West Vancouver resident Anand Jain was stunned when he got his property assessment notice this year.

The value of his home at 2035 Westhill Dr., just above Highway 1 in the British Properties, jumped 52 per cent this year – from $2.86 million last year to $4.35 million this year.

“It’s a big surprise to me,” said Jain. “I called them lunatics.”

Jain, who is retired, said he can’t understand how a house he bought 24 years ago for $820,000 could have ballooned so much in assessed value.

He’s not alone.

As homeowners have discovered when they received assessment notices this month, property values are up. Way up.

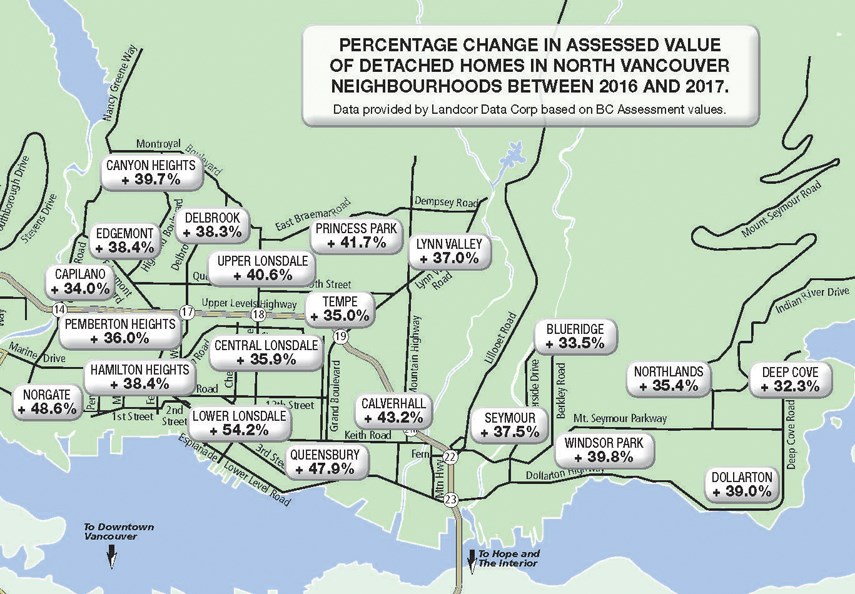

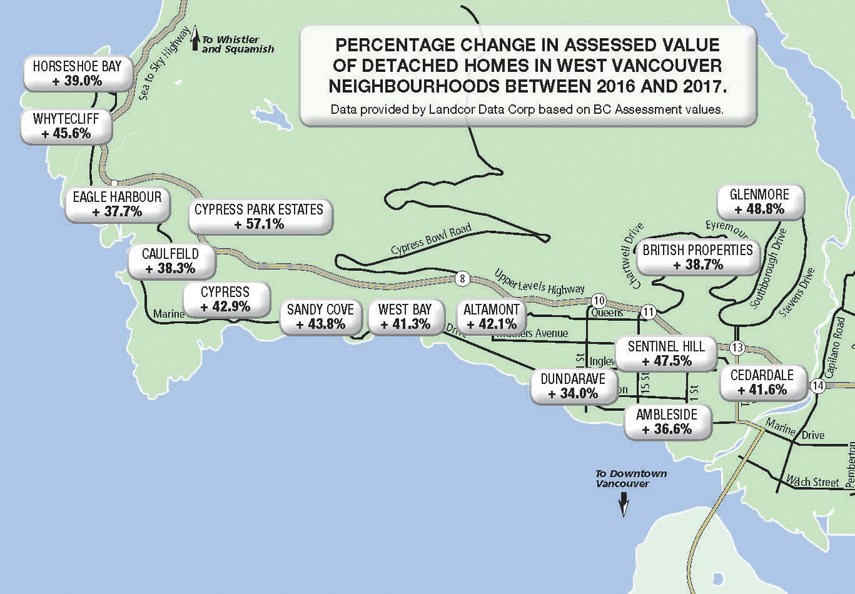

Average increases in residential assessments range from 33 per cent in the District of West Vancouver to 36 per cent in the District of North Vancouver. But those averages include all kinds of properties – including condominiums, townhouses, apartment buildings and vacant lots.

The assessment hikes for single-family houses – dwellings which still account for the majority of homes owned on the North Shore – have been even more dramatic.

In West Vancouver’s Cypress Park Estates neighbourhood, for instance, average assessments are up more than 57 per cent from last year, pushing average values among the 372 homes there to $3.7 million from $2.5 million last year.

