’s where the title comes from.”

The rulers of the Qajar Dynasty were descendants of the Ottoman Empire, Haghighi points. That lineage cast them as outsiders even inside the empire they ruled.

“This was a Persian Empire so the Qajar wanted to affiliate themselves with the best of the best of Persia,” Haghighi explains.

For Naser al-Din Shah, the best of Persia was to be found in Persepolis. Named for a Zoroastrian prophet-king, the city was designed to serve as the capital of the Achaemenid Empire.

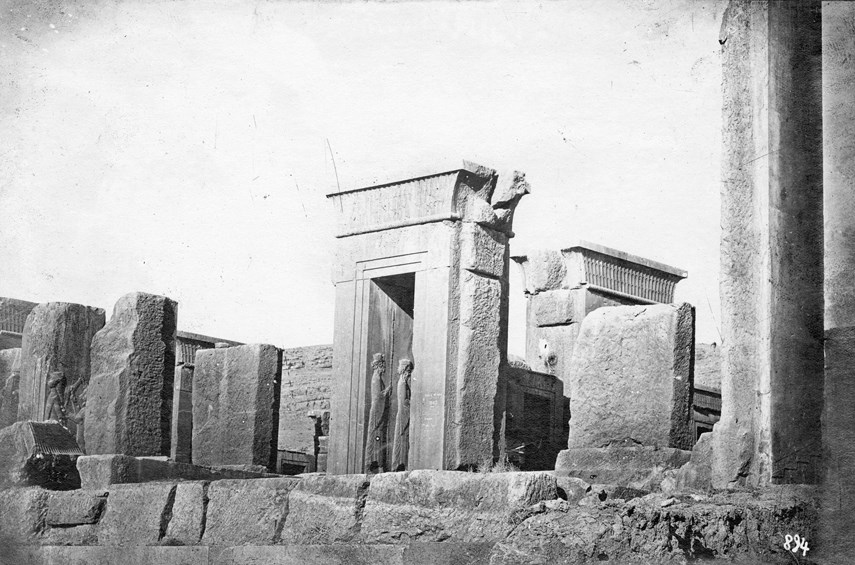

Strolling through the exhibit, Haghighi notes the ruins that stick out from the soil like stumps. But decades of archeological exhibitions later, the dirt is gone and the pillars tower once again.

Because of geographical challenges posed by nearby mountains, as well as the burning and looting led by Alexander the Great, the city was eventually abandoned.

But in the second half of the 19th century, an era characterized by major wars and a “nearly bankrupt government,” Naser al-Din Shah tried to build a national identity around what Persepolis represented. That representation would include him, of course. And in order to draw a line from the “glorious past of ancient Persia” to his own rule, he chose photography.

“In Iran, the camera was both an archaeological and ideological tool,” Haghighi notes.

During the mid-19th century French, Italian and German archeological teams came to Iran. Often, they would leave a photographer behind who would work for the king, Haghighi explains.

In turn, the king would send them 40 miles northeast of Shiraz to Persepolis.

Some of the exhibition’s earliest photographs are taken by Luigi Pesce, who documents the ruins of Persepolis in tight shots subsequently developed on salt paper brushed with silver nitrate.

By the 1880s Pesce’s tight shots gave way to panoramic views that document the ruin of Persepolis along with the glory.

The evolution in craft is likely hastened by the money the king poured into photography, Haghighi says. Photography replaced painting in the king’s court, she notes, gesturing to a portrait of Naser al-Din Shah on the wall.

The paintings of Naser al-Din Shah were complemented by photos of the ruler looking stately and powerful at his best and like an exhausted Groucho Marx impressionist at his worst.

“It was a sign of prestige for him,” Haghighi explains of the photos.

While other kings celebrated moments leading troops on horseback or killing a menacing animal, al-Din Shah’s “victory moment was being photographed,” she says.

Walking through the Polygon Gallery, Haghighi is quick to delve into the history behind every photo. The 80 pictures on the walls are the net result of sifting through thousands of images, she says, gesturing to a collection of photos sent from Iran to the Vatican in an attempt to secure funding for further archaeological expeditions.

“it’s interesting what angles they’re trying to show . . . to sell Persepolis to the Vatican,” she says, noting the Greek images in the album.

Overall, the photos are distinct from the documents that survive from the same era in Egypt, Haghighi says. The photos of Egypt tend to linger in harems in an attempt to chronicle the exotic and objectify women, she says.

But the photos of Iran are more true to the country.

“It’s not being orientalised,” she says. “That’s what sets Iran apart: it was never colonized.”