Long grass covers low banks surrounding a swimming hole with blue-green water.

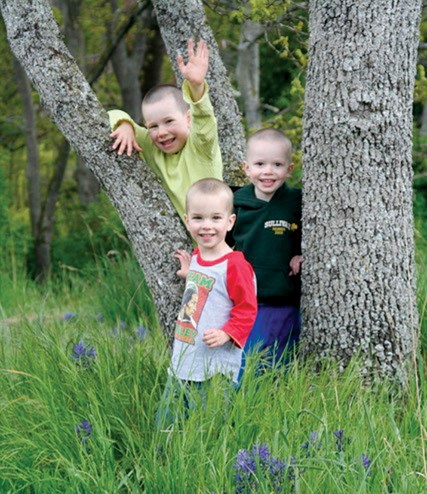

Three young siblings splash about, laughing, frozen in time. It’s a serene scene depicted in this photo taken more than 10 years ago on a family camping trip in Montreal. Sarah was three at the time and the twins, Baird and Finn, were just one year old.

The enlarged snapshot takes centre stage on a wall full of pictures in the kitchen of the Sullivan family home in North Vancouver. Patrick Sullivan recalls talking about this photo of his kids during a recent presentation he was giving at a pediatric cancer research event in California.

“That was really hard for me to talk about; how we don’t get that, we can never have that anymore,” he says, recalling the family trip to a private fishing camp. “It hits you at surprising times and still does. The sudden shock of cold water: there’s something fundamental missing here.”

Finn Sullivan was born one minute after his twin brother Baird in June 2005. Just four months shy of his second birthday, Finn was diagnosed with a rare form of childhood cancer called rhabdomyosarcoma. It is a type of cancer that involves skeletal muscle and attacks various parts of the body.

The discovery of a grapefruit-sized tumour marked the beginning of a long journey for Finn, which involved more than a year of chemotherapy, radiation, and surgery. After Finn completed the treatment protocol, doctors told his parents there was no evidence of the disease. But as Patrick and his wife Samantha explain, that didn’t mean he was in remission. Instead, it became a wait-and-see scenario.

Detecting microscopic cancer cells in hiding was a difficult task then and still is now. Ultrasounds, MRIs, even blood tests can’t always catch a recurrence. Sifting through millions of healthy cells to find the small cluster or lone wolf that might indicate the cancer is clawing its way back is just beyond medical science in many cases.

“They didn’t detect anything when they stopped treatment but it was still there,” notes Samantha.

The cancer came back and it spread. Quickly. On Oct. 9, 2008, Finn Sullivan died. He was three years old.

“He was a boy who loved life and lived like he loved it,” Patrick says of his son. After a long pause, he adds: “It’s verboten to say he lost his battle because Finn didn’t lose. He died. Battles are about how you live not why you die.”

Not long after their son died, Patrick and Samantha started a fundraising charity aptly named Team Finn. Over the years, Team Finn members and supporters have participated in and created a variety of events to raise money for pediatric cancer research.

But in the nine years since the initiative began, the couple’s role has expanded and evolved from local fundraising to include national and international advocacy.

“We were not thinking bigger at the time,” says Patrick of the initial Team Finn concept. “It was a way to just do something in an area where you’re helpless.”

In the beginning it was all about their son, adds Samantha. “We had a lot of support from the community while he was sick, and then that just kind of morphed into continuing a celebration of him and raising money to remember him and honour him and help other kids.”

As more money was raised each year, though, the couple felt a responsibility to know how it was being used and decided they could be a voice in guiding where it was going. While fundraising was the initial focus, advocacy opportunities evolved over time.

As part of that advocacy, every month this year Patrick has travelled to a different city in support of the pediatric cancer cause. (Patrick’s advocacy work is volunteer and his travel and accommodation is covered by sponsors or the family’s personal funds, not Team Finn.) He is regularly involved in making presentations to groups and stakeholders (including doctors and researchers), helping to apply for grants, and serving on scientific advisory boards for clinical trials and new therapy projects.

“None of this was planned,” he admits, but adds it’s necessary because fundraising and advocacy complement each other. “They’re all really important, differently important. The types of innovative, groundbreaking scientific projects I’m involved in as an advocate can’t happen without the fundraising that happens at the grassroots level.”

It can take 10 to 15 years before the science around an idea grows to where it reaches patients, explains Patrick. The process is long. And there is still much work to be done.

When Finn was first diagnosed in 2007, his parents were told he had a 70 per cent chance of surviving. That number refers to the five-year survival rate, but Patrick says patients aren't well tracked after that.

“If we met with those same doctors today, and with the same diagnosis, we would be told 70 per cent. If we had met with those doctors in 1997 we would have been told 70 per cent. If we met with those doctors in 1987 we would have been told 70 per cent,” says Patrick.

The numbers haven’t budged in more than 30 years. And while 70 per cent may sound like pretty good odds, consider it from a different angle: three kids out of every 10 diagnosed with Finn’s type of cancer will die.

“The treatment failed him,” Patrick states firmly. “Sometimes you’ll hear that someone failed cancer treatment. No, the cancer treatment failed Finn.”

The Sullivans believe that research is the way to change the story for another child, and there are a number of clinical trials bubbling with possibility, getting close to the surface for patients with rhabdomyosarcoma.

