The name escaped them.

As a rule, the District of North Vancouver council doesn’t get stumped. But in May 2015 they couldn’t remember much of anything about William Griffin.

Council knew everything about the rec centre that bore his name – except the reason it bore his name.

Griffin isn’t alone in his anonymity. If we know the streets and parks of North Vancouver we know the names Cates, Lonsdale, and Moody, but, as Butch said to Sundance: “Who are those guys?”

A boy named Sew and the North Shore’s fir traders

In reading the story of Sewell Prescott Moody we encounter a yarn spinning wheeler-dealer who visited Placerville, Calif., when they called it Hangtown.

However, that man is not Moody.

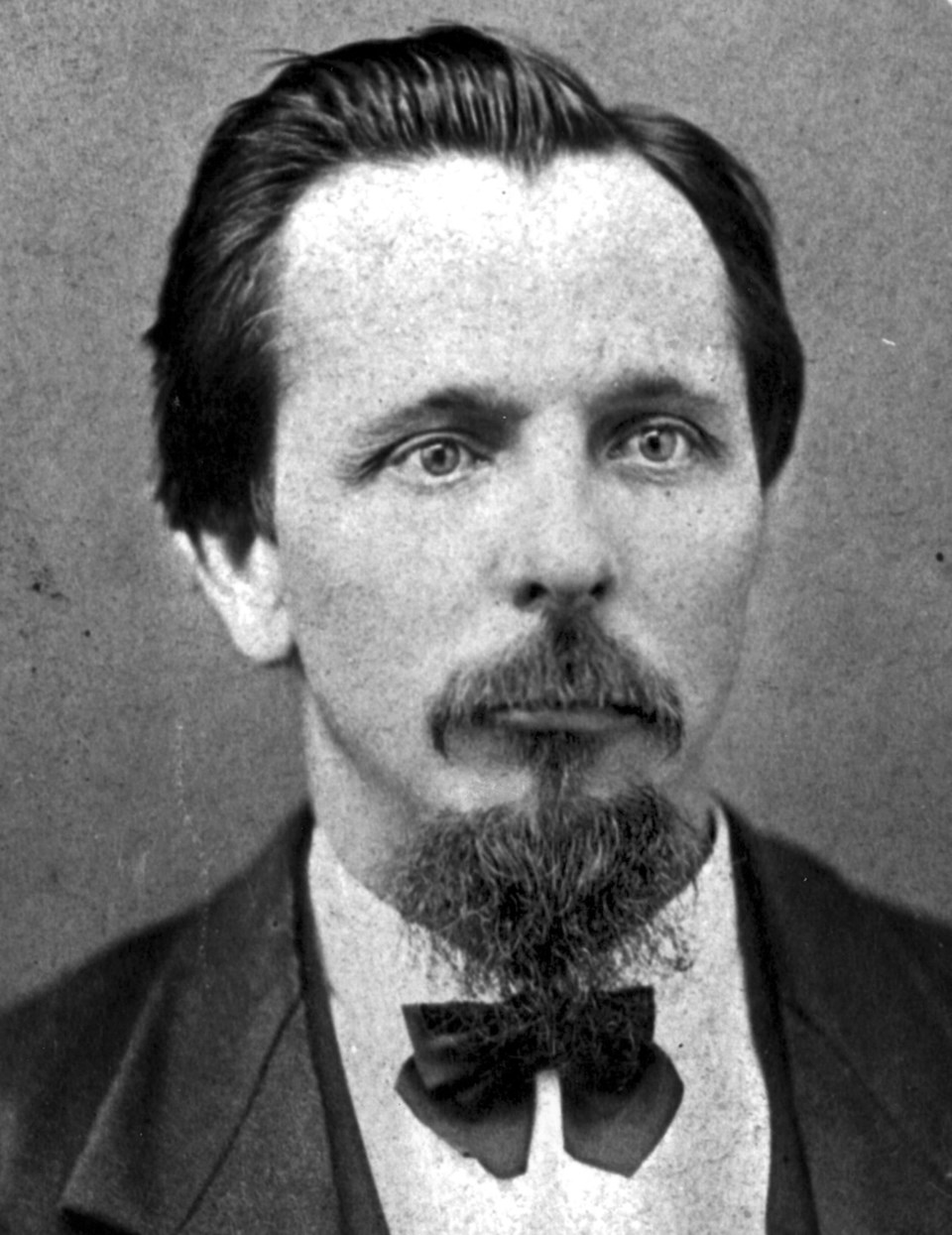

Sew Moody was closemouthed – whether under oath or not.

While business partner Moses Ireland wrote his life story in tall tales, the ambiguity of Moody’s background forces historians to use “such terms as ‘possibly’ or ‘probably,’” notes author James Morton.

There are photos of Moody but no evidence a smile ever contorted his Beelzebubian goatee or brought light to his melancholy eyes.

