It is commonly understood that a samurai is a sort of Japanese knight-at-arms, albeit one dressed in lacquered armour rather than steel.

This is only sort of true: in point of fact, the samurai class extended to artisans, scholars, musicians, and cars. Well, OK – that last one didn’t happen overnight.

However, there really was a car called the Samurai – two if you count the adorable little trucklet Suzuki produced. However, in this case, I’m talking about a racing machine that was the product of pan-Pacific co-operation, and one that should be of interest to any modern fan of Japanese performance. It’s called the Hino Samurai, it was engineered by BRE’s Pete Brock and built by Troutman Barnes, and it should have been a world-beater.

Hino is probably a company you know nothing about, unless you’re interested in commercial trucks. Hino is currently a subsidiary of Toyota, and even has a Canadian division out East producing cube vans and

the like.

In the early 1960s, however, they were part of Japan’s fledgling car industry. Their first real effort, the Contessa, was based on the Renault 4CV, and was crammed with ennui. It was a sad little automobile, and only worth mentioning for one reason.

Brought over to the United States by a Japanese-American actor who wanted to give racing a try, the first generation Contessa was turned into a pretty decent sedan by Brock Racing Enterprises. Pete Brock will be a recognized name among both old hot-rodders and Datsun fans in the audience: he turned Shelby’s Cobra into the streamlined Daytona coupe, a winning racing machine that’s now staggeringly valuable.

In the early 1960s, the newly formed BRE was still looking for smaller projects, and they managed to get the homely little Contessa on the podium once or twice. Seeing this, Hino’s brass decided to let BRE have a crack at the next-generation Contessa, a much more convincing affair with a 1,300 cc engine, and better engineering.

The result was something like the racing versions of the Renault Alpine A110. BRE showed up with two Hino Contessas at the Mission Bell 100 in 1966, and promptly beat the pants off the established marques. The crowd was stunned – heretofore Japanese cars had been economical and cheap (emphasis on cheap, and not in a good way).

Hino, of course, was pretty excited, and set about getting BRE to work on Contessas for further racing efforts. They also set aside funds for a secret racing project.

However, things were not so rosy over in the accounting department. Neither Contessa had done well sales-wise in Japan, and Hino was in a pretty precarious situation. The only thing keeping them going were their bus and truck sales, and the strong interest in a Contessa-based pickup called the Briska.

The public weren’t the only ones eyeing the Briska, Toyota was too. Seeking growth, Toyota aggressively pursued many smaller companies during the ’60s and ’70s, and had set their sights on Hino.

While BRE worked on their secret project, Toyota began weaving a web to entangle Hino’s assets.

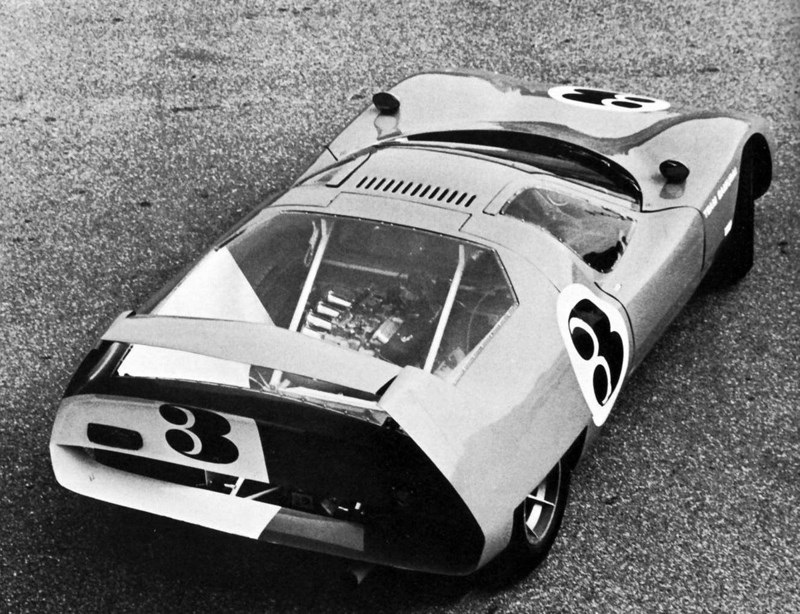

The result of BRE’s engineering, the Samurai, was revealed before the 1967 Japanese Grand Prix, to the shock of everyone. Based on a racing chassis, it featured the aerodynamic bodywork Brock was known for, with a high-revving, small-displacement four-cylinder mounted amidships. It was extremely light, fast and agile, and looked to do well in its class at the Grand Prix, against the likes of Privateer Porsche 904s. Eventually, the plan was to run the car at the 24 Hours of Le Mans.

Well, Toyota couldn’t have Hino’s stock price shooting up just as they were about to buy the company. Fuji Speedway was linked with Toyota, and it just so happened that most of the racing scrutineers were Toyota employees. Totally mysteriously (wink wink nudge nudge), the Samurai was declared illegal to race for being too low. Indeed, it did ride with little clearance, and even threw sparks while banking hard while testing.

Despite being denied a fair fight, the little Samurai got plenty of publicity. Thanks to legendary actor Toshiro Mifune stepping in to play the part of honorary race team captain, the Japanese press made much of the BRE team. The excitement even made its way across the Pacific into the major enthusiast publications, thanks to Brock’s previous reputation with the Shelby Daytona.

Toyota bought Hino and cancelled the Samurai program, but promised Brock the chance to work on their 2000GT racing effort. However, at the last minute, they gave the racing contract to Shelby. Brock was furious, but his Hino connection had one more trick up its sleeve.

Datsun USA wasn’t interested in racing their cars, having had a disappointing season. Datsun Japan just happened to have a CEO who was school friends with a Hino executive. Some back channel communications took place, and BRE received a couple of Fairlady Roadsters and funding direct from Japan.

The BRE team showed up at the races with their prepped open two-seaters, trailering them in the Hino truck they’d used for hauling the Contessas around. The Toyota 2000GT wasn’t in the same class, but BRE ran against Shelby on the circuit occasionally, and the little Datsuns punched above their weight. At the end of the season, the 2000GTs were beat out by Porsche, while Datsun won its class.

After that, BRE and Datsun wrote their way into the history books, with racing victories for the 240Z and 510, both legends now. The 510 especially proved that Japanese cars could be the real deal, even if they

were inexpensive.

As for the Samurai, it ended up competing in private hands, then disappeared after a restoration project stalled. However, I’m happy to report that somebody sent me a picture of it last week, and it’s mostly complete.

Hopefully it won’t be long before this long-lost machine is hauled out of the California garage where it now lurks and reassembled as the part of history it is. Just because the samurais are no longer with us, doesn’t mean we shouldn’t honour the way they changed our history.

Brendan McAleer is a freelance writer and automotive enthusiast. If you have a suggestion for a column, or would be interested in having your car club featured, please contact him at [email protected]. Follow Brendan on Twitter: @brendan_mcaleer.