After more than a year of being distant and uncommunicative, Ada is back.

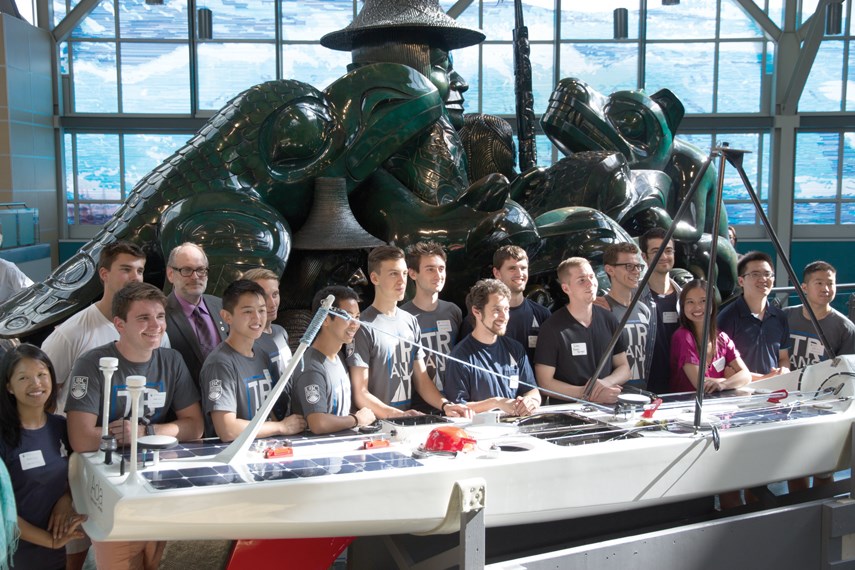

Built by University of British Columbia students, the unmanned, self-navigating, robotic sailboat, or sailbot, went adrift in the summer of 2016 during a planned trip from St. John’s, N.L. to Ireland.

Lions Bay resident and UBC alum Arek Sredzki remembers the launch and loss of Ada, a 5.5-metre vessel named for Ada Lovelace, the mathematician and visionary who wrote a machine algorithm in 1843 that is often considered the first computer program.

As the lead on the software team, Sredzki oversaw path planning, controls, and obstacle detection for Ada, who was designed to be the first unmanned, robotic sailboat to cross the Atlantic Ocean.

Given that the vessel might need to spend months floating in the open ocean, the power supply in the boat was limited. Ultimately, the team opted for infrared cameras, which they anticipated would be particularly useful for steering clear of icebergs.

For the 67-member team, the club evolved into a full-time job.

“I honestly hadn’t slept at all for two weeks before we launched,” Sredzki recalls. “Perhaps even half an hour before we launched I was working.”

With a sailing background from his days at Eagle Harbour Yacht Club, Sredzki was anxious to combine his knowledge of racing techniques and software engineering.

After spending one last night working on Ada’s tracking system, Sredzki watched – sleep-deprived and hopeful – as Ada sailed for emerald shores.

“If only the winds hadn’t been quite so strong and Ada so fast, I think she would’ve made it in maybe less than half the time than we originally expected,” Sredzki notes.

The 5.5-metre vessel of wood and carbon fibre got off to a flying start, Sredzki recalls, noting she was purring across the waves at about 12 knots, or 23 kilometres per hour.

“I really wish I could’ve seen her flying over the water,” he says.

While contact was on and off over the course of the journey, the first serious snag came about 1,000 kilometres into the trip when the team lost control of Ada’s steering.

Rudderless, Ada rolled with the current, heading south into a three-day storm.

The team lost contact.

“We really weren’t sure we would hear from her again but then, a couple of days later, she came back online, which was a huge relief.”

The team used satellites receiving Ada’s data to triangulate her position.

While an Irish greeting was increasingly unlikely, there was a period where it looked like Ada might make landfall on the coast of Portugal or Spain, according to Sredzki.

But the currents started pushing her south and then all contact was lost.

But the sea has a long memory, and on Dec. 1, Sredzki was inundated with messages from his past.

The crew of the research vessel Neil Armstrong had snared their boat off the coast of Florida.

“Unbelievable,” he remembers thinking. “It seemed too good to be true.”

While “she’s a little battered,” the hull and keel are still in excellent condition, Sredzki reports.

While other UBC students are hard at work on Ada 2.0, Sredzki is currently working on self-driving electric cars at NIO in San Francisco.

Joining a student engineering team is something that he would highly recommend, says Sredzki. “I think that’s the sole reason why I was able to get internships at Tesla (and) Google.”

And while he may not be personally involved, he hasn’t forgotten Ada.

“After that, I hope that she can sail again.”