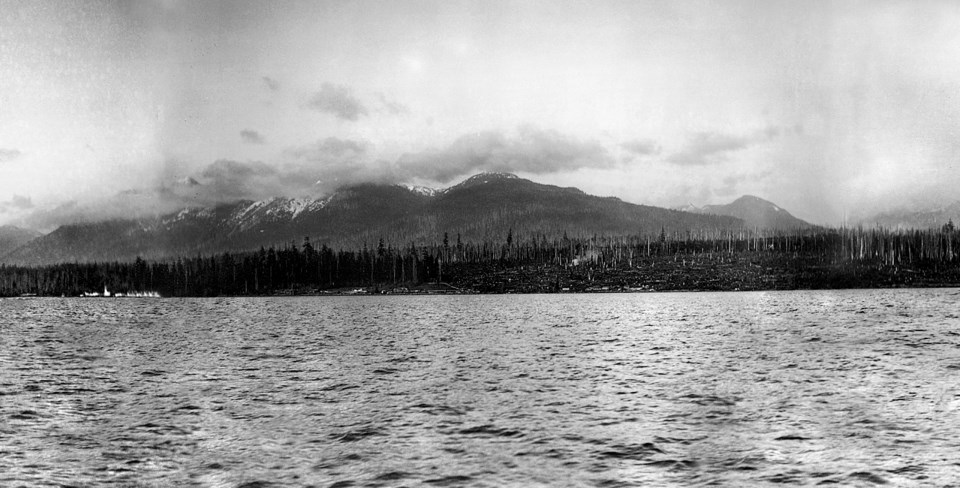

Moody was part of the wave of foreign buyers who transformed the North Shore in 1860, bringing woolen blankets, iron axes and smallpox, recounts historian Martin Wells.

North Vancouver’s waterfront had been bought for a penny an acre. And while the North Shore’s fir, cedar and spruce built New Westminster, Moody met Ireland.

Ireland was fresh off a profitable case of gold fever, pocketing $2,000 while prospecting in the Cariboo.

Despite Moody’s teetotaling tendencies, they may have met at the Pioneer Saloon, a tavern that marketed itself as a place for “drinking good whisky and indulging in an occasional weed.”

A partnership was struck, and after running steer from Oregon to New Westminster, they cast their eyes to the boom on the Burrard Inlet, eventually buying the mill and 480 acres for $6,900 in 1865.

Moody, who had offered $8,000 only two years earlier, “could never refuse a bargain,” Morton notes.

Running a timber mill required global connections. They had none.

So, with the optimism that sometimes colours terrible decisions, Moody shipped 290,000 feet of lumber to Australia and hoped for the best.

“The Captain had to sell or give the timber away and we got $400 for our two cargoes. … this spelled ruin for us,” Ireland recalls. “I went mining … and Mr. Moody stayed with the mill.”

Moody displayed a vulture-like genius for scavenging. The engine of a steam-powered gunboat powered the mill. When a schooner went down carrying piles of timber he bought it for a song, reclaiming both boat and lumber.

About 300 workers – sailors done with the sea, prospectors shaking off the dust and disappointment of life in them thar hills, Squamish Nation, Hawaiians, Chileans and Chinese workers – shipped 100,000 board feet every day to connections in Mexico and Australia.

The workers shared two commonalities: they needed the job and they had to get out of town when they needed a drink.

Moody banned the sale of alcohol. Wells describes the edict as a “benevolent gesture” meant to curb excess, but allows: “Moody was not universally liked for his temperance tendencies.”

Moody’s modest requests for more acreage included the phrase “shall ever pray,” and Morton posits he may have been related to a famed Evangelical preacher who founded Moody Church in Chicago, Ill.

In The Enterprising Mr. Moody, the Bumptious Captain Stamp, Morton describes Moody as “astute, determined – and perhaps a trifle puritanical.”

The prohibition attracted bootleggers and gutrot liquor and sent thirsty workers across the inlet to Gassy Jack’s saloon. One booze run led to an 1868 murder that ended in a hanging or a seven-year sentence, depending on which version of history you believe.

Moody built a personal estate alternately known as Invermere and The Big House, where he could oversee operations from his window.

But two days before Christmas, 1873, a blaze in the lamp room reduced the mill to ashes.

“There was no insurance and that the heavy loss will consequently fall altogether on the enterprising firm,” a newspaper noted.

Moody rebuilt over the winter but soon found himself targeted by newspaper wag J.K. Suter.

Suter took aim at what he took to be the incestuous relationship between business and government as suspicions arose regarding a Texada Island land grab.

Despite “denuding (the land) of its finest timber,” the lumbermen remain dissatisfied, Suter wrote.

“In fact, so puffed up with the idea of their own importance … that they absolutely boasted that they would send whom they pleased to represent us in parliament.”

An inquiry followed that would target Moody as well as Premier Amor De Cosmos, “whom custom requires us to dub honourable,” Suter wrote snidely.

While under questioning by a trio of judges, Moody talked little and said less.

“Have you any interest in land on Texada Island?” he was asked.

“I can’t say that I have,” he responded.

“Can you say that you have not?”

“I can’t say I have not.”

