A recurring intermittent headache triggers a memory for Eric Turcotte of that life-changing day four years ago when he lay motionless on the ice.

The other hockey players swirled around the 14-year-old splayed out by the boards, seemingly oblivious to the serious head injury at hand. A few seconds earlier Eric was celebrating a goal and making a beeline towards the bench for a shift change.

In the blink of an eye he was blindsided by a levelling bodycheck thrown by an enforcer from the opposing team and sent head-first onto the ice. Eric's mother, photographer Kaz Turcotte, watched the frightening incident unfold from behind her camera lens, capturing every sporting parent's worse nightmare.

Years later she is still haunted by the photo of Eric lying there, not moving. Her son hasn't been the same, cognitively, since the concussion.

"Like still mixing up letters and words," says Kaz, her voice heavy with emotion. "He also believes there are memories he has forgotten."

Eric agrees that his one concussion has had lasting effects. "I feel like I would have been a better speaker," he says.

During that "life-changing" October 2011 game, Eric was escorted to the dressing room in a disoriented state. He didn't know it at the time, but his rep career with North Vancouver Minor Hockey was over.

At the Lions Gate Hospital emergency room Eric was diagnosed with a sprained neck and a mild concussion. That was a Wednesday evening. The debilitating concussion symptoms didn't hit Eric until the following Sunday.

He couldn't form mental images and there was the mounting pressure on the back on his head.

"I felt like I was growing horns," recalls Eric. His worried parents went from one medical specialist to the next trying to find answers about their son's worsening condition. By that point Eric was experiencing persistent nausea, thunderous headaches and over-sleeping.

He says he basically sat in the dark for a month, making paper airplanes. Kaz would find them all over the house - in planters, behind chairs.

Eric's parents were also in the dark, figuratively. At the time doctors kept telling Kaz and her husband they didn't know much about concussions. That frightened them.

***

Recently concussions have become a hot topic in the medical community and in sporting circles, with many crediting NHLer Sidney Crosby, who suffered back-to-back concussions in 2011, for raising the profile of the issue.

"That's when people started talking because you've now got arguably the best hockey player who is not able to play the game he loves," says Dr. Shelina Babul, a renowned sports injury specialist with the B.C. Injury Research and Prevention Unit.

The recent movie Concussion starring Will Smith has linked repeated head injuries in the NFL to a risk of dementia. With concussions becoming part of the mainstream, attitudes shifted in the 10 years since Babul started in this field.

"It was the old adage you had your bell rung and you're going to be fine."

Concussions are now at the forefront of player safety conversations, as more studies on the risks of head injuries are being released. And parents and coaches are paying attention. Return-to-play protocols for concussions have become part of the amateur and professional sporting landscape.

"So we have come a long way," says Babul.

Lions Gate Hospital is a hotbed for concussion-related ER visits among youth.

There were 710 children and youth, from newborns to 19-year-olds, treated for concussions at Lions Gate from 2013 to 2015, the most of any Vancouver Coastal Health hospital.

Emergency room visits for children with concussions are on the rise, these recent B.C. Injury Research statistics suggest. This isn't to say there are more head injuries occuring, explains Babul, but rather parents are becoming more informed, exercising caution and getting their kids checked out.

Young boys were hospitalized at twice the rate of young girls in the Vancouver Coastal Health region, according to the recent statistics. Cycling (39 per cent), playground activity (12 per cent), and skiing and snowboarding (11 per cent) were the top sport and recreation-related reasons for concussion hospitalizations.

But as in Eric's experience, these children could be seeing physicians who are uninformed or still prescribing outdated advice for concussions, Babul argues.

Many physicians and bewildered parents have come to Babul for step-by-step instructions on how to effectively treat a concussion. The previous standard was to simply wake up the concussed person every two hours in the middle of the night. This is not the case anymore.

"The issue was that if you Google concussions you are going to get millions of hits," says Babul. "How do you know what's the most credible versus Joe Blow just putting up a blog?"

So what exactly is a concussion? In simplest terms it's a brain injury caused by a direct or indirect hit to the head or body, but it's much more complex than that.

Upon impact, the brain vigorously shifts or shakes and is knocked against the skull's bony surface. The grey area lies in the fact that concussions are difficult to diagnose. The brain damage can be so microscopic that often times CT and MRI scans don't pick that up.

Also, no two concussions are alike. Genetics, being predisposed to concussions and previous head injuries all come into play in recovery. While most people recover within two weeks from a concussion, 15 per cent of the population will have long lasting effects.

