Two by Shirley Clarke: The Connection (1961) and Ornette: Made in America (1985) in newly restored 35mm prints from Milestone Films and UCLA Film & Television Archive. Screening at Pacific Cinémathèque Oct. 27-29 and 31. For more information visit thecinematheque.ca.

John Goodman

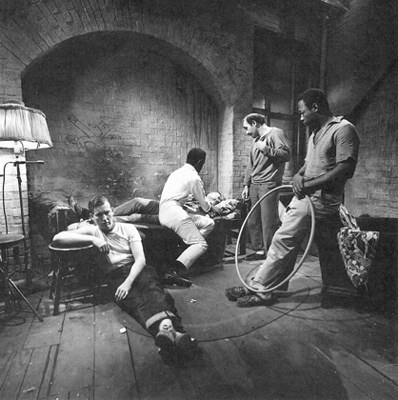

Vancouvers Pacific Cinémathèque is screening two classic avant-garde works by New York City filmmaker Shirley Clarke The Connection and Ornette: Made in America in newly restored 35mm prints this weekend.

The films are the first in a comprehensive project initiated by Milestone Films to restore and distribute the works of Clarke (1919-1997), a pioneer feminist filmmaker known for her experimentation with film and early video formats. Born into Park Avenue privilege, she lived out her life as the consummate Bohemian artist and for many years was a major hub of cinematic creativity in New York City from her apartment at the Chelsea Hotel.

Ross Lipman, senior film preservationist with the UCLA Film & Television Archive, talked to the North Shore News earlier this week about restoring both The Connection and Ornette: Made in America. In a separate interview producer Kathelin Gray discussed working with Clarke during the production of Ornette.

North Shore News: How did you become involved with the Shirley Clarke film project?

Ross Lipman: The Shirley Clark project developed over a number of years. We actually had material in our collection because Shirley used to teach at UCLA. We had a bunch of outtakes from The Connection and maybe an old print or two. We decided to pursue restoring it and at that time we were in dialogue with Lewis Allen Productions. Lewis Allen was a Broadway and film producer who she had worked with on The Connection. He was wonderful, as was his entire office, and we worked with them to get the original material. The story behind that is kind of interesting.

Normally when Im working on a project and someone wants to talk to me about it well talk about the technical and artistic challenges. But for The Connection the original negative had been stored at a laboratory for many years and they were going through some financial hardship. It was really difficult to get them to respond about shipping this material back. It took two years of emails from both myself and from Lewis Allens team, Sharon Fallon was his office manager. We were a tag team calling, pleading, to send over the material. We didnt even really know what it was at that time we thought it was a duplicate negative which is a negative that is further down its been printed from a copy. Each time you go down a copy with analogue film printing you lose quality. We were still hoping theyd have even that.

Finally, after two years of emails a box showed up at the archive. I opened the materials and lo and behold it was the original negative and it was mostly pristine condition, all except for one reel, so it was pictorially beautiful with this exquisite cinematography by Arthur Ornitz. The real battle on The Connection was an administrative struggle to get us the right material because when you say you want to preserve a film you have to preserve it from something and what youre preserving it from can be a major factor in the end result.

North Shore News: What was the timeline for that?

Ross Lipman: We actually preserved The Connection a long time ago in 2004. This preceded the Milestone project. It toured around and made a screen here and there but nothing on the level of what Milestone does on an international release. Then what happened is several years later Milestone started their project to work on all of Shirley Clarkes films. Weve always had a great relationship with Milestone, the archive has historically worked with them many times. In the interim UCLA had done a collaborative project with the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences preserving Robert Frost: A Lovers Quarrel with the World which is a lesser known but quite wonderful documentary that she did on the poet Robert Frost. Once Milestone worked out their arrangements with Shirley Clarkes estate, through her daughter Wendy, they came to us about working on Ornette: Made in America. So that was a truly collaborative project. The Connection and Robert Frost were collaborative projects as well. Its a perfect example of what I was talking about earlier because even though wed done the preservation work we hadnt done any digital work on those two titles so Milestone came in and spearheaded with our collaboration the digital remastering of both those films. So those projects became active again and reopened years later. For Ornette we ended up doing the digital work in advance of the preservation or at least in parallell to it.

North Shore News: Whats involved specifically on preserving the Shirley Clarke films?

Ross Lipman: Each one is different because she was such an experimenter. For The Connection, a large part of it was administrative in getting the original negative. Having said that theres several levels to that and its also an example of how the project continued on into the future. We worked with the existing laboratories to get as good as possible black and white printing of the original cinematography of the original restoration. You cant keep running print after print off that original negative. We had to then make a duplicate negative copy so that when youre running it through the printer all those times its not risking damage to the rare original. New film stocks are made on polyester which are stronger than the acetate material of the original 1961 film. But when youre going down to make that copy youre going to lose detail in analogue film printing. We worked very hard with FotoKem Laboratories to go through all sorts of tests to make sure we got the highest pictorial quality and retain that image information through the successive generations. If you look at the prints off the dupe negative theyre going to look really really nice. Theyre not going to look identical to prints off the original, thats impossible, but that was one of the real challenges testing and finding out how to manipulate the laboratory process and printing methods to retain the best quality of that negative which had a lot of detail. If you compare the prints that we made off our dupe negative compared to prints off the old dupe negative ours are much better.