“Why do you not speak?” a judge exhorted.

One of his associates produced a note that suggested Moody was too ill to appear.

Despite his disastrous appearance, the royal commission found the “apparently suspicious” circumstances of the case weren’t sufficient grounds to establish guilt.

Moody’s life ended shortly after when he was aboard a paddle steamer, the S.S. Pacific, that collided with another ship during a November storm in 1875.

Just yards away from his Victoria home, a board washed ashore that was scrawled with his last words: “S.P. Moody. All lost.”

But the town he left continued to expand as lumber barons like Julius Fromme and John Hendry took over.

Hendry bought Vancouver’s first gas-powered automobile, preceding the city’s first gas station.

Hendry reportedly planned to sail on the Titanic but missed the boat to attend his daughter’s wedding to future lumber baron Eric Hamber, namesake of Hamber Island.

Moodyville was B.C.’s first city to be lit with hydroelectric power.

“These lights glitter tonight for the first time,” pronounced Arnold Kealy, District of North Vancouver reeve and the City of North Vancouver’s first mayor.

The lights, he said, “are a prophecy of greater things that will make us more than a second to the city across the inlet.”

The delicate art of getting everything named after you

No one gave the North Shore as much of his name as Arthur Pemberton Heywood-Lonsdale, a portly English investor who sported muttonchops that would have shamed a werewolf.

Lonsdale gobbled up real estate and spat it out again when an economic recession made paying taxes a questionable investment in 1894.

Alfred St. George Hamersley took over, coming up with $335 to run the seven-foot wide Lonsdale Avenue from the water to Eighth Street. Hamersley’s namesake avenue, St. Georges, was built just east.

As Lonsdale stretched farther up the hill, the advent of the streetcar made the city more egalitarian. While occasionally rolling into the water, the streetcar let workers buy cheaper land up north and ride to work, notes Shervin Shahriari in the book North Vancouver’s Lonsdale Neighbourhood.

Despite living in an East Third Street house Wells described as a “Swiss chalet on steroids,” Hamersley proved generous, donating much of the land that became Victoria Park.

The park was an integral part of the District of North Vancouver (the name was chosen over the objections of a contingent that favoured Burrard).

As the district looked to build, they looked to James Cooper Keith, a fired banker who was “willing to loan large amounts of money secured only by inflated real estate,” noted Tom Snyders and

Jennifer O’Rourke in their book Namely Vancouver.

Keith underwrote a $40,000 loan that led to the construction of Keith Road.

Besides the road, Keith left a legacy of cuckolded creditors. He died with a $500,000 estate and a debt of $1 million.

I do believe in ferries

In 1885, Charles Warren Cates was B.C. Ferries.

“Ferry service was to Lonsdale Avenue as a root is to a tree,” Shahriari writes.

When Vancouver was engulfed in flames in 1886, Cates’ ships hauled stone from Squamish and Gibsons for the rebuild.

Cates once ferried Francis Caulfeild to a West Vancouver spot clearly not named by the chamber of commerce: Skunk Cove.

A refined man who wrote his own translation of Homer’s The Odyssey, Caufeild created “a perfect English village,” Snyders and O’Rourke write.

He planted English oaks, built a badminton court and created an enclave ridiculed as the “fabled land of retired English colonels, croquet and tea and crumpets,” Wells writes.

Distinct from Caulfeild’s sensibilities was Scotland’s Robert Dollar, who emblazoned his ships with the dollar sign, summing up his philosophy nicely.

A rake of a man with a wide-brimmed fedora, Dollar made a bundle when his company moved supplies to U.S. troops fighting in the Philippines at the turn of the century.

Dollar, as Wells notes, “managed to profit.”

His workers rented houses for $15 a month, which got them electricity, daily mail service, their own garden, and access to a church whose minister was on the payroll.

Glorious, bastardized

Ki-ap-a-lan-u was a royal name.

It was Ki-ap-a-lan-u who greeted Simon Fraser.

But, as Wells puts it, the name was “bastardized into English.”

It was Chief Joe Capilano who took the issue of native rights to King Edward VII, meeting him in Buckingham Palace in 1906. The history is sketchy on the results of the meeting.

One hundred years after confederation, Chief Dan George, himself renamed in residential school, ruminated on the relationship between Europeans and First Nations.

“I have known you when your forests were mine. … When I fought to protect my land and my home, I was called a savage. When I neither understood nor welcomed this way of life, I was called lazy.”

But despite the disappearance of freedom and the emergence of customs he couldn’t understand, George ended his speech with a vision of equality.

“I shall grab the instruments of the white man’s success,” he promised. “I shall see our young braves and our chiefs sitting in the houses of law and government, ruling and being ruled by the knowledge and freedom of our great land.”

This article owes a debt to the works of Martin Wells, James Morton, Shervin Shahriari, and Tom Snyders with Jennifer O’Rourke. Incidentally, William Griffin was a builder who served on the District of North Vancouver’s first post-Second World War council after the 1931 bankruptcy. He was nicknamed Toaster.