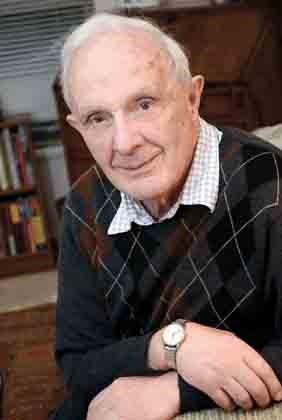

After a day exploring the outdoors, young Hugh Hamilton's pockets would be crammed with creatures.

Inevitably few survived the experience, but Hugh's interest in the natural world thrived and would influence the course of his life.

Hugh was born in 1929 in Simla, India, where his father was a forester with the Indian civil service and his mother was involved with the Girl Guides. It was a life straight out of the British Raj overlaid with Kipling's The Jungle Book. On family excursions, Hugh and sister Sylvia rode in panniers balanced on either side of a yak.

When Hugh was five and Sylvia seven, in keeping with British custom, they were sent home to England to be educated. In 1940, their schools were evacuated to Canada, the siblings crossing the Atlantic in separate naval convoys. A year later, Hugh went on to his aunt, educator and naturalist Helen Seth-Smith, in Washington, D.C. During the summers, everyone drove west to the family cabin. High in the Colorado mountains, close to the Great Divide, Hugh was in his element, fishing, hiking, birding and forming a life-long interest in Aboriginal cultures of the American southwest, which he and his wife Jane later passed on to their own children during visits to the cabin.

In 1943, Hugh returned to England aboard an aircraft carrier escorting a supply convoy. The crew assigned the 13-year-old a place on the vessel's bridge where he stood U-boat watch every day.

At school, Hugh was more interested in training and flying a kestrel falcon than in his studies. Skilled poachers, Hugh and his mates supplied the masters with rabbits, a welcome addition to the food ration. His preference for the outdoors resulted in frequent canings, somewhat alleviated by the strategic placement of rabbit skins.

Hugh's parents visited their children whenever possible. His father, now inspector-general of forests, stayed on in India through Partition. It was not until 1949, when Hugh had completed his national service, that the family was reunited.

"Suddenly we were a family, with a mother to love us and a father to instruct us and a home where we could all be together," he says.

Like his father, Hugh studied forestry at Oxford where he formed two important friendships: Jane Brockman was a student at the school of occupational therapy and Tony Jarrett with also in forestry.

In 1951, Jarrett and Hugh hitchhiked across North America to British Columbia, worked for the ministry of forests over the summer, hitchhiked back across the continent and returned to school.

Their future was influenced by the University of British Columbia's Harry G. Smith and Vladimir Krajina. Hugh's father supported his decision to work in forestry in British Columbia. "My father had India and the colonial service. My opportunity would be in Canada," he says.

As fate would have it, Jarrett and Hugh were working in the Caribou when they learned Jane was working in Vancouver. Hugh and Jane married in 1960 and made their first home in a log cabin situated north of Williams Lake and south of Quesnel.

In 1964, they purchased the house in West Vancouver that was home for the next 49 years. Here their children learned about the sex life of snails and other marvels of the natural world, usually while perched in a tree.

His work in forestry took Hugh throughout the Caribou and central British Columbia until 1996 when he made the innovative decision to sell his forestry consulting firm to his employees.

Hugh continues to explore B.C. on an annual hiking excursion with Nature Vancouver. Nearer home, Hugh volunteers with West Vancouver's Streamkeepers, Shoreline Preservation and Old Growth Conservancy societies. He received the community's heritage achievement award in 2009.

As B.C. Heritage Week closes for another year, it's important to appreciate the contributions of volunteers like Hugh towards the preservation of the natural heritage that surround and sustains us.

Behind Hugh stand a host of people - his parents, his aunt Helen, gamekeepers and poachers, Navajo, Hopi, Dene and Coast Salish people, foresters and ecologists - who taught him about the natural world and its wonders. Now Hugh's greatest reward is in sharing what he has learned. Like other elders among us, the wisdom and knowledge Hugh acquired over his life is his legacy and his gift.

Laura Anderson works with and for seniors on the North Shore. 778-279-2275 [email protected]