Ornette: Made in America is a compilation of every kind of format imaginable from home movies to video to Super 16 theres everything in there. Theres so many things in there you need to retain the collage nature of it.

That was a challenge in itself but the thing that I think about when I think about Ornette was the soundtrack. The producer Kathelin (Hoffman) Gray did a great job of keeping all the original production materials however one item slipped through the cracks and Im not phrasing this as a criticism this is one of the things that happens: the original final master sound mix of the final film was lost probably in a laboratory closure because a lot of materials remain at the laboratories. So although we had all these outtakes and preliminary recordings nothing conformed to the final version and because the film is such a collage you cant go in putting little piece after little piece because those scraps arent clearly identified. When they were filming the Skies of America concert in Fort Worth there were all sorts of cameras and recording equipment to best get high quality sound of the performance but we have nothing that corresponds to what Shirley did in the film.

We had to work from the old analogue film prints and there we worked very closely with John Polito of Audio Mechanics, one of the best sound restoration labs in the country. We worked with these lower grade recordings but without distorting what was there worked to prize out the highest possible quality sound and the best audio fidelity of the musical performances that appear in the film. Im very pleased with the way that that turned out because we really managed to get a real full-bodied sound and so much of the film depends on the quality of the music and were really indebted to John Polito of Audio Mechanics for that.

North Shore News: How did you get involved in film restoration?

Ross Lipman: My background is both as a filmmaker and as an archivist. The films that I have been making for many years are experimental and in experimental film I trained in a lot of laboratory procedures that before digital used to be how you manipulate the image before digital tools were used. I have a background in both the technical aspects of film printing and processing but I also am interested in film history and began as a film researcher for documentary companies so my interest in film history and my experience in film production merged together and led me towards film preservation.

North Shore News: What expertise is involved in film preservation? It seems like a mix of art and science.

Ross Lipman: Exactly right. You really do need to have both a knowledge of film history, an understanding of those films roles in history but also the experience in how theyre made and how to then render those images in new copies. Because a lot of the work of film preservation, unlike art preservation where youre just conserving the original artifact, we do that but my work consists in essence of making new copies and when you make new copies you have to preserve both the content and the quality of the image and the sound. For example, a film may have been re-edited over the years by different distributors, it may have been recut, it may have been simply physically damaged and you need to find out what the film looked like and then make a new copy or version of it that is faithful in spirit, and hopefully in form, to the original.

North Shore News: Are there particular formats and genres that you personally work with more than others?

Ross Lipman: We work with anything but I tend to have a specialty with independent and art cinema but thats used kind of loosely. Ive done a lot of documentary work I consider all those documentaries art works in themselves. I worked on The Times of Harvey Milk and Emile de Antonios films. These are strong cultural and esthetic statements as well as social ones.In terms of formats, yes, we cover everything. We still tend to be focused on photochemical film reproduction because that is more archival.

There are all sorts of issues that come in when you try to put an analogue work into a digital format and leave it there. Thats what we would call digital remastering. You are taking something that was once analogue and making a digital copy and theres all sorts of reasons why thats not considered true preservation in the archival sense. We do it all the time but we just call it something different. What we do do in film restoration is use a digital intermediate. We will scan something and use digital tools to solve problems that can not be easily fixed with photochemical methods. Well remove dirt and reduce scratches, colour fading and things like that, then well take the digital file and output it back to film so you have an archival element that is truly preserved in the photochemical medium and also a digital work that has been integrated into that.

In the case of the Milestone titles well do all these things side by side because UCLA for example will focus on the photochemical restoration and archival aspects. Milestone will take care of the digital remastering (the archive does this sometimes on its own too Im just using the Clarke films here as an example) and well work together to make digital viewing copies as well as the photochemical ones and so theyll exist in multiple formats its just a question of what you call each of these things.

North Shore News: Doesnt that happen with everything nowadays?

Ross Lipman: Not everything. Everything is a broad term. We have a lot of projects at the archive that will only be photochemical. Usually these things are project-determined some projects have an immediate access to digital work others dont.

North Shore News: How do projects come to you? Do you initiate them or do they come to you?

Ross Lipman: In a variety of ways. A donor might approach the archive with a particular project they want us to work on. The archive might initiate a project and look for funding it really happens in a variety of different ways.

North Shore News: Youve been involved with a number of ongoing projects: Cassavetes, Kenneth Anger, Charles Burnett, John Sayles. Why Sayles? His films are fairly contemporary.

Ross Lipman: Its a misnomer to think that contemporary films don't need treatment. Just to give some modern examples The Times of Harvey Milk thats a 1984 film the magnetic soundtrack for that was already deteriorating, it was in really bad shape. Killer of Sheep, from 1977, the original negative had extreme vinegar syndrome. In films from the 1970s you can have colour fading, it depends on how theyve been stored, so very contemporary films can have all sorts of problems that need immediate attention.