The helicopter hovers over an icy and barren landscape on the slopes of an active volcano, the pilot searching for a patch of snow that won’t act as a trapdoor to a massive, chopper-eating crevasse.

The camera is rolling, ready to capture disaster.

“It’s a rough place,” a voice says over the sound of the rotors. “Either you’re safe and you come home, or you screw up and you don’t come home.”

The helicopter does a “bounce test,” touching down briefly and then lifting up again to see if the snow remains stable or falls away into frozen nothingness.

Everyone in the helicopter is following the lead of North Vancouver native Graham Hill, a Seycove secondary grad whose research on volcanoes has taken him to the bottom of the world where he has become an unlikely reality TV star. Hill’s project is one of a handful featured in a National Geographic Channel series called Continent 7: Antarctica.

Hill is there to study Mount Erebus to learn more about how volcanoes work in hopes that his research will help save lives in human populations near active mountains around the world.

National Geographic is there to watch and learn as well, although as you listen to the narrator describe the situation, it’s obvious they’re also drawn by the danger of Hill’s work. Could one of Antarctica’s famously fast-moving storms sweep in and bury the team? Could a scientist take two steps in the wrong direction and fall into a crevasse? Heck, they’re on the side of a volcano – what if Erebus decides to erupt while they’re knee-deep in snow on its frozen slopes?

The helicopter touches down again, the pilot satisfied that they’re not all going to plunge to their deaths. The door slides open and the team is greeted by the sting of -40°C air.

Welcome to Antarctica.

• • •

Dr. Graham Hill, a senior fellow with the Centre for Antarctic Studies and Research at the University of Canterbury in New Zealand, first set foot on Antarctica back in 2009. The thing that stands out about the moment is not a thing at all, but rather a colour.

“The first time you get out of the plane, it’s quite dramatic with how white everything is,” Hill says during a long conversation with the North Shore News. It’s early February, and he’s just returned from his third and final Antarctic summer for the Mount Erebus project. In each of the past three years he spent more than three months on the frozen continent, an area that is devoid of many of the modern conveniences we all take for granted. Forget cellphone coverage, cable TV or WiFi – if you do manage a computer connection to the outside world, you’re on dial-up that can support nothing more than a short, text-based email.

“You’re not watching YouTube clips or anything like that,” says Hill with a laugh.

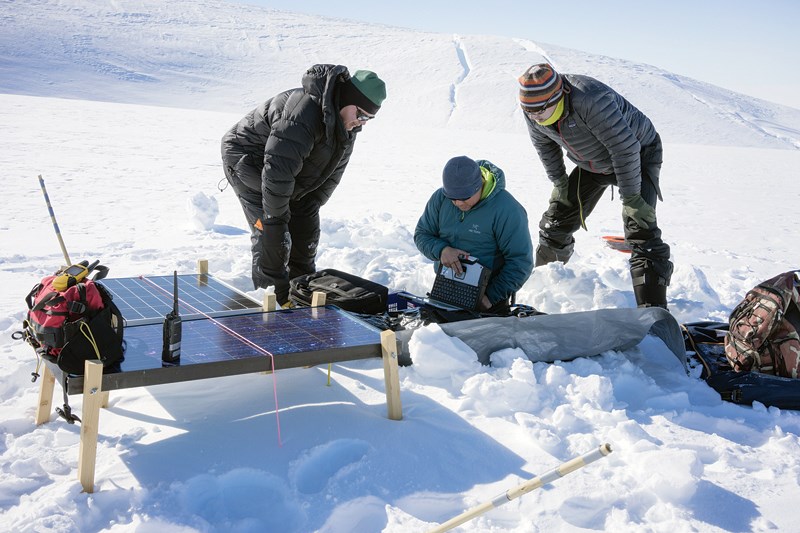

But he wasn’t there to watch cat videos. Antarctica was a long business trip for Hill, whose task was to place and then recover 132 high-tech data collectors at sites scattered all over Erebus. The data collected from each site will be woven together to reveal a map of the inside of the volcano – essentially an MRI of a mountain.

It may seem strange considering that Antarctica is one of the most inhospitable places on the planet, but Hill chose it as the site of his research due to its easy access. Getting to the continent can be tough, but once you arrive, there are seven helicopters ready to go, and Mount Erebus is just a 15-minute ride away from New Zealand-run Scott Base. And unlike other active volcanoes, Erebus isn’t burdened by such inconveniences as trees, brush or people.

“It’s probably the most logistically accessible volcano in the world,” says Hill. “It’s actually really accessible – once you get there.”

Erebus is also a mystery worth unravelling because it shares rare traits with some of the deadliest mountains in the world.

“Erebus is a weird volcano, it erupts a weird chemistry,” says Hill. “It’s poorly understood. It’s very low in the traditional components that make a volcano explosive, so it’s not a water-driven system, it doesn’t have a high quartz content in it. So it’s driven by carbon dioxide and … aluminum-based elements. These can erupt very explosively.”