"There's no magic bottle of pills for a concussion," says Babul. "The treatment is absolute physical and cognitive rest. The idea is that you want your brain to reset and recharge."

The effects of concussions are cumulative, which is why doctors stress the importance of recognizing head trauma right away and being honest about symptoms. Staying in the game can lead to grim consequences.

"The idea is that when you sustain a concussion and you continue to play, you are now three times more likely to sustain a second, potentially more severe, concussion," explains Babul. "And if that concussion isn't recognized you are now nine times more likely to sustain brain damage and possibly even death."

Bubul points to a study that found 56 per cent of athletes polled would hide their symptoms just to stay in the game.

"You can't cast your brain like you can your foot or your arm. If you are feeling off you need to do something about it and not be a hero to your teammates, to your coaches, to your parents," she says.

In an effort to make credible concussion information more accessible, Babul and a team of experts worked with the province to develop an online, free-of-charge Concussion Awareness Training Toolkit. The website is broken down into different modules aimed at various audiences that deal with concussions - medical professionals, coaches, players, parents and school administrators.

The one-stop-shop includes the concussion basics, personal accounts of head injuries, as well as video lessons and resources to help prevent, recognize and manage a player's recovery. Cattonline.com also includes a 30-minute course that counts towards concussion certification training for doctors, coaches and volunteer parents.

Various soccer associations in the province have already starting using CATT. B.C. Hockey will vote this year on whether to make concussion awareness training mandatory.

Recently there has been talk in B.C. of legislating concussion protocols for youth, but Bubul says enforcing a law around concussions might be complicated. She would rather see consistent concussion policies throughout the sporting world and everyone, including medical professionals, on the same page.

***

Collingwood School is changing the game in North Shore high school athletics when it comes to concussion protocols.

Boys' football is the only high school sport that has specific concussion protocols, according to B.C. School Sports.

So, six years ago Collingwood took the initiative, sending three staff members including athletic director Dave Speirs and the school's nurse to a big concussion conference held annually in Niagara Falls, Ont. That province has pioneered concussion protocols for school sports.

"So basically we started stealing all the best stuff," says Speirs.

Piece by piece Collingwood administrators assembled injury prevention and treatment protocols for students, ensuring they have the latest research in their corner.

"If there's one thing about concussion management, it's that it's a very fluid area," says Speirs.

Two years ago Collingwood added to their injury prevention arsenal by hiring a full-time, certified athletic therapist, Gavin Leung, who works out of a sport clinic the school built into their new senior campus.

All athletes undergo baseline cognitive tests done at the beginning of the season, with results cross-referenced during retesting to see if there has been a change in areas such as memory, concentration and reaction time.

Leung is also a fixture on the sidelines during Collingwood sporting events, watching out for concussions but mostly he is called into action to tape up injured players. During away tournaments, Leung also travels with the school's various teams and can be found running a clinic out of the hotel room.

Rugby and football tend to get a bad rap when it comes to concussions, but as Speirs explains head injuries don't discriminate in sport.

"It's just as likely for a senior girls' soccer player to sustain a concussion or a field hockey player to get a ball off the head," said Speirs.

The veteran high school coach says concussions are a serious business these days.

"No one is playing around with people's brains anymore," says Speirs.

"It's not even remotely the same world as it was even 10 years ago, never mind 20. Ten years ago there was not a business about concussions, whereas now there's all kinds of clinics across Vancouver where they promise to help your child get better from a concussion."

Speirs remembers a time when a kid came off the field, eyes rolled to the back of his head, and the next day he tells the coach a doctor gave him an all clear.

Today there are safeguards in place at Collingwood, called Return to Learn, Return to Play protocols, based on discussion at a concussion symposium in Zurich.

If a concussion is suspected, the coach makes contact with the parents who are given a package. Included in it are forms for a doctor's diagnosis and treatment recommendation that goes on file at the school.

The concussed student is then slowly integrated back into school and sports. The process itself doesn't start until the student is symptom free.

You don't want that second concussion, says Speirs.

A big issue Collingwood experienced a few years ago was having athletes not reporting concussions sustained outside of the school setting before jumping into the next game.

"We had kids that were in a bad way," says Speirs.

B.C Hockey's chief executive officer Barry Petrachenko agrees the sporting world has changed since Crosby's concussions. He says optics have a lot of do with that.

"So if our players see a big hit in the NHL and potentially a dangerous and reckless hit and that's accepted, then it trickles into minor hockey," says Petrachenko.

