Like all of us, she contained multitudes.

It was 1983 and Michael Kluckner, history writer, artist and president of the Vancouver Historical Society, was busy researching for his latest book, Vancouver: The Way It Was, when he first encountered Julia Henshaw.

“I was looking for interesting characters that I could write short biographies on, the sort of thing that would sit in the margin of a big book that was concerned with larger heritage,” Kluckner tells the North Shore News.

He came across a reference to a man named Charles Henshaw, nicknamed “Afternoon Tea Charlie” for his merrymaking sensibilities and general joie de vivre, who had infamously imported Parisian bathing suits for a celebratory soiree only for partygoers to soon discover that the suits “disintegrated in water,” according to Kluckner, who notes: “What a scandal that would have been!”

“You think of how buttoned down the society was in 1910 – I thought this guy seemed like a really interesting character and so I went looking for him, and couldn’t really find anything at all,” says Kluckner. “But there were numerous references to his wife Julia, who seemed to be an entirely different, very serious, very motivated, driven, quite modern woman.”

For the last 30-plus years, Kluckner slowly chipped away researching Julia Henshaw’s life. He combed through old newspaper clippings, scanned records where he could find them, and pored over primary source materials from books that Henshaw had penned herself.

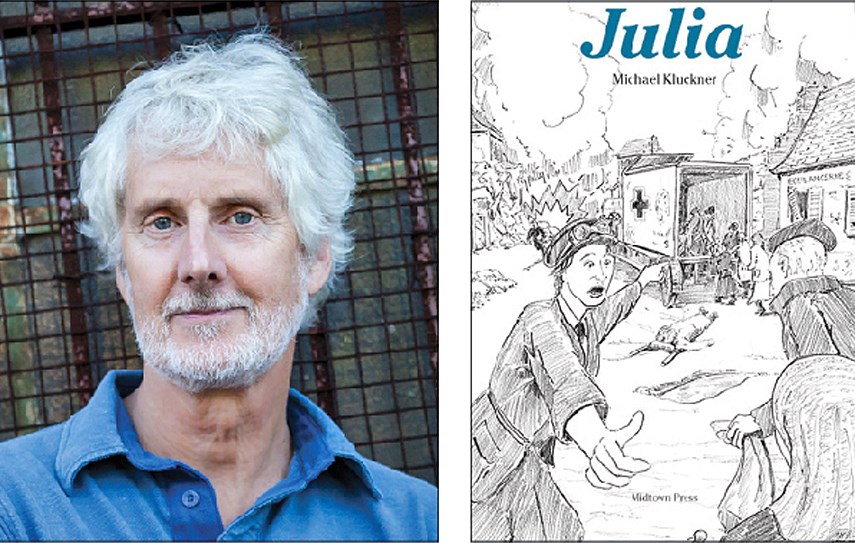

His collected findings are presented in the biographical graphic novel, Julia, which came out last year. Last week, he gave a lecture on the life and adventures of Henshaw to a packed room during the West Vancouver Historical Society’s March meeting.

A noted author, lecturer, botanist, explorer, socialite, and wartime volunteer, Henshaw and her husband established their home in West Vancouver’s Caulfeild neighbourhood in the early 1910s, making them among “the very early purchasers of land out in Caulfeild,” according to Kluckner.

“And Caulfeild itself is kind of a quirky community – the little winding roads, and Piccadilly is the name of a road out there. It’s very picturesque,” he says.

Asked what Kluckner found so interesting about Henshaw when it came to the early annals of Vancouver history, he says her proficiency in writing, exploring, journalism, botany, as well as her overall “high-powered public persona,” made her an excellent example of a person living here 120 years ago who had broad interests and a general air of sophistication. Her garden on Piccadilly North, for example, was well known in the 1920s and ’30s, and was said to be one of the first on the West Coast to feature alpine plants, likely harvested during one of her many outdoor excursions.

Perhaps her greatest feat, explains Kluckner, was volunteering abroad during the First World War, where she was awarded the Croix de Guerre for her bravery in helping to evacuate people under shell fire and aerial bombardment.

She wasn’t without her faults, too. Many of her viewpoints regarding women’s suffrage and imperialism would be considered regressive or racist today, explains Kluckner.

It’s a notion he wrestled with while writing the graphic novel – a form he likens to doing “poor man’s filmmaking; effectively they’re elaborate storyboards” – but reasoned he didn’t want to insert his 21st century judgments into the story of what was ultimately a fascinating and complex woman, full of dichotomies.

“On one hand she was making a living as a woman, she was writing under her own name when she was still in her 20s as opposed to writing under her husband’s name or that type of thing. But then, the weirdness of it with her being anti-suffrage – she goes against the major trend in Canadian women’s history at that period of women wanting to vote,” says Kluckner.

He even inserted himself into the narrative as a character who interacts with Henshaw’s ghost in order to address these issues.

“As her ghost says at the end: ‘Your society is just a bunch of hypocrites.’ You push all this stuff out of sight in a way that couldn’t happen in her day – getting clothes made in Bangladesh, getting your food grown by Mexican labourers and trucked up here,” muses Kluckner. “She is just so complex.”

Visit Michael Kluckner's website for more information about the book, michaelkluckner.com.