Similar systems can be found in Mount Vesuvius, the mountain that buried the city of Pompeii and its roughly 2,000 inhabitants in 79 AD, and Mount Tambora on the Indonesian island of Sumbawa, home to an 1815 blast that is the deadliest on record and also one of the most powerful.

“That killed a lot of people,” says Hill. All numbers are estimates, but the Tambora eruption is believed to have instantly killed approximately 10,000 people with another 60,000-90,000 dying of starvation or disease shortly thereafter.

Hill is hoping to better understand these blasts by examining Erebus from the inside out.

“We have this stuff erupting in a very controlled fashion in Antarctica, so it’s a good place to try and study it, figure out where it’s being sourced and how it relates to the underlying tectonics that are going on there.”

• • •

In the second year of the Erebus project, National Geographic showed up on Antarctica to begin filming their Continent 7 series. Hill and his team were doing cool stuff with helicopters and fancy computers, so they were thrust into the spotlight.

“We didn’t really have much of a choice,” he says. “We were told. … I think they choose us because they thought it was something that people could relate to. And it would look good on TV.”

Season 1 of the series aired last fall – encore showings will appear on the National Geographic Channel starting March 21 – documenting projects such as researchers tagging whales with underwater cameras, a trek to the middle of the Ross Ice Shelf to set up a new camp, and a U.S. Coast Guard icebreaker cracking through 10-foot-thick ice to open up a shipping channel.

Hill has seen the first two episodes of the series and says it was cool to watch his South Pole pals on the screen, if not himself.

“I don’t know if it’s my favourite thing I’ve ever done,” he says about talking on camera. “It’s never fun watching yourself. But the people that I saw it with seemed to think it was done pretty well.”

Hill readily admits that the docu-series does follow the standard reality TV tropes of turning every vague deadline into a life-altering make-or-break point, and emphasizing the worst-case danger in every situation.

“They of course skewed it to try to sell the tickets,” he says, adding that hovering in a helicopter on the steep slopes of an Antarctic volcano actually doesn’t faze him that much. “They’ve got really good pilots. You’re in good hands.”

The dangers of the work, however, are real. The show depicts mountaineer Danny Uhlmann, the man whose voice warns of impending doom, leaving the helicopter as a scout to make sure there are no hidden dangers in the work area. He’s on skis so that his weight is spread out, decreasing the chances that he’ll bust through the snow and fall into a crevasse.

“I’ve had very close friends die in crevasse falls in situations just like we’re dealing with here,” Uhlmann says on the show.

Once the work site is secure, Hill and his research partners must do fine-motor work with expensive sensors and computers while contending with snow, ice and temperatures that routinely hover around -40°C and can dip down even lower.

“It’s tough on the hands, that’s for sure,” says Hill. “There are times when your hands get really cold and you just have to stop what you’re doing and put them inside a jacket or something for a few minutes.”

The biggest danger, says Hill, is Antarctica’s famously fickle weather. Winds can whip up in an instant, and if conditions get too bad it can be impossible for a helicopter to take off or land.

“It can change in 15 minutes,” says Hill. “It can go from beautiful blue sky to ‘you’re not going anywhere’ in a couple of minutes.”

The team was always prepared to spend the night on the mountain and it got dicey a few times.

“We got stuck for hours at a time, but never overnight,” says Hill. “We got close a few times.”

They got their data, though – Hill and his team are done with Antarctica and have moved back to civilization to start analyzing the data. At the moment the scientist, who has a PhD in geophysics, has no idea what mysteries will be revealed once they’re done.

“All we know is that we’ve collected good quality data at this point,” says Hill. National Geographic has collected some good stuff too – they filmed Season 2 of the series this year and will likely release it next fall.

Hill knows what they filmed but says the finished product will remain a mystery to him until he sees it on the screen.

“You don’t have a clue,” he says with a laugh, adding that the thought of making an on-screen gaffe still makes him nervous. “It’s not the best thing, (although) it’s in their interest to not make you look bad.”

One thing that never looks bad is the backdrop – there’s a reason why National Geographic chose Antarctica for the series. It’s one of Earth’s last great pioneer fronts, the only continent with zero permanent residents. Everyone who goes there can feel the magic of the land, the thrill of stepping into shelters set up more than a century ago by legendary explorers, of setting foot on ground that has never before felt a human footstep.

“It’s a very special place to go and work,” says Hill. “There’s a lot of history there when you get to visit places like the Nimrod Hut and the Discovery Hut and all those things from Shackleton and Scott 100 years ago. You get that sort of appreciation because you go to those places and it looks like they could have walked out of there a few days earlier. It’s a privilege to get to go and work in a place like that.”

• • •

Season 1 of Continent 7: Antarctica will re-air Tuesday nights at 9 p.m. starting on March 21 on the National Geographic Channel.