This story has been amended.

He saw the North Shore, and he saw what the North Shore was becoming.

With his engineer’s gaze and ever-present camera, John Barber Holdcroft chronicled North Vancouver at a time when swamp was swapped for shopping and the Second World War shipbuilding boom precipitated a sea change on the port.

Slated to begin Feb. 24, a selection of Holdcroft’s photos are set to be displayed at the Community History Centre on Institute Road in Lynn Valley.

Writing for an engineering publication in 1969, Holdcroft recalls arriving in Victoria in 1904 as a 10-year-old boy. An epoch when Canada was lacking “any premonition of the tremendous surge of growth and industry we now see developing,” he writes.

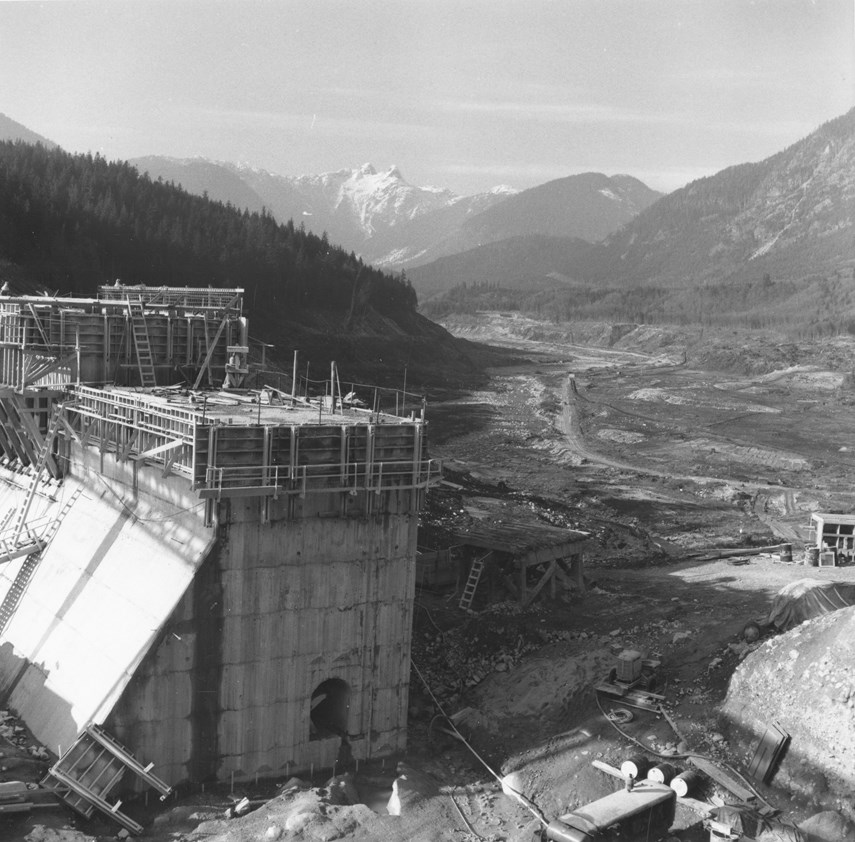

But Holdcroft’s photos seem proof of his own premonition – or at least best guess – of what the future held. He snapped a picture of Cleveland Dam when it was a dry dream amid the mountains. He shot the Lions Gate Bridge when it was a tapestry of steel stretching towards the mainland; silently promising to solve transportation problems.

The view of the bridge is striking, North Vancouver Museum and Archives reference historian Daien Ide remarks – not least because it’s unclear where Holdcroft might have stood to get the shot.

“His design sensibility as an engineer, that came through in his photography because he’s picking up a lot of details, particular angles, the scope and . . . the sheer size of things,” Ide says, sifting through his photos.

With elastic towers of smoke and ash in the background and a young observer in the foreground, Holdcroft’s view of Vancouver’s 1938 waterfront fire resembles a Viking funeral.

“He was just using a regular camera . . . but always finding that moment, that best light and best angle,” Ide notes.

The observer adds scale to the picture but the observer’s face remains a mystery. Even Holdcroft’s wife and daughters seem to struggle for primacy in his compositions as swollen clouds and straining structures loomed above them.

“You don’t get the usual family shots where it’s: ‘OK, everybody get together, smile!’” Ide notes, discussing the distinct nature of his black and white scenic photos.

“When you can have the body of work from one photographer in one place and get a sense of the breadth of interest, their life, all in one place; that to me is a very nice, rounded, personal record,” she says.

During the 1920s and ’30s, the Holdcroft family home at 832 Cumberland Cres. was nestled between dirt roads and “swampy jungle,” according to daughter Mary Frances Holdcroft.

It was a time when a car trundling down their narrow street was noteworthy and when streetcars were “our link with the larger world,” Mary Frances writes.

She also described a fog that rolled in on giant

feline paws.

“In those days the fog was real fog,” she assures us, recalling ferry captains baffled by grey soup and the bells of the streetcars reverberating amid the pillowy mist.

The home was one of six Edwardian-style craftsman houses designed in 1911 that formed a low-density community.

The Holdcroft family was “very close-knit and unusually self-contained,” Mary Frances writes, describing her parents as being bonded by their “unshakeable faith in God.”

Holdcroft’s Christmas cards featured scenic photos and biblical scripture. Mary Frances remembered her father at the pipe organ, nurturing a fascination with organ music that arose from his boyhood years amid the cathedrals of Brussels, Belgium.

“I heard enough of the mysterious breathing of organs in great, ancient churches to make pipe organs . . . a life-long keen interest,” Holdcroft writes.

As a young man in Canada, Holdcroft worked 60-hour weeks as a rodman and chainman, lugging surveying equipment over his shoulder as though it were heavy artillery.

Looking back on those days as a 75-year-old man, Holdcroft touts the effect of hard work.

“There was no teen-age problem then,” he writes, perhaps thinking of the young people of the late 1960s.

While Holdcroft served as a lieutenant in the 6th Field Engineers during the First World War, he stayed close to home, only explaining his health did not meet: “the then standard for overseas service.”

Following the war, his engineering career with Pacific Coast Pipe took him across Canada, “always with a camera slung over his shoulder,” Mary Frances recalls.

The resulting pictures are the best kind of hobby photographs: a significant record of place and person, Ide says.

It was, “a mighty privilege, to live in the closing years of one age and the opening ones of another,” Holdcroft writes. He describes the emergence of central heating, typewriters, safety razors, and all the things we now take for granted.

“And so change marches on,” Mary Frances writes. “The swamps and skunk cabbages on the flats have given way to the large Capilano Mall development.”

Describing his perspective on change, Holdcroft quotes a bible passage from the Book of Daniel.

“Many shall run to and fro, and knowledge shall be increased,” he quotes. “There are no endings; each phase of life through the years, as dictated by the great sociological changes taking place through my lifetime, have given place to a new beginning.”

This story has been corrected since first being published. Holdcroft arrived in Victoria in 1904, not 1894.