Homes in the exclusive neighbourhoods of Sandy Cove, West Bay and Altamont are up between 41 and 44 per cent, bringing averages in the large properties of Altamont and West Bay waterfront to a whopping $6.4 million and $6.5 million. Houses in the City of North Vancouver’s Lower Lonsdale area are up more than 54 per cent to an average of $1.6 million. Canyon Heights and Edgemont neighbourhoods, which have seen plenty of teardown action and redevelopment, are up 38 to 40 per cent to averages of $2.1 million and $2.4 million respectively. Even homes in traditionally modest areas like Norgate and Lynnmour have seen average assessments of more than $1.3 million this year.

It’s a massive jump, more in a single year than most people in the real estate and appraisal sectors can recall in at least three decades.

Mayor questioning own home assessment

District of North Vancouver Mayor Richard Walton, who’s received about 20 calls and emails about the assessments from constituents, said he even found himself questioning how the assessment for his own home was arrived at.

“We’ve never seen a situation like this,” he said.

David Sheffield, who lives on Burley Drive in West Vancouver in a 61-year-old home, is also questioning his assessment.

Sheffield has lived in the home for more than 30 years and has largely kept it in its original state. “We haven’t done any big renos,” he said. There are no granite countertops or double-glazed windows. On the north side of Sentinel Hill, “traditionally it’s been one of the entry-level places for West Vancouver,” he said, on a bit of a busy street with some highway noise.

Yet his assessment is up 54 per cent this year – a value based largely on sales in the spring.

Sheffield said the way different properties are valued doesn’t always make sense to him. He points to two homes on his street on similar-sized lots – one, according to BC Assessment, a larger, well-maintained five-bedroom home of about 4,000 square feet, the other essentially a teardown. Yet the property with the larger house is only valued at $56,000 more than its ramshackle neighbour. “Nobody in their right mind would price those properties that close,” he said. Sheffield recalls one year he did some landscaping and got a notice from BC Assessment that his property value would increase because of his “renovations.” But Sheffield insisted he had done no renovations – he had simply taken down a hedge. “They extrapolated ...” he said.

Jason Grant, longtime area assessor for BC Assessment, said in setting a value on a property, the assessment office looks at the same things Realtors and appraisers look at – the size and condition of the house, size of the lot, whether there is a view or not, or if the property is on a main road.

“We maintain an extensive property database,” said Grant. “Keeping it up-to-date is a very important part of the work we do.”

The assessment office uses street-front images – such as those available through Google Street View – and high-quality aerial photography from municipalities, which can point to additions. Assessors also keep tabs on municipal building permits, rezoning regulations and official community plans and MLS listings, which can provide interior views.

Exactly how assessments are determined is a common question, said Grant. At its most basic, the assessment office first determines an overall value based on what other properties of a similar description in the area have recently sold for. Assessors then look at what vacant land is selling for to determine a comparative land value. Total value minus the land value equals a “residual” value assigned to the actual house, which is why the value of buildings can go up or down without any physical changes being made to them.

But the overall value of the two combined is what’s most important, said Grant.

Most people who question their assessments are able to resolve the issues informally, by speaking to an assessor.

Lynn Valley resident resolves assessment with assessor

Annette Wilson, who has lived in the same Lynn Valley home since 1981, was able to deal with her mind-boggling assessment increase of 168 per cent this way, which had landed her with a property value of $3.6 million.

Wilson has a big piece of property, over two-thirds of an acre, originally owned by her father. Back when she first lived there, in the early 1980s, many of the other homes in the neighbourhood were also on large lots, backing on to forest. But over the intervening years, things changed – new roads were built and most of her neighbours subdivided their lots. Wilson didn’t. She enjoyed her garden and the wildlife attracted to it. “It’s my sanctuary,” she said.

“I’m a single grandmother on a pension. I’m not a speculator. I want to live out my life here.”

In the fall, Wilson was informed by the assessment office that because her large property had increased substantially in value, she was eligible to apply for a special type of assessment relief.

The help, under section 19.8 of the Assessment Act, is granted to a very small number of homeowners – less than 200 of the 43,000 single-family homes on the North Shore, according to Grant – in cases where land values have soared because the property could be put to a substantially different “higher and better use” but the house is still being occupied by the owners as a regular home and has been for at least 10 years.

If all of those criteria aren’t met, the property won’t qualify for help.

North Vancouver family loses appeal

Last November, a North Vancouver family found that out the hard way after losing an appeal of the assessment for their residential rental property on Mountain Highway, which had jumped almost 361 per cent in one year to nearly $4.5 million – based on its potential to be included in a land assembly under its “highest and best use.”

