From West Vancouver, four young scientists watched (and one likely slept) as 5,000 kilometres away the Falcon 9 rejected gravity’s grip and took their worms to the stars.

On Feb. 19, SpaceX’s rocked blasted off from the same Florida launchpad where the Apollo missions of the 1960s turned science fiction into science fact. The launch was historic, but for Grade 7 and 8 students Kristopher Kirkwood, Griffin Edward, Shania Farbehi, Vesal Farahi, and Joseph Piovesan, it was also just part of their class science project.

“It was awesome,” Kirkwood says of the launch.

“Finally,” Farahi echoes.

“I just forgot about it completely,” Piovesan says. “I think I was sleeping.”

In an effort to find out if worms could play a role in a zero-gravity garden, the team put in hours of work, consulted local experts and dug into the Westcot Elementary dirt for astro-earthworms. But as that rocket soared out of Cape Canaveral they could only look up and imagine how their cocoons were faring atop nine engines creating 7,607 kilonewtons of thrust.

After being scheduled and rescheduled, the rocket was literally seconds from blastoff on Feb. 18 when the launch was scrubbed, reportedly due to what SpaceX owner Elon Musk described on Twitter as the “slightly odd” movement of an engine steering hydraulic piston.

“We were up at 7 a.m. waiting for the launch,” Kirkwood recalls. “When they got to nine (seconds left) they suddenly had to just shut everything down.”

“I woke up for nothing,” Farahi recalls with a laugh.

But the next day the rocket launched the Dragon spacecraft into orbit, which in turn delivered about 5,500 pounds of food and supplies to the crew on the International Space Station.

That payload included the team’s experiment: a tube filled with dirt and worm cocoons. The experiment was meant to answer a simple question: Can worms grow in zero gravity?

The question could be critical, Kirkwood explains. If astronauts using composting toilets could combine worms and human waste they could create fertile soil 400 kilometres above terra firma - relieving space agencies of launching supply missions like the one their experiment was part of.

It was an important question, but to pursue an answer, the team had to submit their experiment through the Student Space Flight Experiments Program, a U.S. and Canadian program designed to foster an interest in science, engineering and math. The top prize for the program, which came to the West Vancouver school district largely through the efforts of Westcot vice-principal Matt Trask, was a chance for students to send their experiment into space.

After compiling what Edward described as “at least 10 Shakespeares worth” of research, the Westcot team edged out about 100 similar groups across West Vancouver. That victory gave the team the chance to make the case for their experiment to NASA engineers at the Smithsonian Institution Building in Washington, D.C.

“At the very beginning I thought, ‘Well, this is pointless,’” Kirkwood says. Why should he help write a huge proposal when the team head “almost no chance” of winning, he wondered.

Still, he asked his mother if they could go to Washington, D.C., you know, just in case they won.

“She said, ‘Well, yes,’ because she thought there was absolutely no chance,” he says, eliciting laughs from the team.

With four team members present (Farahi was represented by a picture the group carried on stage) the NASA engineers handpicked the worms to be one of 21 experiments included in the launch out of 2,400 submissions.

After the launch and a successful re-entry, the students had the chance to open their well-travelled experiment.

“It was super-cool to be holding something that has been on the space station,” Kirkwood recalls.

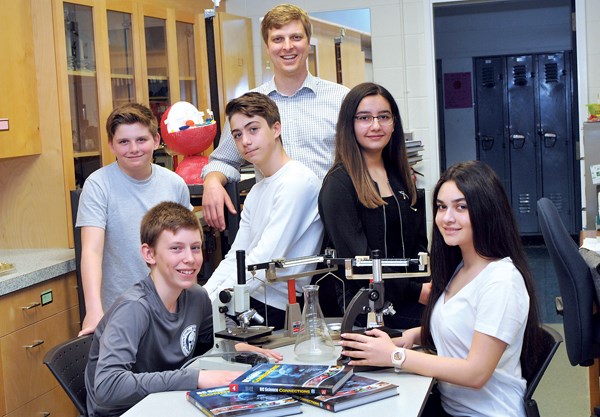

In a Sentinel Secondary classroom the team meticulously photographed every stage of the unwrapping before placing the worm tube on a fume hood to avoid inhaling the formaldehyde-like solution used to preserve the worms.

While the cocoons hatched, the team couldn’t find any trace of their worms under a 3D microscope.

“It’s kind of a mystery,” Piovesan says, hypothesizing the worms may have suffocated.

While the team agrees the worms decomposed, the lack of any remains is a bit baffling. However, Westcot vice-principal Matt Trask – who worked with the team throughout the experiment - quickly dispels rumours there might be West Vancouver worms “floating around” the ISS.

Farahi sums it up simply: “So many questions and no answers.”

Overall, the experience felt like “sci-fi action drama,” according to Edward.

“I’m surprised that this experiment was so long,” he notes. “It went from me in Grade 7 studying Newton’s laws to a cow-eye dissection yesterday in Grade 8.”

The project gave the team a chance to explore “real science,” Trask explains.

Teachers often default to “cookie cutter” experiments with predictable outcomes, he says.

“That’s not real science, that’s cooking, that’s following a recipe.”

Kirkwood agrees, noting that the previous extent of his scientific education was looking in the textbook for answers.

“It made me change my view because I always thought … if you did an experiment the same thing would happen every single time.”

The year-long experiment gave Farbehi a new appreciation for scientific inquiry.

“I never liked science before last year,” she says. “I was never very good at it and I didn’t have a lot of great science teachers.”