“We’re in a golden age of cancer research. We’re in a place where money invested now can make a huge difference in the next five to seven years,” says Patrick. Targeted therapy and personalized medicine, thanks to gene mapping, are the latest part of the game plan. “If Finn was newly diagnosed he would probably be going through the same treatment, but at the time of (his) relapse there was nothing, no clinical trials, nothing available. That’s different now.”

In June, the Sullivan family celebrated a milestone: Baird turned 12. There are now two teens in the house as Sarah is 15. The siblings don’t remember much about the time their brother was sick. They were too young. But Sarah says staying connected and talking as a family has helped her process the experience. Baird likes to listen to audio books as a way to decompress. Rick Riordan’s Percy Jackson & the Olympians series is among his favourites. They both play sports and Sarah is an avid music fan.

“She likes any kind of music from musicals to punk rock, Johnny Cash to the Clash, to Les Miserables,” her dad reports.

Not surprisingly, the teens don’t have much to say to the inquisitive reporter in their kitchen, but they are polite and even answer a question that would make many kids cringe: Tell me something unique about your sibling.

“When he gets interested in a topic he gets really into it and likes to talk about it,” says Sarah of Baird.

With a little prompting from his mom to “say something nice,” Baird offers this about Sarah: “I like talking to her, having conversations. She’s a good sister.”

Once the kids are freed from the interview and allowed to resume lounging about in true summer-vacation fashion, Samantha notes that they are both reflective in nature, more so now in adolescence.

She enjoys this stage of parenting, describing it as “interesting and fun.”

But each year as they celebrate Baird’s birthday, it is impossible to ignore the fact that his twin is not with them. It’s a sensitive area to navigate, the parents admit.

“For us as parents the twin element was an element of loss as well, and for Baird because they were so close,” says Samantha.

The first night the brothers ever spent apart was the night Patrick and Samantha took Finn to the emergency department at B.C. Children’s Hospital when he first started showing symptoms. One component of the couple’s pain during Finn’s illness was realizing more than Baird did what he was going to lose.

And while they continue to honour both boys each year, the family also sets aside a special day for each one. Baird’s on his birthday and Finn’s on Finn Day, which they celebrate on the day he died.

On Finn Day the family gathers with friends, shares memories, and writes messages on a balloon they release into the sky for the little boy they lost. They also do an activity that has a special connection to Finn, such as go-carting (he liked fast cars) or taking a trip.

“It gives us an opportunity to tell (Sarah and Baird) more stories about Finn and what he liked and some things they did together because they don’t have those memories,” says Samantha.

Despite the absence of specific memories, their brother’s death was unquestionably a formative experience for both Baird and Sarah, notes Patrick.

“The time they walked up the driveway holding hands, or when they opened that window and almost fell out into the snow, or when Sarah sat with us at Canuck Place listening to music with Finn in the last week of his life, they don’t have those specific memories like we have. But having a brother die at the age that he died and having parents grieving after that, there’s no question that’s formative,” he adds.

Coping as parents after Finn died was made easier by the fact that the couple didn’t have an option to crumble.

“How do you cope when you’re grieving, your child has just died, you’ve got this huge gap, but you still have a three-year-old and a six-year-old? You cope because you have to,” says Patrick.

Not having a choice to fall apart made the process of recovery both extremely hard and extremely easy at the same time, says Samantha. “Extremely hard emotionally and extremely easy because that’s just what you have to do.”

The Sullivan family’s story is familiar to many in their North Vancouver community who have been following their ongoing fundraising efforts.

And the pink jerseys they wear as part of Team Finn’s participation in the annual Ride to Conquer Cancer are a familiar sight about town. The jerseys are pink because Finn was partial to the bright colour, a preference sparked by the plush pink bear he carried with him during treatments.

On the right shoulder of Team Finn jerseys is a peregrine falcon that carries a double meaning. Peregrine falcons are renowned for their speed and Finn loved speed. Saint Peregrine is also the patron saint of cancer patients.

Next year will mark another important milestone for the Sullivans: it will be a decade since Finn died.

Overall, the family is doing well these days but Samantha admits it has been a hard road: “It’s been a long period of adapting to a new life, a new existence.”

Patrick adds: “This false notion of getting over it is bullshit. That doesn’t exist. You get on with it, and finding your bearings and what that means takes a long time, and it’s never done.”

He points to the left shoulder of the Team Finn jersey he is wearing. It features a string of 33 beads. Traditionally, each time a child with cancer completes a treatment they are given a bead to add to a string they wear in hospital as a badge of honour and courage. Although Finn earned hundreds of beads in his short life, the 33 beads on the jerseys are a tribute to a friend who also died of cancer.

Every year, one bead is removed from the jersey to represent the contribution Team Finn has made to the cause and the lasting change their efforts are working to bring about for kids with cancer. When all the beads are gone, the Sullivans say their work will stop. And while their efforts are admirable, their journey to help find a cure has been a long one with many miles to go. Do they still have hope of one day reaching that golden goal?

“Yep,” Patrick answers quietly. “Yes. Legitimate hope. Wouldn’t continue doing it if I didn’t have that legitimate hope.”

• • •

The annual Ride to Conquer Cancer takes place Aug. 26-27. Visit teamfinn.com to learn more or to donate.

An annual event called Ben’s Big Lemonade and Bake Sale for Team Finn takes place Sunday, 1-4 p.m., at 1960 Rufus Dr., North Vancouver. New this year: everyone visiting the sale will get the chance to contribute to a custom paint-by-numbers painting of Finn.