Minor hockey rules have adjusted to cut down on concussions. Head shots are not tolerated. In 2013 Hockey Canada banned body checking at the PeeWee level and below. Harsher penalties are being doled out for aggressive offences, with a graduated system of discipline as a way of targeting certain behaviours, says Petrachenko.

Regulation is important but the true change, says Petrachenko, is that "overall society understands now that it's not a sign of weakness that you have a concussion, and that concussions are a real issue as opposed to a badge of honour."

North Vancouver native and former NHLer Paul Kariya spoke to ESPN.com about his decision to hang up his skates in 2011 after sustaining a couple of bad concussions.

"Whatever it is I'm going to do, I'm going to need my brain to do it," Kariya told ESPN.

Kariya reportedly took up ballroom dancing to help his brain rehabilitate, along with hyperbolic chamber therapy, working with American concussion expert Dr. Daniel Amen.

Sports can have a powerful grip on athletes, to the point where they don't realize it might be time to step away.

Longtime North Vancouver soccer player Lee-Ann Denham has sustained a whopping 13 concussions.

She had her bell rung the hardest five years ago while playing in a co-ed soccer match. "It was pretty big. That's when things became a little more (serious)."

A male player, attempting to kick the ball from one end of the field to the other, made contact with Denham's head on the way through. She was standing close to where he kicked the ball and she absorbed that force with her skull.

"I was definitely dazed," says Denham, who spent eight months in a mental fog. After sustaining back-to-back concussions in 2015, Denham was out for a full year.

"The main thing after the last few concussions is that it's affected my vision the most," reveals Denham.

She also struggled to return to work - which is soccer.

Denham coaches for the North Shore Girls Soccer Club and knows what concussion warning signs to look for. She gives the example of seeing an 11-year-old girl badly concussed during a game last spring.

The normally bubbly 11-year-old appeared withdrawn. That girl's concussion sparked a dialogue within the North Shore Girls Soccer Club's board and the overall organization, says Denham.

"They decided they should probably have a clear (concussion) policy," she explains. All the talk of concussions hasn't stopped parents from putting their kids in the sport, says Denham. In fact she thinks the enrolment numbers are growing.

"I think the benefits outweigh the risks," says the longtime soccer enthusiast and one-time Capilano College player. "When the fog clears you kind of realize I've gotten so much from the sport."

***

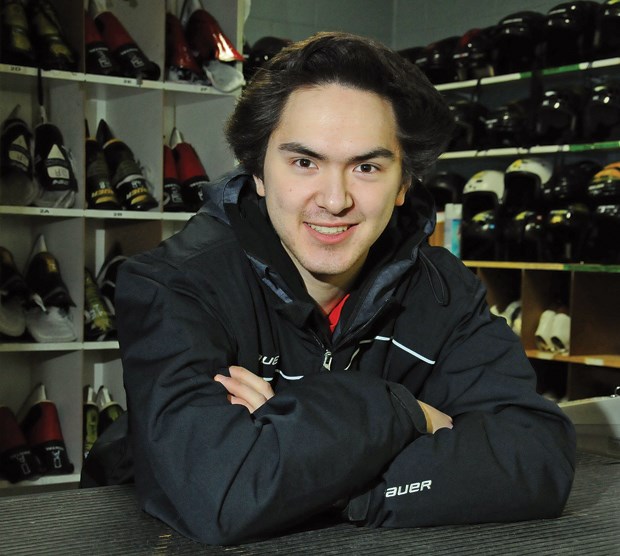

Eric Turcotte, now 19, still maintains a relationship with the sport he says he will always love.

He teaches introduction to hockey classes for kids at Canlan Ice Sports North Shore, where he also works in the skate shop, as he saves up money for school.

Turcotte, who has an affinity for 3-D computer modelling, is hoping for a career in the gaming industry.

He still laments that cheap shot from the enforcer on the opposing team, who was eventually kicked out of minor hockey for too many offences.

"It changes your life I guess. Sports ain't my main thing anymore," says Eric, who once dreamt of a professional hockey career and following in the footsteps of his dad who played in university.

It pains him not to rush up and down the ice anymore, but he still watches hockey from the sidelines, playing the game out in his mind.

"Mostly I think about what I would do if I was out there right at that minute?" he says. "How would the game change if I was just out there?"

Click here to find Part 2 of our series, a look at how several Lower Mainland doctors and researchers have responded to the concussion crisis with innovative new technologies aimed at making athletes safer.