In Wilson’s case, her large property has the potential for subdivision. Through talking to the assessor about the massive increase on her notice, she learned that the assessment “relief” had not yet been applied to her property. The database had also thrown in two extra bedrooms which don’t exist, based on assumptions from building permits taken out 25 years ago.

Within a couple of days, Wilson’s assessment was down – to a more modest 33 per cent increase, like everyone else’s in her neighbourhood. “I’m not going to argue about that,” she said.

For most people, the concern with higher assessments is the fear they will lead to higher property taxes, which is not always the case.

How much taxes go up or down is set by the municipality – and affected by how much your assessment has gone up compared to others in the areas. “Somebody could be really alarmed by a 30 per cent increase (in assessment),” said Walton. But if the average assessment hike is more than that, there’s a good chance that person’s taxes will actually be lower than in previous years.

“Yes, taxes can actually go down,” he said. “I know it’s not most people’s experience.”

Others don’t consider the impact of their assessment increases until their tax bill arrives in June. By then it’s too late to question their property value. Form letters stating an intention to appeal must be filed by Jan. 31.

Only between one and two per cent of homeowners do file appeals of their assessments with the property assessment review panel – the first step in the appeal process.

“I’ve talked to a number of people who appealed their assessments over the years,” said Walton. The message he gets back: “They need to do their own homework. It’s not a matter of standing in front of (the review panel) and saying ‘lower it.’ They have to go with some reasonably compelling evidence.”

Homeowners should check property info on website

Dan Jones, owner of appraisal service company Campbell & Pound, who sits on the board of directors for the Appraisal Institute of Canada, seconds that. The first thing homeowners should do is check online with BC Assessment’s website to make sure the information about their property is correct. Check sales the assessor has used to come up with a value. If they aren’t comparable, start building a case using different sales and properties that you think are similar.

Things that can change the value of a property include being on a busy street versus a quieter one, unusual right-of-ways or easements that restrict building envelopes, odd-shaped lots, nearby Hydro boxes and – if you’ve got a view property – even views that have been partially blocked by trees that aren’t on your property. Be aware, he said, that an appeal will often trigger an inspection, and “an assessor more than likely hasn’t been out to that property in 10 to 15 years.” So those renovations you did quietly five years ago that BC Assessment didn’t know about might suddenly show up on your assessed value.

While the assessment office strives for “equity” among similar properties, if your neighbour’s comparable property is valued lower than your own, it could be that person’s value which is off – not yours, warns Jones. “The assessor may be bound to increase (the neighbour’s) assessment, not lower yours,” he said. “It does not make you popular with neighbours.”

Sheffield said he’s appealed on a number of occasions, questioning the assessor’s comparisons to homes in more desirable neighbourhoods or which had views when his didn’t. In most cases he had some of his property value reduced. But that took work, he said – building a case in writing and including photos and examples.

The spike in his own assessment makes him worry about the impact on his tax bill. Over the last two years, a more modest rise resulted in a 40 per cent increase in taxes – partly because he lost the homeowners’ grant.

This year the timing of BC Assessment’s annual valuation – on July 1, near the peak of the market that has since fallen – has added to frustrations.

Yet having a common valuation date is the fairest way to divvy up who pays what in property taxes, said Grant. “In each and every year markets continue to move after our valuation date, either up or down,” he said.

Jones, who worked for the assessment office in the ’70s and ’80s, said it’s also a better system than the old one when each municipality did their own assessments, as well as collecting taxes.

Not many assessment appeals

Only one or two per cent of property owners appeal their assessments.

Jennifer Clay, who lives in a Grand Boulevard area heritage home that she bought 20 years ago, is one of them.

Since 1995, when she bought the house for $331,000, her property has more than quadrupled. Last year, when her property went up more than 20 per cent in value, Clay appealed, based on a comparison with a neighbour’s property.

Clay went before the property review panel and had the value of her home reduced. But that is not an easy process.

Like Sheffield, Clay spent hours researching comparable properties on the BC Assessment website and compiling a stack of photos and spreadsheets to argue her case. It was time-consuming and cumbersome, she said. She took time off work to appear at the 30-minute hearing. And there are no guarantees. “The people before me (in the hearing schedule) didn’t win,” she said.

Many people don’t.

Clay said she thinks it’s still worth it to appeal in cases where an owner feels their property has been unfairly valued.

“It’s kind of like voting,” she said. “If you don’t look at your assessment and compare to your neighbours’, you shouldn’t complain.

“People should take more interest in how they come up with the assessed value of their property,” she said. “It matters. It matters when it comes to paying taxes.”